The French (and Europe in general) have unparalleled esteem for Jerry Lewis. It no doubt allows them to put him in conversations with their own beloved Jacques Tati as the true heirs to the Chaplins and the Keatons of comedy.

It’s no major revelation most Americans, flagged from the general populous, might scoff at such pronouncements. Because Jerry Lewis was just the comic with that obnoxious voice doing bits with Dean Martin and screwing around. This is my own bias acting out. He’s undoubtedly wildly popular with many.

Still, his type of comedies and routines feel like a dime a dozen. His most renowned picture, after all, is The Nutty Professor, and then his string of comedies with Martin, while successful, were never critically reputed.

What our friends across the pond take into account is how Lewis made himself into a holistic artist capable of many things — not simply performing. We saw this goofball. Whereas they rightfully recognized a visionary director, a prolific writer of material, who simultaneously helped to expand the language of film. It hardly seems like we’re talking about the same person, and yet we are.

What he manages to accomplish starts with taking comedy back to its purest roots, making it into a totally visual experience. There’s no better example than his stark departure with Frank Tashlin: The Bellboy. The Ladies Man builds off these ideas further, nevertheless, developing them with the same persona some adored since childhood and many, like me, will grow weary of after a couple of minutes.

However, this reaction easily clouds what Lewis is actually doing. He effectively turns the American Dream into a satirical, at times, surrealist fantasy playing upon his already solidified persona and allowing himself greater verisimilitude to explore ideas around the slapstick. At its core, The Ladies Man (with no apostrophe s) is an absurd tale of emasculation.

The inciting incident occurs in a small town where Herbert H. Heebert sees his best girl kissing a mostly unseen suitor following their junior college graduation. It’s a devastating blow. He takes this as a sign he must shrug off girls forever and try and find an occupation as far away from them as possible.

Of course, there’s then nowhere else for him to end up but a giant dollhouse full to the brim with attractive, young women of all shapes and sizes. It’s inevitable. Sure enough, Herbert is hired on by a housekeeper named Katie (Kathleen Freeman) who takes all his foibles in stride. Freeman is also one of the few characters who can stand up to the antics of her leading man. The indelible image occurs when he jumps into her arms out of fright. She’s there to be a foil emblematic of all things maternal and sunshiny.

Meanwhile, the introduction of the female tenants, unbeknownst to the slumbering Herbert, plays out as an intricate morning ritual complete with a jazzy accompaniment and of course, a whole host of alluring women.

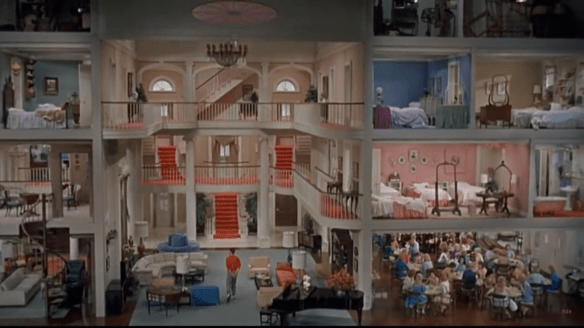

This is our first taste of the film’s obvious choreography, and it is executed on a grand scale. The dizzying set made up of rooms upon rooms, multiple stories, and spiral staircases is a veritable jungle gym for Lewis to play with. This pertains both to the actor and the director, realizing elaborate crane shots as his hapless hero is put up against this colorful, campy backdrop.

The glut of the film, by one means or another, follows his daily duties. Of course, they’re only an excuse for a range of gags. They involve a butterfly collection, passing out the mail, and being the in-house doorman. His most daunting task is taking care of “Baby.” One minute he’s sloshing milk through the living room in a bucket, the next minute dragging a huge slab of meat to feed the beast his breakfast.

Herbert has his own breakfast sloppily fed to him in a high chair by Katie. Yes, it’s strange. It is soon overshadowed by the film’s finest cameo by George Raft, who proves his authenticity to Herbert by showing off his dancing prowess — cheek-to-cheek.

The next extended aside is the picture’s most surreal moment when Herbert enters a “forbidden room” only to encounter a willowy woman suspended from the ceiling. He starts fleeing the slinking woman in black only for Harry James’s Orchestra and a dance floor to appear, facilitating their game of cat and mouse. Any meaning is oblique at best, but that makes it no less of a mesmerizing diversion. Afterward, things slip back into the status quo like nothing at all.

In the last act, the house gets invaded by a television crew and even more madness commences for Herbert as he is all but forgotten amid the tumult. Everyone is just happy he’s stayed around so long to keep up on their chores. It’s one girl named Fay (Pat Stanley) who actually has concerns for him as a fellow human being. This is rare.

In the dining room one morning, she decries her housemates’ manipulative behavior because they’re selfishly thinking about what they can say to keep him constantly doing their bidding. They have no concept of his thoughts or feelings, only his usefulness to them.

However, this indictment has telling implications. If this is a film about emasculation, what do we call the underappreciated place of traditional womanhood? How is this a critique of husbands and boyfriends who spend their evenings thinking of their significant others as nothing more than objects to cater to their whims?

It’s a toxic and quite damning scenario. While the ideal might be well-meaning it only stands up to scrutiny if both partners have symbiotic, multi-faceted roles meant to support one another. In other words, there needs to be some give-and-take, some form of interpersonal connection, and autonomy.

These observations alone make it necessary for me to eat my own words and my dismissal of Jerry Lewis. Because it’s initially difficult to acknowledge Lewis as an artisan and yet watching something like The Ladies Man, it’s impossible not to acknowledge its visual strengths. Yes, a lot of it’s not altogether funny, the gags are at times downright awful, and if you don’t relish Lewis’s own persona, you’re not going to be bucking for him to do his usual shtick.

But as a social commentary, there’s a surprisingly large pool of insights. Likewise, for its visual and physical feats, Ladies Man is a minor marvel even an extraordinary one, though it loses some weight thanks to all the mediocre elements.

Still, there are a handful of scenes with visual expressions and choreographies of a truly unique caliber. It’s as if in another life with a little touch-up, this might be the Marx Brothers mixed with Tati. Likewise, Tashlin’s own cartoon-like, visual wackiness has already been nodded to out of necessity.

Admittedly, my own greatest flaw is being an American. My impressions are already unflinching. When I look at Jerry Lewis I see a multi-talented performer who nevertheless, is more of a tiresome icon than a comic delight. To paraphrase a famous axiom, a comic is never appreciated in his own country. Thankfully, Jerry has the French (and everyone else). It’s the intellectual with the absurd: a match made in heaven.

3/5 Stars

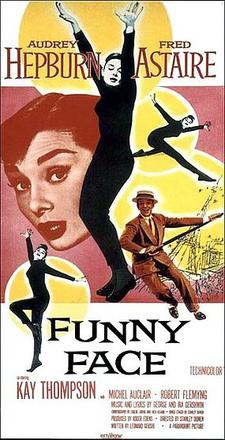

I’m not an expert on fashion photographers, but with only a passing interest in the industry, two of the most luminous names I know are probably Richard Avedon and Bob Willougby. Their names seem to crop up more than almost anyone when you consider film stills. It’s no coincidence that they both famously did shoots of Audrey Hepburn: one of the most widely photographed women of all time.

I’m not an expert on fashion photographers, but with only a passing interest in the industry, two of the most luminous names I know are probably Richard Avedon and Bob Willougby. Their names seem to crop up more than almost anyone when you consider film stills. It’s no coincidence that they both famously did shoots of Audrey Hepburn: one of the most widely photographed women of all time.