I love the forum that is created in international cinema where all things can be debated and discussed without fear of what the audience will say. Hollywood caters to the audience and that more often than not means that thrills are given greater weight than substance. Eric Rohmer worked at Cahiers du Cinema alongside French New Wave visionaries like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, but he joined the game a little later than his colleagues with a different style. Rohmer took his pseudonym from director Erich von Stroheim and British novelist Sax Rohmer. He was a highly educated man and that comes out in his films.

I love the forum that is created in international cinema where all things can be debated and discussed without fear of what the audience will say. Hollywood caters to the audience and that more often than not means that thrills are given greater weight than substance. Eric Rohmer worked at Cahiers du Cinema alongside French New Wave visionaries like Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut, but he joined the game a little later than his colleagues with a different style. Rohmer took his pseudonym from director Erich von Stroheim and British novelist Sax Rohmer. He was a highly educated man and that comes out in his films.

My Night at Maud’s comes from the perspective of a man, who we have a sneaking suspicion might be a lot like Rohmer. Jean-Louis (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is a reserved, highly religious, intelligent man. He attends mass on Sunday, bumps into an old school chum on the street, and willfully enters a discussion on all sorts of philosophical topics.

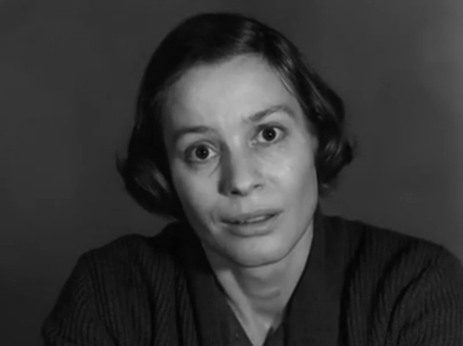

Whereas Godard interest himself in the lowly gangsters, the streetwalkers, or the lovers on the run, Rohmer’s character are in a completely different stratosphere. They are a higher slice of society, and it shows in what they spend there time philosophizing about. In fact, there’s a lot of discussion stemming from Pascal’s wager on whether or not it is beneficial to believe in God. Although he can be a bit of a clown, Vidal is also a philosophy professor and ready and willing to delve into such topics. He holds hypotheses on the meaning of life, and he’s considered where hope comes from. These are intelligent beings and deep thinkers, and by transference, they lead us to think. They drop by on Vidal’s friend Maud (Francoise Fabian), who is a divorcee, irreligious, and most certainly a free thinker. She’s also beautiful, and she likens there little late night convo to the salons of old as they gather around her bed to raise their conjectures.

I feel like I have known people like Jean-Louis, and I cannot help but like them. He’s a fairly resilient Christian, but not a perfect example mind you, and yet he feels far from a hypocrite. With his new dialogue partners, he speaks of his past love affairs and how they can exist with his religious convictions. Maud rather matter-of-factly labels him a “shame-faced Christian” and a “shame-faced Don Juan,” because he’s not fully committed or acknowledging of either. And yet she generally likes him a lot. He likes her company too and so they can continue talking in a genial manner. She pokes fun and ribs but never attacks. And she openly brings up numerous different ideas about Christianity. There are things that feel very human, but not very Christian to her. Maud asks if Christians are judged by their deeds? She assumes there is a bookkeeping aspect of Christianity where good deeds are weighted versus sin. Several times the rather obscure term of Jansenism is thrown around a bit in reference to the theology of Dutchman Cornelius Jansen. It surely is difficult to keep up we these folks at times, but it’s well worth it.

I feel like I have known people like Jean-Louis, and I cannot help but like them. He’s a fairly resilient Christian, but not a perfect example mind you, and yet he feels far from a hypocrite. With his new dialogue partners, he speaks of his past love affairs and how they can exist with his religious convictions. Maud rather matter-of-factly labels him a “shame-faced Christian” and a “shame-faced Don Juan,” because he’s not fully committed or acknowledging of either. And yet she generally likes him a lot. He likes her company too and so they can continue talking in a genial manner. She pokes fun and ribs but never attacks. And she openly brings up numerous different ideas about Christianity. There are things that feel very human, but not very Christian to her. Maud asks if Christians are judged by their deeds? She assumes there is a bookkeeping aspect of Christianity where good deeds are weighted versus sin. Several times the rather obscure term of Jansenism is thrown around a bit in reference to the theology of Dutchman Cornelius Jansen. It surely is difficult to keep up we these folks at times, but it’s well worth it.

Maud has her own preconceived notions about religion, while Jean-Louis has some delusions about romance. He thinks he’ll meet a pretty blonde Catholic gal and fall in love. It sounds utterly preposterous and yet then he meets Francoise (Marie-Christine Barrault) after his night at Maud’s. She’s the perfect embodiment of everything he’s ever dreamed of in a romantic partner. They seem like a good pair, although she is still in school, they are intellectual equals with similar personal convictions.

Sure enough, 5 years down the line they are married with a young son. Jean-Louis has not seen Maud for many years now, but quite by chance they bump into each other on the beach. Both pick up where they left off as if no time has passed because it’s so easy for them to converse. Francoise is noticeably uncomfortable around Maud, but nothing more is said about it. Jean-Louis moves on and plays contentedly with his family on the beach. Maud heads back up the hill as cordial as ever. This is an ending that is made powerful in its subtleties above all else because Jean-Louis and the audience realize something about Francoise. Yet there is no need to voice those conclusions because all that matters to him is that he is happy. It toes a soft line between romance and drama, instead resorting to a beautiful exchange of ideas. Noticeably, in Rohmer’s film, there is no score so the dialogue is elevated to the level of music. It fills the void using deep, introspective and personal forms of verbal expression.

Sure enough, 5 years down the line they are married with a young son. Jean-Louis has not seen Maud for many years now, but quite by chance they bump into each other on the beach. Both pick up where they left off as if no time has passed because it’s so easy for them to converse. Francoise is noticeably uncomfortable around Maud, but nothing more is said about it. Jean-Louis moves on and plays contentedly with his family on the beach. Maud heads back up the hill as cordial as ever. This is an ending that is made powerful in its subtleties above all else because Jean-Louis and the audience realize something about Francoise. Yet there is no need to voice those conclusions because all that matters to him is that he is happy. It toes a soft line between romance and drama, instead resorting to a beautiful exchange of ideas. Noticeably, in Rohmer’s film, there is no score so the dialogue is elevated to the level of music. It fills the void using deep, introspective and personal forms of verbal expression.

4/5 Stars

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century.

His ambitious follow-up to The Birth of the Nation a year before, D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance boasts four narrative threads meant to intertwine in a story of grand design. Transcending time, eras, and cultures, this monumental undertaking grabs hold of some of the cataclysmic markers of world history. They include the fall of Babylon, the life, ministry, and crucifixion of Christ, along with the persecution of the Huguenots in France circa the 16th century. “They say it’s just physical abuse but it’s more than that, this was spiritual abuse.”

“They say it’s just physical abuse but it’s more than that, this was spiritual abuse.”

“Now there are just two of us – young Aubrey Montague and myself – who can close our eyes and remember those few young men with hope in our hearts and wings on our heels.” ~ Lord Lindsay

“Now there are just two of us – young Aubrey Montague and myself – who can close our eyes and remember those few young men with hope in our hearts and wings on our heels.” ~ Lord Lindsay Back in the 1920s, a brash young Abrahams (Ben Cross) is about to enter university at Cambridge intent on becoming the greatest runner in the world, and taking on all the naysayers and discrimination head-on. He’s a Jew and faces the antisemitism thrown his way with defiance and a bit of arrogance. He’s a proud young man who loves to run, but more than that he loves to win. His best friend becomes Aubrey, a good-natured chap, who willingly lends a listening ear to all of Harold’s discontent. Soon enough Abraham’s makes a name for himself by breaking a longstanding record of 700 years, at the same time gaining a friend in the sprightly Lord Lindsay. Together the trio hopes to realize their dreams of running for their country in the Paris games of 1924. They are the generation after the Great War and with them rise the hopes and dreams of all those who came before them.

Back in the 1920s, a brash young Abrahams (Ben Cross) is about to enter university at Cambridge intent on becoming the greatest runner in the world, and taking on all the naysayers and discrimination head-on. He’s a Jew and faces the antisemitism thrown his way with defiance and a bit of arrogance. He’s a proud young man who loves to run, but more than that he loves to win. His best friend becomes Aubrey, a good-natured chap, who willingly lends a listening ear to all of Harold’s discontent. Soon enough Abraham’s makes a name for himself by breaking a longstanding record of 700 years, at the same time gaining a friend in the sprightly Lord Lindsay. Together the trio hopes to realize their dreams of running for their country in the Paris games of 1924. They are the generation after the Great War and with them rise the hopes and dreams of all those who came before them. Simultaneously we are introduced to Eric Liddell (Ian Charleston) a man from a very different walk of life. He’s a Scot through and through, although he grew up in China, the son of devout Christian missionaries. Everything in his life is for the glory of God, and he is a gifted runner, but in his eyes, it’s simply a gift from God (I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure). His sister is worried about his preoccupation with this seemingly frivolous pastime, but Eric sees a chance at the Olympics as a bigger platform – a platform to use his God-given talent to glorify his maker while living out his faith. Abrahams is a disciplined competitor and he goes so far as to bring on respected coach Sam Mussabini (Ian Holm) to help his chances. Liddell is a pure thoroughbred with life pulsing through his veins, and of course, they must face off. It’s inevitable.

Simultaneously we are introduced to Eric Liddell (Ian Charleston) a man from a very different walk of life. He’s a Scot through and through, although he grew up in China, the son of devout Christian missionaries. Everything in his life is for the glory of God, and he is a gifted runner, but in his eyes, it’s simply a gift from God (I believe God made me for a purpose, but he also made me fast. And when I run I feel His pleasure). His sister is worried about his preoccupation with this seemingly frivolous pastime, but Eric sees a chance at the Olympics as a bigger platform – a platform to use his God-given talent to glorify his maker while living out his faith. Abrahams is a disciplined competitor and he goes so far as to bring on respected coach Sam Mussabini (Ian Holm) to help his chances. Liddell is a pure thoroughbred with life pulsing through his veins, and of course, they must face off. It’s inevitable.