The scene is set. It’s a week before Christmas. We find ourselves in the charming community called Balboa, 50 miles from Los Angeles, and Joan Bennett drives off into the city for very urgent business. She meets an undesirable in a bar, but this is by no means a tryst. She is facing a sleazy opportunist named Ted Darby to forbid him from seeing her impressionable daughter.

In her opening actions, we already know so much about her. She is assertive and willing to go to great lengths to ensure the safety and protection of her family. Like Shadow of a Doubt before it, we start out in the symbolic sordidness of the city only to return back to the oasis by the sea. The Reckless Moment becomes another home noir where worlds clash.

Ironically Bennett has shed her femme fatale exterior and has come to watch over a household fending off the wiles of the world to keep them from entangling her children. She lives with her elderly father and a young son constantly badgering her while the family’s servant Sybil (Frances E. Williams) proves her most faithful ally. An affluent, hardworking husband is said to exist, nevertheless, he is never seen as he’s away on business in Germany.

For all intent and purposes, it’s Lucia Harper’s ship to run while her husband’s away, and she weathers quite the ordeal. Max Ophuls reacclimates his leading lady with her home, laying out his typical red carpet complete with a spiraling shot up the stairs.

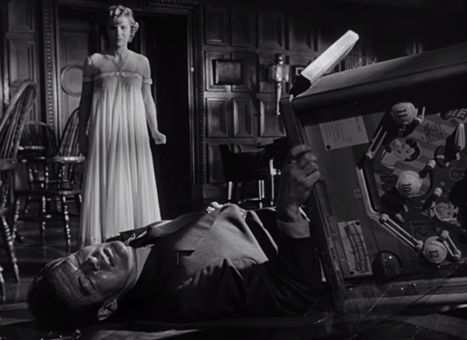

Her daughter Bee (Geraldine Brooks) starts out as a little terror though not quite capable of Ann Blyth’s treachery, because she sees the error in her ways. It comes to pass after her older suitor Darby pays a house call in the dead of night to rendezvous with the young girl. However, it is in the cloak of darkness the youth recognizes his true lecherous character, fighting to get away from him and fleeing the scene as he tumbles, ultimately, to his death.

He effectively disrupts their tranquility by diffusing from the urban center and breaching the sphere of domesticity ruled over by Lucia. The mother hen goes to great lengths to protect her daughter, even further implicating herself.

Because the next morning she finds the body, puts two and two together, and realizes she must do something. With nerves wrought of steel, she somehow manages to dispose of the body in order to protect her daughter. Of course, as we already know there was no need to, but it does make for an intriguing moral drama, and we have yet to even get a glimpse of James Mason.

He does finally arrive and once more, like Darby before him, he is yet another threat to Lucia, invading her drawing room unannounced. His price is $5,000 for some incriminating letters they have of the girls, which might easily implicate her with the police. For the woman of the house, you wonder if this nightmare will ever end because this is what noir always manages.

It takes this perfect post-war reverie and middle-class suburbia then injects it with something terrifying, even calamitous. But thankfully, with performers of the caliber of Bennett and Mason, we get a far more nuanced development.

These central roles are key because everything else revolves around them. They are two poles of the noir world who drag each other toward a murky center where she dips her toes into to the ugly underbelly and he, in turn, gains a coat of chivalry to redeem his moral character.

Because not only does this handsome crook begin to harbor sympathy for this woman — he even extends clemency to her — and as a result of their numerous interactions, he starts to fall in love.

It becomes an increasingly curious relationship because at first, it’s purely that of a helpless mark and the greedy profiteer. But as time passes, it gets ceaselessly complicated. With the husband out of the picture, and James Mason such a prominent star in his own right — it does feel like a secret tryst — a bit of a hidden love affair.

Except it never amounts to anything, because he covers for her, falling back into the dark depths of his old world, and she is able to sink back into hers. Our final image is of her, back turned to the camera, tears in her eyes, reassuring her husband everything is fine on the home front. The credits roll but I’m almost just as intrigued to know the aftermath of such a cataclysmic shift in her life.

Will her clandestine relationship with this man come to light and be seen through the sacrificial lens it probably deserves? Will she ever be able to share her dark secrets with her family and husband? Will the tranquil island getaway of Balboa ever be the same?

Yes, there are time restrictions to this story but the beauty is how much we still are invested in everything falling outside the frame. Here is a testament to an immersive film full of volatility and perplexing emotion that carries a certain weightiness.

It helps to have an intimate connect with this location. I even spent one summer during my youth working on Balboa Island and it is a sandy, relaxed, tourist trap. There’s no doubt about it. I can only imagine how much it would change if your memories of it were imprinted with something so ghastly.

Locals know the annual boat parade at Christmas. Of course, it takes on a different meaning with brawls in boathouses and dead bodies dredged up in the bay. At least it’s only a movie. Knock on wood…

4/5 Stars

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly.

If you know anything about director Max Ophuls you might realize his preoccupation with the cycling of time and storyline, even in visual terms. He initiates La Ronde with a lengthy opening shot that, of course, involves stairs (one of his trademarks), and the introduction of our narrative by a man who sees the world “in the round.” He brings our story to its proceedings, introducing us to the Vienna of 1900. It’s the age of the waltz and love is in the air — making its rounds. It’s meta in nature and a bit pretentious but do we mind this jaunt? Hardly.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.

It never feels flashy or superficial in these crucial moments. Any slick plot device or cinematic allusion falls away to get at the heart and soul of this film. It’s about coping with death and finding closure in that terrible event in life. Specifically for this one young man, but it is universally applicable to most every one of us. Especially when you’re young because as young, naive individuals, death can feel like such a foreign adversary. It’s so far removed from our sensibilities, and that’s what makes it so painfully unnatural when it strikes. In many ways, Greg is our surrogate. For all those who struggled to find themselves in high school, or college, or even life in general. And for all of those, who took risks on friendship in a world full of death and dying. Once more Me & Earl and the Dying Girl proved its worth, not by being a perfect film, but by being a heartfelt one.