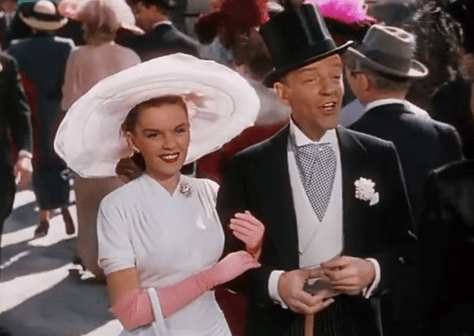

Some may recall the opening titles of Top Hat (1935). They play over a man’s hat only for the head under it to move as the names subside, and we find Fred Astaire under its brim in his coat and tails. Now, well nigh 20 years later, the same imagery is being called upon.

There’s an auction going on, including the sale of, of all things, a top hat evoking the same Astaire and Rogers musicals of old. It’s not in much demand as the man who formerly wore it, to much acclaim, is now a has-been. In fact, the biographical aspects of the picture are striking even when we can’t quite discern the fiction from the half-truths. Maybe that’s the key.

Already Fred Astaire himself had announced retirement several times, though one could hardly concede his career had stalled. In another bit of fitting parallelism, Adolph Green and Betty Comden penned a husband and wife duo for the storyline much like them (sans marriage). The head maestro character had some inspiration in Jose Ferrer who at the time had at least three shows on Broadway and was starring in a fourth.

The dashes of authenticity are all but undeniable as is a minor cameo by fawned-over heartthrob Ava Gardner. Consequently, I always thought the actress shared some minor resemblance to Cyd Charisse who was promoted to leading lady in this movie.

Out of these details blooms a picture that’s a fascinating exercise in touched-up reality because we see the ins and outs of a production with a behind-the-scenes narrative akin to Singin in the Rain. It makes us feel like we’re a part of something on an intimate level.

The early “Shoeshine” number with Astaire checking out a penny arcade, shows the inherent allure of a Minnelli-Astaire partnership. Because it was Astaire who made film dancing what it is, intent on capturing as much of the action in full-bodied, undisrupted takes. The focus was on the dancers, and there was an examination of their skill announcing unequivocally that there was nothing phony about them.

But as technology began to change and more complex camera setups became possible, this newfound capability was seen as an aid to the art rather than a detraction. Gene Kelly was of this thought as well. With the combination of sashaying forms and a dynamic camera, there was a greater capacity to capture the true energy that came out of dance. One could argue reality was lost, but some other emotional life force was gained.

And we see that here with Astaire grooving around past fortune-tellers and shooting galleries with the world tapping along with him. He and the real-life singing shoeshiner, Leroy Daniels, build an indisputable cadence through a momentary collaboration. It proves infectious. Minnelli who himself had a background in set design seems most fully in his element surrounded by extras, colors, and any amount of toys to move around and orchestrate.

When Jefferey Cordoba (Jack Buchanan) finally signs on to direct and joins this dream team, he brings an endearing brand of histrionics with him. At his most quotable, he says, “In my mind, there is no difference between the magic rhythms of Bill Shakespeare’s immortal verse and the magic rhythms of Bill Robinson’s immortal feet.”

“That’s Entertainment!” captures his pure enthusiasm for the industry, giving anyone free rein to tell a story, where the world and the stage overlap and as the Bard said, all the various individuals are merely players.

However, this show previously envisioned as a happy-go-lucky musical hit parade soon takes on a life of its own, morphing into a retelling of Faust. We see Tony Hunter stretching himself as an actor, something Astaire himself was probably uncomfortable with. Likewise, he’s equally nervous about starring with Gabrielle Gerard who is a rapidly rising talent, thanks to the controlling nature of her choreographer boyfriend (James Mitchell).

Aside from her skill, her height is also something that the veteran dancer is self-conscience about. He smokes incessantly. She never does. So they each bring their insecurities and nerves to the production, erupting in a series of miscommunications during their first encounter. Still, the show charges onward regardless.

Even as the production proves to be a trainwreck and opening night approaches, it is the joint realization that they’re both out of sorts helping Tony and Gaby right their relationship. They take a ride through the park and wind up in arguably their most integral dance together.

Because it says, with two bodies in motion, what every other picture that’s not a musical must do through romantic dialogue or meaningful action. And it’s like the Astaire and Rogers films of old. Similarly, dance is not simply a diversion — something pretty to look at — but it becomes the building blocks for our characters’ chemistry.

I find their forms marvelous together, both equally long and graceful side-by-side and in each other’s arms. The movements are so measured, effortless, and attuned, leading them right back into their carriage from whence they came.

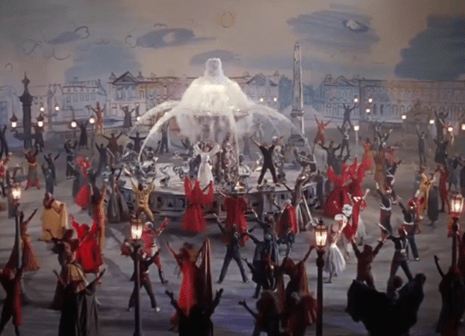

Cordoba gets progressively carried away with his vision in what feels like tinges of The Red Shoes. Pyrotechnics and an excessive amount of props mask the core assets of the show, which are the performers themselves. What was purported to be a surefire success, just as easily becomes a monumental flop as the social elites walk out of the preview like zombies leaving a wake. Even if the image is laughable, it also acts as a reminder that all great forms of entertainment start with human beings.

“I Love Louisa” is a kind of musical reprieve as the whole gang, from the stars to the bit performers, try to shake the shell shock. The fun is put back into the players, their art, and this whole movie as Tony resolves to take their production in a new direction — as a musical revue.

I couldn’t help watching Cyd Charisse, for some reason, during the song. No, she’s not the focal point, but there she is prancing about and having a merry old time with all the extras in the background. They’re all a community of people enjoying their failure together. Bonding over it. It’s bigger than one individual. It’s easy to acknowledge The Band Wagon might be thoroughly enjoyable for these periphery elements alone.

There are a couple, dare I say, throwaway placeholders to follow. Certainly, not the best of musical team Schwartz and Dietz. But “Girl Hunt — A Murder Mystery in Jazz,” is a labyrinthian sequence capturing the essence of the dark genre through voiceover and stylized visuals being interpreted through muscular dance. There are dual roles for Charisse as the deadly female. The action culminating in a seedy, smoke-filled cafe complete with a final showdown with a femme fatale in drop-dead red.

In this redressed form, they’re a stirring success. We are reminded sentimentally that the cast has become a family and Tony is their unlikely head. There’s one rousing reprise of “That’s Entertainment!” and Fred and Cyd (not Ginger, sorry folks) share a kiss.

The Band Wagon is a testament that Astaire was far from washed up and Charisse proves herself ably by his side as one of his best co-stars. What imprints itself, when the curtains have fallen on this backstage musical, is just how congenial it is. There are few better offerings from MGM, capable of both exuberance and something even more difficult to find these days: bona fide poise. Singin in the Rain is beloved by many and yet The Band Wagon is deserving of much the same repute, whether it’s won it already or not.

Just watch Astaire and Charisse together. Her beauty is surpassed only by her presence as a dancer. He might be 20 years older and yet never seems to break a sweat, pulling off each routine with astounding ease. Look at his elasticity in the shoeshine chair as living proof. And when they strut, extending their legs with concerted purpose, it’s immaculate. We call them routines but they are not, imbued instead with a gliding elegance that looks almost foreign to us today. There’s nothing else to be said. It’s pure class personified and they make it deeply enchanting.

4.5/5 Stars