The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us.

The Greek gods created a woman – Pandora. She was beautiful and charming and versed in the art of flattery. But the gods also gave her a box containing all the evils of the world. The heedless woman opened the box, and all evil was loosed upon us.

It’s often extraordinary the international platform that silent films afforded their stars. Pandora’s Box is one of the now lauded pinnacles of Weimar cinema and yet its main starlet — its acclaimed cover girl — was an American. With her bob hairstyle and vivacious sensuality, Lousie Brooks became synonymous with the Lulu character she portrayed in this film. It was this persona that caused her to rival other noteworthy contemporaries including Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo.

Except she differed in that Hollywood was not her first choice. Hollywood was not what made her a star. In fact, she shied away from that route, instead opting for other avenues altogether. That’s how she wound up partnering with director G.W. Pabst in not only Pandora’s Box but another classic, Diary of a Lost Girl. Then when she had enough she retired from the trade allowing her legacy to be championed by film aficionados years later.

The film in itself is really a bit of a parable taking inspiration from Greek mythology and sectioned off into Acts like a stage play. Pandora’s Box, is of course, the titular object that released all the evils into the world leaving only hope behind. The parallels are planted early on as Lulu lives life with a flirtatious vitality but that’s precisely what leaves a wake of destruction in her path. She woos every man who comes her way, a dancer and performer for all who will lend an eye. As of right now, she is the mistress of a well-to-do businessman named Schlon but he realizes that he needs to protect his image.

He plans to marry another woman but Lulu finds a way to unwittingly needle her way back into his life forcing his hand and ultimately winning him over again. But the conquests that come her way never last and she truly is a destructive temptress — a landmark femme fatale — she cannot help but flaunt her sexuality. She’s energetic, pernicious, meretricious.

The turning point of the film comes at Lulu’s trial sequence for the deed that she unwittingly perpetrated. The prosecutor stands over her wagging his finger as she’s veiled in somber shades of black. Her journey could end there but instead, she is granted another reprieve and escapes with two companions to London.

Not being bogged down by Production Codes of any kind, Pandora’s Box plays with some surprisingly frank themes most obvious of those being Lulu’s overt sexuality as well as adultery, prostitution, scandal, and so many other taboos. However, what makes the film quake with emotion is the very fact that Lulu is hardly an evil individual. Misled, immoral, and destructive yes, but it’s easy to feel sorry for her. Hers is the ultimate tragic narrative because while she assuredly ruins other people, she’s only injuring herself even more so. She dredges up so much hurt and elicits so much violence. All her attempts at love are only met with brutality.

Through it all, we follow faithfully even though we know from the outset it’s all for naught. And that’s a credit to Louise Brooks’s portrayal because there’s no doubt that she has that special something that makes you turn an eye and look. Her performance runs the gamut of emotions so uninhibited, lively, and free. There’s a universal vim and vigor to her that still feels fresh to this day in an otherwise archaic mode of filmmaking.

The amazing thing is that she probably could have been a bigger star than she actually was. She never really realized the potential that she had like a Dietrich or a Garbo but that’s not what she wanted. Still, the notability came her way anyways. Sadly, real life and the cinematic seem closer than you might expect. Her life was hardly as tragic as a film but you wonder if she ever found love chasing after men as she did.

4.5/5 Stars

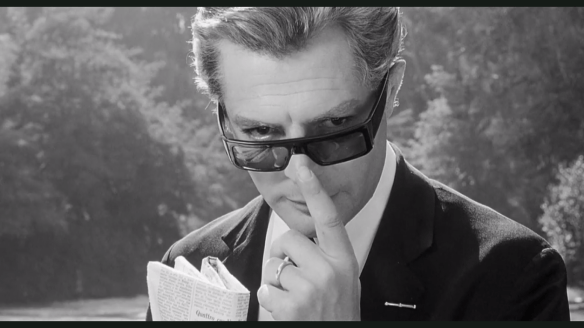

I never thought I’d get so fed up with hearing the name “Fefe.” But it’s true. There’s a first time for everything. In fact, Fefe is the name of our main character played so magnificently by Italian icon Marcello Mastroianni. In my very narrow view, he still very much epitomizes Italian cinema for me.

I never thought I’d get so fed up with hearing the name “Fefe.” But it’s true. There’s a first time for everything. In fact, Fefe is the name of our main character played so magnificently by Italian icon Marcello Mastroianni. In my very narrow view, he still very much epitomizes Italian cinema for me.

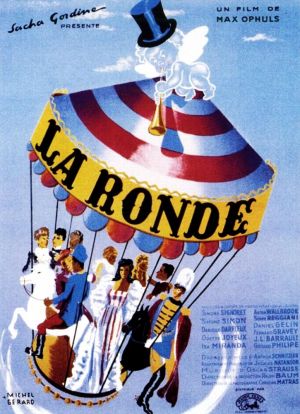

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly.

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly. The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.

The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in. Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too.

Watching films with French treasure Mr. Hulot (Jacques Tati) is a wonderful experience because, in some respects, it feels like he brings out the child in me. And if history is any indication — I’m not the only one — others feel this sensation too. “You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.