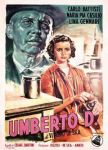

The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.

The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.

Vittorio De Sica’s film is unequivocally emblematic of the neorealist movement.The most notable traits are the images taken straight off the streets of Rome, depressed and forlorn as they are. The setting truly does act as another character, adding a depth to the film that cannot be fabricated. You can’t fake some of these scenes either whether it’s Antonio scavenging for his bike in the pouring rain or the sheer mass of humanity that is found in places like the Piazza Vittorio.

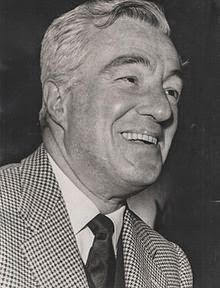

It’s all there out in the open, with an apparent authenticity. In its simplicity, it feels like a real story with real people. This too is aided by De Sica casting non-actors in the main roles. In fact, Lamberto Maggiorani’s gaunt face is somewhat unremarkable (sharing some resemblance to Robert Duvall). Put him next to a poster of Rita Hayworth and it becomes even more evident. Still, he too feels human in a way that Hollywood stars just cannot quite pull off. It’s easy to believe him and invest in his story.

The same goes for his young son Bruno. He’s one of the cutest precocious kids you’ve ever seen, reminiscent of Jackie Coogan in Chaplin’s The Kid. But it’s also his point of view that makes this film even more tragic later on. This father-son relationship has weight to it.

And that makes Antonio’s dilemma that much more perturbing and ultimately so traumatic for the audience. De Sica’s film is so humble and yet its depths are ripe with so many universal truths and moments of sincerity.

Here is a man trying to provide for his family. His wife, his son, and his baby. Work is hard to come by in the post-war years. Any opportunity is a good one and Antonio gets that. But he needs a bike. His wife sacrifices her sheets so he can get his bike — so he can maintain their whole livelihood as a family.

That’s why it’s so crushing. Everything hangs in the balance of this unfortunate but seemingly mundane event. When Antonio’s bike is stolen it truly means tragedy because there is no lifeline, no direction to turn.

And he does his best to recover his stolen property. Going to the authorities, rounding up his friends to search for it, even tracking down the boy who undoubtedly nicked his bike, but none of it leads to a successful conclusion.

Another day finished with no hope for tomorrow, no money to bring home to his family so they can eat and live. He’s got nothing — a reality that’s made painfully obvious when he and Bruno sit down for dinner at a restaurant. They eat a meager meal as those just behind them gorge on a full buffet of courses. Bruno eyes them longingly and his father tries to lift his spirits, secretly knowing that he can never offer that to his boy.

It puts his lot into a jarring perspective, suggesting the state of the affairs in Italy. But what makes the Bicycle Thief truly timeless is not its scope or what it says on a grand, majestic scale. It’s an intimate film and perhaps the most personal story ever put to film. In a matter of a few moments, it says more with the moral dilemma of Antonio than many lesser films conjure up in a couple hours.

And because this is not a Classical Hollywood film, it does not sell out to its audience. There is no obligation to the viewer to keep them from being downtrodden — because that might rub them the wrong way and actually evoke a searing response. But there can be beauty in that and De Sica’s film is certainly beautiful for precisely those reasons.

It feels real, it feels honest, and rather than sugar coating the world, it draws up a reality that is almost as old as the world itself. So yes, this film is so-called “Neorealist” and yes, it most certainly makes good use of its contemporary setting of Rome in the 1940s. But if any film can claim timelessness Bicycle Thief might just be the best bet because at its core are the type of issues that are not unique to time, space, language, or any other man-made barrier. Every person knows what it means to steal — to battle with their conscience — upending the moral framework that guides their lives. That hasn’t changed even if the context has and that makes The Bicycle Thief continually relevant.

It ambushes us with the same emotional wallop each and every time. I mentioned Chaplin before briefly, but it didn’t occur to me until some time later that we leave our characters walking off into the sunset rather like Chaplin’s Little Tramp, except it’s a very sad sunset indeed.

5/5 Stars