“We’re not talking about eternal truth or absolute truth or ultimate truth! We’re talking about impermanent, transient, human truth! I don’t expect you people to be capable of truth! But, you’re at least capable of self-preservation! That’s good enough!” – Peter Finch as Howard Beale.

Throwing around the term auteur and you’ve already set yourself up for a grievous debate with some diehard cinephile. There are those ardent disciples as well as those who vehemently oppose what they deem a simplistic notion.

Because the main tenet is that the auteur or “author” who exacts his vision on a movie is namely the director. However, if there was ever a subject to cast in the role of “screenwriter as auteur,” Paddy Chayefsky just might be the perfect candidate. He came of age in the medium of television, an adamant humanist and purveyor of social realism. His most prominent work of those early years being the heart-warming classic Marty, which first starred Rod Steiger and then did great things for Ernest Borgnine in the film adaptation.

Network is conveyed by a veteran Chayefsky who has weathered the industry for a long spell now and looking at it presently, we observe his wry bit of commentary. Because the beast of a medium made him but he seems to derive some glee from confronting it head-on. He’s taken the systems in place and very conveniently added his own spin.

Along with the Big Three, CBS, NBC, ABC, he has created his own outlier, a dark horse, and the littlest giant UBS. The landscape is one familiar to anyone who lived through the 70s. Nixon got the can. There have been two recent attempts on President Ford’s life. It’s the wake of Watergate and Vietnam, with the throes of inflation and depression. America is looking for an escape valve for their dissatisfaction.

I’d like to think that the world of The Mary Tyler Moore Show has some semblance of truth to it with its camaraderie and the humanity of its comedy, but then we see Network and are provided another harsh alternative that bears the uneasy feeling of its own truth.

In this same world of civil unrest, television networks with their programming regimens and new shows are bloated with all sorts of agendas. You have the continually clashing horns between warring executives and self-serving angles in their neverending quest for higher ratings and a bigger share of the viewing public.

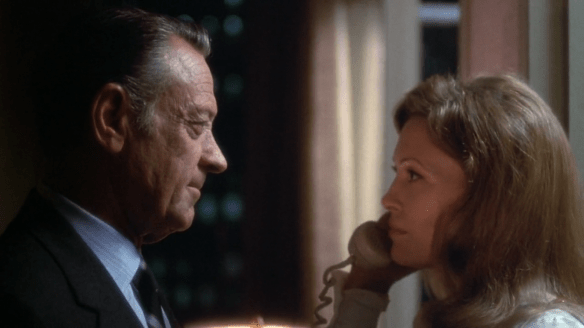

Max Schumacher (William Holden) is a remnant of television’s bygone era where men like Ed Murrow and Walter Cronkite were symbolic purveyors of truth in all facets of America. Maybe the nation was naive but at least they believed in something. Times have changed. Sensationalism and stories to stir up some form of controversy are of particular interest especially with Diana Christensen (Faye Dunaway) who aims to use such material to bolster the network’s abysmal ratings.

Meanwhile, abrasive big whig Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall) is tired of the news division’s lackluster performance, and he’s ready to instigate some new changes within the business conglomerate. Schumacher feels slighted as his former allies seem to crumble around him.

Now’s about a good time as any to introduce Howard Beale (Peter Finch). He’s one of Max’s best friends from the old days and due to plummeting ratings, he’s been given the axe. I never felt sorry for Howard Beale before because he’s so often lost in the shuffle of the movie. He’s used by not only the network but the film itself as a kind of diatribe. It seems like the man is all but forgotten.

Finch plays the role so pitifully at times and that becomes easily overshadowed by his attention-getting histrionics. However, when he makes his initial announcement that he will take his life on air, in two weeks’ time, it’s very matter-of-fact. There’s little agenda to it. Here’s a man who’s lost his wife and now is losing his job after 11 years of service to the network. Soon he’ll have nothing.

The utter disinterest in his plight is what’s most striking when you look down the line of producers and behind-the-scenes employees who sit in the dark in front of the monitors chatting rather than actually paying attention to their anchor. Apathy seems to reign.

Simultaneously, Christensen is exploding with harebrained schemes of inspired lunacy that she seems all too serious about enacting, from a docudrama called The Mao Tse-Tung Hour to keeping Howard Beale on the airwaves. She’s the foremost proponent of angry shows to articulate the angst of the general public through counterculture and anti-establishment programming. That’s her agenda.

In this very way, Network is a film of bewildering disillusionment in the world full of crises and absent of reason and maybe even God. Howard is a voice to all those absurdities and when he calls B.S., he turns the heads of the entire country. It blows up but as any publicity is good publicity, Diana convinces her boss to keep the mad prophet on.

She positions Howard Beale as a prescient even messianic figure calling out the hypocrisies of the age. Her boss openly objects, “We’re talking about putting a manifestly irresponsible man on television,” which Dunaway promptly nods her head in response to. Maybe she’s a bit crazy in her own right.

Then, when the fad keeps on going and he’s now got people yelling out their windows or sending their grievances straight to the White House, Christensen is complaining that he’s too irascible, not apocalyptic enough, recommending some writers be brought on to pen some juicy jeremiads for him to spout off. In spite of the ludicrous nature of it all, the results speak. Soon Howard Beale’s antics have landed him 4th in the Nielsen ratings surpassed only by The Six Million Dollar Man, All in The Family, and Phyllis.

Hackett is deliriously happy about the success and becomes power-hungry. But as Beale’s sole friend still kicking, Schumacher can’t help but feel Howard’s being used, even as he himself gets involved with Diana (she harbored a girlish crush on him in college).

The film’s trajectory seems all but predestined. The fad of Howard Beale begins to wane and ratings go down with him. Max Schumacher’s job and then his marriage go down the tubes as well, all because of Diana. For her part, Diana is so completely consumed by her work that everything, even her personal life, works in scripts. However, the rendition of The Blue Angel that she’s unwittingly been playing with Max doesn’t end as she initially thought.

As a satire of the medium we know as television, Network certainly has few equals. Chayefsky spends a good spell of time orating off his soapbox as he does in many of his pictures. The ideas are there. The words are coming from voices and we’re taking them in, and they are spiced up with rhetoric and wit. If anything, one can marvel at his work even when it doesn’t take. It bears his mark.

The one thing about Network that is still harrowing today is the mere implications. Television was being considered an institution systematically destroying everything it touched through its manipulation and backstabbing industry practices. It only exasperates the situation by breeding a public that’s both vacuous and apathetic.

There is no call for human decency anymore. There are no true glory days. People are depressed, lonely, bitter, and helpless. If that all came to pass, theoretically, because of a box sitting in a family’s living room, 21 inches in size, that could be turned off, and had bad reception more often than not, what is the internet doing to us?

Now we’re in constant interface with our devices, warring for our attention and promising us comfort and convenience. Meanwhile, our ghost machines suck us dry. We’re shells of human beings. There are some figures in Network that I dislike, played most convincingly by Duvall and Ned Beatty. They seem opportunistic, crass, and merciless. But most everyone else of note I feel somewhat sorry for. The Max Schumachers, the Diana Christensens, and of course the Howard Beales. What did we do to deserve this madness?

4/5 Stars