To set the scene our storytellers enlist an opening crawl that runs over the unmistakable strains of train noise. The year is 1861. The event being dramatized is the alleged Baltimore Plot and our hero is New York policeman John Kennedy (Dick Powell).

Despite being common and coincidental I can’t but help to acknowledge the bitter irony of our protagonist’s name. But he is not here to thwart a plot against his own life but a man with a much longer shadow.

His in-depth report warning against an impending threat to Abraham Lincoln on the road to his inauguration in Baltimore is dismissed by his superior as alarmist drivel. Nevertheless, the man finagles a way onto the Baltimore-bound steam engine finding an agreeable ally in Colonel Caleb Jeffers (Adolph Menjou). Kennedy once guarded Lincoln for 48 hours and yet in this perilous hour, he will go great lengths for the same man. However, we will soon find out that not everyone feels that way. He’s a very polarizing figure.

I’ve come to the not so startling conclusion that anything Mann touches turns into noir which I readily agree too. Much like Reign of Terror (1948) before it, the director transforms this antebellum train thriller into a reconstruction of history painted in tight angles, smoke & shadows, and coiled with taut action. We grow embroiled in his composed world of greasy close-quartered combat with grimacing faces and flying fists. Far from being constricting these elements are where the story thrives, trapped in corridors and hidden away in side-compartments with the characters that dwell therein.

Because moving through such a space forces Kennedy to brush up against so many individuals. A conductor (soon-to-be blacklisted Will Geer) who is trying to make sure everything goes as smoothly as possible only to be inundated by troublemakers and drama. A young mother (Barbara Billingsley) who tries to control her antsy son. An incessant windbag constantly worrying about her prized “jottings” and all she’s going to inquire to Mr. Lincoln about. A southern gentleman sounding off in his dismay with the countries future. You get the idea.

Despite the vague difference in context, it’s quite understandable to place The Tall Target up against another film from the following year The Narrow Margin (1952). Rather than try and decide which one is superior, it’s safe to say that both excel far beyond what their budgets might have you suppose and they utilize the continual motion of a train to an immense degree because in that way the narrative is almost always chugging along to a certain end.

Ruby Dee has a meager but crucial part in The Tall Target that I deeply wish could have been more substantial. In fact, in an early version, the established star Lena Horne was supposed to play the part of the slave girl Rachel.

Though the movie doesn’t have too much time to tackle the issues at hand, with its limited runtime it does attempt some discussion in terms of African-American freedoms and the southern relationship to such an ideal as asserted in the 13th amendment. The dichotomy I’ve always heard repeated is that “the North loved the race but hated the individual. Southerners hated the race, but love the individual.” It’s a vexing sentiment that we somehow can see playing out here.

Ginny Beaufort (Paula Raymond) a proper southern belle notes that she grew up so close to Rachel treating her like a sister. So close in fact that she never even thought about giving the young woman her freedom. Meanwhile, her younger brother Lance is involved in more than he is letting on. The mystery is not in his objective — he’s made his sentiments fairly clear — he despises Lincoln. Rather what matters is who his compatriots are and how they plan to go after the future president.

For me, the illusion was broken in the final moments because up until that time the picture has kept its eponymous hero masked. He is the Tall Target and nothing else. When we see him somehow the mythos around him is broken and he becomes another actor more than the idea of the man we know as our 16th president.

Regardless, Anthony Mann’s effort, while not well received in its day, is another picture packed with exuberance. It gives us grit and intrigue aboard a train and like the best thrillers, it uses every restriction to keep the tension palpable while throwing around enough diversions to keep us in our seats.

3.5/5 Stars

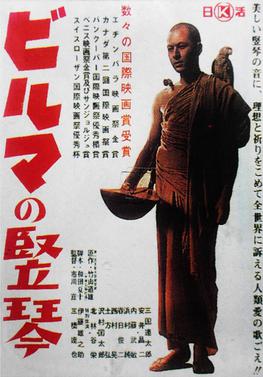

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.