Few films can please the restless masses that inevitably gather at some unfortunate souls home for a movie night. Because as varied and diverse individuals of a myriad of backgrounds we very rarely agree on anything especially given the proliferation of content that is available to us at any given time. But most can agree on one thing. The Princess Bride is one of the great crowd pleasers of its generation and for good reason.

If quotability was the sole parameter for a great movie then The Princess Bride has few equals and it also happens to be the most fun you’ll have in a single sitting because all that it does, it does with an unquenchable zeal. There’s a spirit to the film full of romance and humor and adventure, even playing to those who will forever be skeptical.

Adapted from his own novel, the venerable William Goldman carries over his framing device of a grandfather reading to his sick grandson and it works marvels to bring us into this tale. Especially when the two actors in question are a precocious Fred Savage (Pre-Wonder Years) and the inimitable Peter Falk (Post-Columbo) slipping seamlessly into the role of a grandpa with a twinkle in his eye.

The story unravels like many great fables with a love story torn asunder by circumstance. A young man who goes off to seek his fortune only to die (or more likely take on the identity of the Dread Pirate Roberts) and a young maiden who is made a princess and remains unhappy all the same without her true love. Of course, she does not understand the nefarious intentions of her soon to be husband Humperdinck nor that her love is going to great lengths to find her. And amidst the fantasy, swordplay, trickery, and rampant humor, love conquers all as it has a habit of doing in fairy tales with everyone of note living happily ever after.

This unabashed tale also boasts near pitch-perfect casting. Cary Elwes as Westley does embody a certain quietly confident charm that while not quite Flynn or Fairbanks still manages to guide the film with similar charisma. He can be the hero, handsome and witty, made to play perfectly off all the intriguing figures who inhabit this fairy tale.

In her debut, Robin Wright glows with a radiant beauty and stubborn defiance that’ s enduring and which in many ways has remained a defining moment in her career and it’s certainly not a bad film to be forever remembered for. Meanwhile, Mandy Patinkin plays the vengeful Spaniard Inigo Montoya with the perfect amount of bravado, honor, and charm in his lifelong search for the six-fingered man who killed his beloved father. He’s the perfect accompaniment for Andre the Giant’s lovable brand of brawn and Wallace Shawn’s hilariously irritating turn as their cackling leader.

But what makes the film even better or the odd sorts who pop up here and there including Miracle Max (Billy Crystal) a curmudgeon wisecracker like no other and The Impressive Clergyman (played by the oft-underrated Peter Cook) who single-handedly ruined the solemnity of wedding vows for all eternity.

Rob Reiner is rarely considered a masterful director but if anything it’s easy to make the case that The Princess Bride remains years later his greatest achievement because it has so much life provided indubitably by Goldman’s superlative script and the very figures who dare to fill his world. And Reiner captures it all with a clarity that comprehends the humor but very rarely goes for that at the expense of characters or story (unless they are villains or Billy Crystal). After all, this isn’t a Mel Brooks film.

By this point, it’s a disservice to call The Princess Bride a parody or mere homage– simply a cult classic that’s garnered widespread affection. The reason people love this film is connected to those aspects but also the very fact it stands on its own.

As Falk sings the praises of the story early on, so we can affirm, it has “Fencing, fighting, torture, revenge, giants, monsters, chases, escapes, true love, miracles…” If that’s not exciting nothing is and it’s quite easy to forget that the film is continuously hilarious but there’s something remarkably moving about its story. It plays the comedy well but simultaneously builds its own road through the mythology and fantasy of fairy tales that have captivated all people for eons.

In The Princess Bride, there’s not simply roots in comedies like The Court Jester but swashbucklers like The Adventures of Robin Hood or the magical journeying of the Wizard of Oz. It covers the spectrum of entertainment which is part of the reason it’s so satisfying.

It has scenes, moments, lines, those little idiosyncrasies and quirks that have left an indelible mark on viewers and as a result our culture as a whole. Lines like “As you wish,” “INCONCEIVABLE,” or best yet, “My Name is Inigo Montoya, you killed my father. Prepare to die.” Each has its special place within the context of the film and is still imbued with that same meaning hours after.

If I write about this film more from my heart than my head you’ll have to forgive but it truly is a weakness. I can envision being little Fred Savage enchanted by the sheer magic of fairy tales. I wouldn’t begin to care about romance until years later but swashbuckling and humor always had me enthralled and they continue to capture my imagination to this day–no more powerfully than in The Princess Bride. It’s sheer magic in all the best ways.

5/5 Stars

The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed.

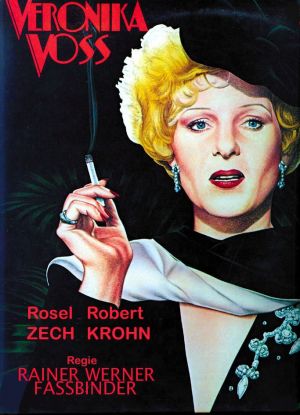

The last time I saw Hoosiers it was on VHS and I was only a boy and I hardly remember anything. Gene Hackman yelling. Dennis Hopper as a drunk. Jimmy the boy wonder, “The Picket Fence”, and of course Indiana basketball at its finest. But in those opening moments, as he drives into town and walks through the halls of his new home, I realized just how much I miss Gene Hackman. Yes, he’s still with us but the moment he decided to step out of the limelight and retire from his illustrious career as an actor, films got a little less exciting. His passionate often fiery charisma is dearly missed. You get a sense that if they had ever met, Norma Desmond and Veronika Voss might have been good friends. Either that or they would have hated each other’s guts. And the reason for that is quite clear. They share so many similarities. Both are fading stars, prima donnas, who used to be big shots and now not so much and that seems to scare them so much so that they try and cover their insecurities with delusions of grandeur. Having to look at your near reflection would be utterly unnerving.

You get a sense that if they had ever met, Norma Desmond and Veronika Voss might have been good friends. Either that or they would have hated each other’s guts. And the reason for that is quite clear. They share so many similarities. Both are fading stars, prima donnas, who used to be big shots and now not so much and that seems to scare them so much so that they try and cover their insecurities with delusions of grandeur. Having to look at your near reflection would be utterly unnerving.

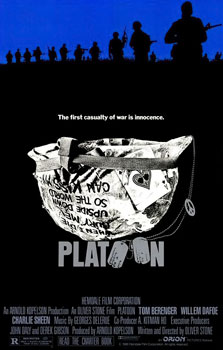

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

Why do you watch me? -Magda

Why do you watch me? -Magda And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can.

And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can. However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love.

However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love. Lou Gossett Jr. What a performance. He imprints himself on our brains just like the new recruits he berates, pushes, and toughens on a daily basis. He’s inscrutable. We want to hate him. We want him to get his comeuppance. Yet in the end, we cannot help but appreciate him. We are just like one of his recruits and that’s, in part, why this story works at all.

Lou Gossett Jr. What a performance. He imprints himself on our brains just like the new recruits he berates, pushes, and toughens on a daily basis. He’s inscrutable. We want to hate him. We want him to get his comeuppance. Yet in the end, we cannot help but appreciate him. We are just like one of his recruits and that’s, in part, why this story works at all. Watching An Officer and a Gentleman, it is rather amazing that it succeeds as part romance, part war drama since all its action takes place at an air force cadet school. They haven’t even reached the front yet. There are no explosions or bombs bursting in air. It even shares similarities with Fred Zinneman’s star-studded From Here to Eternity (1953) years before. But that story had far more star power and a climatic event like Pearl Harbor to build the story around. Here there’s nothing quite like that. But it’s not really needed. We are reminded that mankind is inherently interesting and when you throw a bunch of them together under duress it’s a formula for heightened emotions.

Watching An Officer and a Gentleman, it is rather amazing that it succeeds as part romance, part war drama since all its action takes place at an air force cadet school. They haven’t even reached the front yet. There are no explosions or bombs bursting in air. It even shares similarities with Fred Zinneman’s star-studded From Here to Eternity (1953) years before. But that story had far more star power and a climatic event like Pearl Harbor to build the story around. Here there’s nothing quite like that. But it’s not really needed. We are reminded that mankind is inherently interesting and when you throw a bunch of them together under duress it’s a formula for heightened emotions. Certainly, the film functions because it has all the necessary components, a rebellious hero played by Gere, troubled pasts, innumerable odds and the like. However, breaking the film down to its simple plot points hardly gives the film the credit it is due. There are so many intangibles when you watch something on the screen that really gets to your gut. It’s not necessarily manipulation on the part of any one person, director, screenwriter or otherwise. It’s simply the emotional clout that the medium of film is capable of.

Certainly, the film functions because it has all the necessary components, a rebellious hero played by Gere, troubled pasts, innumerable odds and the like. However, breaking the film down to its simple plot points hardly gives the film the credit it is due. There are so many intangibles when you watch something on the screen that really gets to your gut. It’s not necessarily manipulation on the part of any one person, director, screenwriter or otherwise. It’s simply the emotional clout that the medium of film is capable of. Richard Donner (Superman) has an understanding of the balance of grand spectacle and more subtle moments. The opening aerial shot and the tenuous desert rendezvous with a helicopter churning up sand capture our attention. But it’s the little bits of humor and vulnerability that make the showmanship of Lethal Weapon ultimately worth it. There’s a vibrancy that runs through Shane Black’s script in both the action sequences and character-driven moments.

Richard Donner (Superman) has an understanding of the balance of grand spectacle and more subtle moments. The opening aerial shot and the tenuous desert rendezvous with a helicopter churning up sand capture our attention. But it’s the little bits of humor and vulnerability that make the showmanship of Lethal Weapon ultimately worth it. There’s a vibrancy that runs through Shane Black’s script in both the action sequences and character-driven moments.