This is my entry in the Spring CMBA Blogathon Debuts and Last Hurrahs.

In the isolated occasions when I had to debate in high school classes those who did this kind of thing for fun and seemed most destined for politics, were all people I would never want to vote for regardless of affiliation.

In the isolated occasions when I had to debate in high school classes those who did this kind of thing for fun and seemed most destined for politics, were all people I would never want to vote for regardless of affiliation.

Because it seemed like there was a self-selecting bias. The people who wanted, nay desired, this kind of world, were not ones I necessarily respected.

How could a decent person of moral fiber get through and win? The cynical answer is they can’t unless they are propped up by a political apparatus of some kind. However, before I sound too jaded, I still am optimistic there are good people working in government.

No one would confuse John Ford’s The Last Hurrah for a tirade against big government and political machines. This is not a Frank Capra picture. Instead, there’s a certain level of give and take, a nuance, celebrating a style of old-fashioned politics while acknowledging the need for political strategy and networks.

No director brought more of the Irish-American experience to film than John Ford and you see it from his Calvary westerns to his West Point hagiographies, and even a portrait of his homeland like The Quiet Man.

Frank Skeffington (Spencer Tracy) is in the midst of his latest and perhaps final foray campaigning for the mayorship in a New England town. His personal entourage of right-hand men in bowler hats (including Pat O’Brien and James Gleason in his final role) have seen him through everything.

My initial observation is that this is a mature man’s game. The young (including myself) seem like idiots. His son (Arthur Walsh) isn’t registered to vote, doesn’t watch the debates, and is always running off after golf or other frivolous entertainments.

Another local magnate (Basil Rathbone) who opposes Skeffington has a son (O.Z. Whitehead) who makes a fool of himself by unwittingly accepting the position of local fire commissioner. Skeffington has instant leverage against his old adversary. Then, there’s an up-and-coming appointment — a young Catholic war hero and lawyer. More on him in a moment.

Skeffington is not naïve. He knows how to play the game. He’s continually pragmatic, pressing his advantages and the alliances at his disposal and knowing what it takes to win. You don’t maintain the office year after year without knowing the rules of the game. Perhaps Ford casts him with a rose-colored, nostalgic tinge, but at least he has some scruples or at least a sense of who his people and electorate are. Because he’s been knee-deep in the community.

His most obvious opponent is an unknown newcomer named McCluskey, and it becomes apparent he feels like a caricature cutout of John F. Kennedy if the man lacked charisma and intelligence.

Of course, JFK was a famously photogenic figurehead who used Frank Sinatra jingles, his public image, along with a platform to beat out Richard Nixon in 1960 (He also hailed from one of the most influential families of its day thanks in part to his father Joe Kennedy).

Nixon himself practically instigated the political television revolution with the pathos appeal of his Checkers speech in 1952, and thenceforward the televised debate presaged a radical new kind of American politics. The rules changed.

Adam Caulfield (Jeffrey Hunter), Skeffington’s nephew, works as a sportswriter at a local paper. His editor (John Carradine) fights tooth and nail against Skeffington with an obsessive grudge, throwing every iota he has behind McCluskey so he might vanquish his mortal enemy. Adam is far more accommodating and has a congenial relationship with his uncle.

When he pays the seasoned politician a visit, Skeffington calls politics the greatest spectator sport! He invites Adam to cover the events and tells him in confidence that he wants to try and win a campaign race one last time the old-fashioned way; he’s astute enough to know his days are numbered thanks to television and other readymade forms of advertising.

Although it’s not mentioned explicitly I can imagine Skeffington admired the political acumen and rhetorical vigor of a great American stalwart like Abraham Lincoln. John Ford of course made a whole film about his early years and rise to prominence before he ever became president.

I mention this only to echo the thoughts of Neil Postman in Amusing Ourselves to Death. Our culture shifted drastically from a literary culture where arguments were well-thought-out and expounded upon in debates hours long. And yet in the 1950s and 60s, we see this concurrent shift to a visual, image-based society.

Suddenly we watch campaigns being won and lost by optics, the most beautiful people, or those with the largest media share. It’s a far cry from the past and this is part that’s being memorialized. It’s a strange thing to be reminiscing about a world cataloged most comically in a movie like The Great McGinty, but there is something rather quaint about it compared to the juggernauts of media and consolidated power at work today on a global scale. It dwarfs anything out of the past by sheer scope and reach.

The whole film might easily be encapsulated by a few adjoining sequences. There’s a quiet scene with Anna Lee. Her husband Knocko has passed and left her little to nothing to subsist on. In an act of sheepish compassion at the kitchen table, Tracy offers her a sum of money on behalf of his dead wife. It feels like a pretense he’s made up, and yet here no one sees his kindness aside from the camera.

However, he sticks around for Knocko’s wake, and it becomes an extension of his political campaign. When word gets out, everyone seems to be coming by to pay their respects too, though it feels more like posturing. These moments can be humorous, darkly cynical, and still somehow have glimpses of communal warmth.

Taken on the whole, The Last Hurrah is a grand picture with a lot of cast, story, and ambition. But all that space gives Ford the opportunity to move around in and go to work with his gaze set on humanity. It’s the communal events or moments of ritual where Ford is at his finest: dances, weddings; here it’s a wake and a funeral.

I mentioned Capra before and his pictures, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington in particular, decry the mechanism of the political machine. However, the adapted novel and surely Ford as well had a prescience about them.

He somehow bridges a gap between Capra’s cinema, Sturges’s McGinty, and the emerging landscape. Because Elia Kazan in some ways would depict our certain future with A Face in the Crowd. It offered up a harsh critique focused on a country bumpkin turned charlatan who uses television to captivate the public and wield his newfound influence for political gain.

In such a climate the old guard like Skeffington can no longer exist. Part of this is the march of time. There are aspects of him that feel archaic and ugly with his back parlor dealings. And yet in the same breath, as we look at the vitriol that is shoveled today and the proliferation of social media, it does feel almost quaint. Again, this might be naivete speaking. We so quickly forget the political muckraking of prior centuries because we were not there.

I had to sit with this film, and the longer I was with it the more it moved me. Ford does what he does best by eulogizing someone he deems to be an everyday American hero. The flaws are laid bare and still, he can be lauded as a great man by all those he groused so bitterly with all through the years. On his deathbed, before he is about to be given the last rites, the local Cardinal (Donald Crisp) comes to ask his forgiveness. They have been at odds, bitter rivals, and yet, in the end, there is grace and mutual respect.

It feels like a beautiful testament, like a bygone sentiment we rarely see in politics today. Because Skeffington does signal the end of something — maybe it’s the classical statesman or something else.

Spencer Tracy lying on his deathbed is a picture of blissful contentment, and he has the feisty spirit of an Irishman to the end. The film has all the hallmarks of a swan song, but thankfully he and Ford still had so much to offer us respectively, and in their final years they continued to deliver some of their most rewarding work.

4/5 Stars

The opening images of Seven Days in May could have easily been pulled out of the headlines. A silent protest continues outside the White House gates with hosts of signs decrying the incumbent president or at the very least the state of his America. We don’t quite know his egregious act although it’s made evident soon enough.

The opening images of Seven Days in May could have easily been pulled out of the headlines. A silent protest continues outside the White House gates with hosts of signs decrying the incumbent president or at the very least the state of his America. We don’t quite know his egregious act although it’s made evident soon enough.

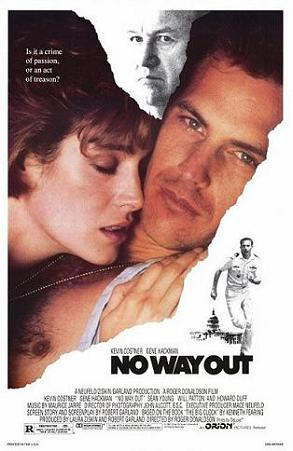

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists.

In the 1970s political paranoia involved issues in the realm of Watergate. Government conspiracy and that type of thing perfectly embodied by some of Alan Pakula’s best films. But it’s important to realize in order to better understand this particular thriller, the 1980s were a decade fraught with fears of Soviet infiltration compromising our national security. The Cold War was still a part of the public consciousness even after being a part of life for such a long time already. So No Way Out has a bit of Pakula’s apprehension in government and maybe even a bit of the showmanship of Psycho with some truly jarring twists. The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself.

The opening credits roll and recognition comes with each name that pops on the screen. Jean Arthur, James Stewart, Claude Rains, Edward Arnold, Guy Kibbee, Thomas Mitchell, Eugene Palette, Beulah Bondi, H.B. Warner, Harry Carey, Porter Hall, Charles Lane, William Demarest, Jack Carson, and of course, Frank Capra himself. Its title suggests that this film might be something like Lubitsch’s Heaven can Wait but The Devil and Miss Jones could easily hold the title as the original version of Undercover Boss. Although its main function is on the romantic and comic planes, it also has a bit of a social message behind it that signals for change.

Its title suggests that this film might be something like Lubitsch’s Heaven can Wait but The Devil and Miss Jones could easily hold the title as the original version of Undercover Boss. Although its main function is on the romantic and comic planes, it also has a bit of a social message behind it that signals for change. With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft.

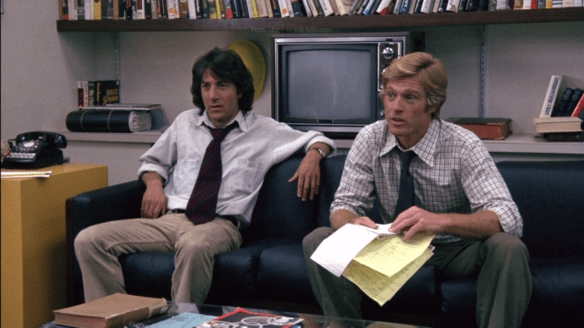

With Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon making a splash just the year before and giving a big leg up to its star Humphrey Bogart as well as its director John Huston, it’s no surprise that another such film would be in the works to capitalize on the success. This time it was based on Hammett’s novel The Glass Key and it would actually be a remake of a previous film from the 30s starring George Raft. You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams.

You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams. But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces.

But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces. Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact.

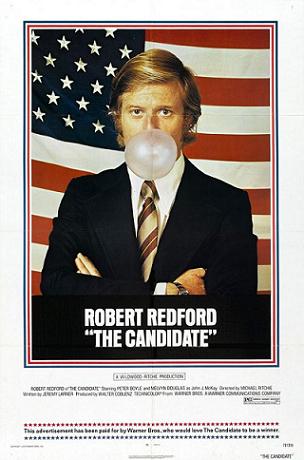

Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact. Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people.

Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people. This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either.

This is an Otto Preminger film about politics. That should send off fireworks because such a divisive topic is only going to get more controversial with a man such as Preminger at the helm — a man known for his various run-ins with the Production Code. All that can be said is that he didn’t disappoint this time either.