I can’t even begin to comprehend what it’s like to get laid off in Tokyo. In any city, any place, any circumstance it’s one of the feelings which would instigate the formation of a lump in your throat. But Tokyo is swarming with so many people and so much competition; it seems like you would be practically swallowed up. I’m surprised there are any available jobs at all.

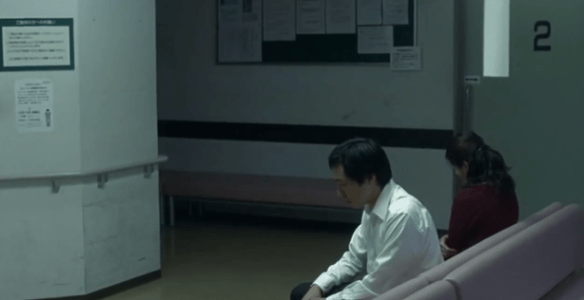

That’s what makes it especially demeaning for Ryuhei Sasaki (Teruyuki Kagawa) to go to the unemployment office. He’s long held an administrative job in a prestigious company but when he is suddenly let go, Mr. Sasaki finds that he is overqualified for any amount of work offered him at the agency. Surely, beggars can’t be choosers but no matter how many times you’ve had that phrase shoved down your throat, it doesn’t make such a reality any easier. A janitor is a far cry from a cushy desk job.

By an act of serendipitous chance, he happens upon an old school chum who has been stricken by the same fate and yet being three months in he’s seasoned at the lifestyle of keeping up appearances even as he attends the food line with the homeless. He still dresses in his suit, carries his briefcase, and feigns taking business calls. It’s an unnerving dichotomy that Ryuhei soon readily adopts as well.

But behind every man, there is usually an entire family and Tokyo Sonata is very much a dissection of the Japanese familial unit after a stressor is applied. All parties are affected. But we see the cracks even before the news breaks.

Kenji, the youngest child is caught in class with an erotic manga which he vehemently denies owning. But as an act of retaliation, he calls out his teacher in front of the class for reading similar material on the train. He purportedly saw him and the man has no defense. They meet later in a quieter exchange and his teacher simply states, “Let’s stop poking each other’s wounds and ignore them.”

It’s a morose response to deep issues of loneliness and isolation and while this particular instance pertains to love and sexual intimacy we can take this very same outlook and apply it to many of the film’s dynamics. If we keep things hidden and disregard them things might still work out.

On a whim, Kenji wants to play the piano and yet it’s for a very understandable reason. It’s because of a girl. He has a crush. Well, actually it turns out to be the woman teacher and she’s twice his age and recently divorced but that doesn’t stop him from using his month’s lunch allowance to pay for lessons without his parent’s knowledge. Again, the family operates in secret deceptions. Little white lies and overall detachment.

The eldest son, Takashi, by some peculiar circumstance, is signing up for the American military as a non-citizen for deployment in The Middle East. Of course, he too has moved forward with the plan without consulting his parents. He ambushes his mother with the news quite suddenly because he needs her written approval. He knows that she is the easier touch and doesn’t even bother telling his father at first because he knows full well the response that will come.

Their home life as represented by the dinner table feels like such a sterile environment and that’s in a scenario where none of the chinks are showing. No one says anything in fact. I feel sorry for the woman of the house. As both wife and mother, Megumi (Kyōko Koizumi ) is dutiful and maternal. She’s not necessarily aloof but the world around her feels so unloving and unfeeling. It’s hard to make a contented life for yourself when the entire atmosphere is dictated by the man of the house based on cultural precedence alone.

When the deep-rooted concept of saving face goes so far it means lying to your family I think there’s a problem. Because the lie can’t be kept forever. And even when the people close to you (or not close to you) don’t let on, eventually they know. It’s devastating to watch since it lacks any of the normal benchmarks we use to measure devastation. It reveals just how matter-of-fact something like this can be. The response is a non-response.

I know full-well that these types of circumstances play out; I’m not sure if I buy every last bit of execution in Tokyo Sonata. It feels a little too contrived. And yet even in the things that feel too perfectly planned there’s no doubt some truth. How everyone in their own way is trying to pull something off behind everyone else’s back. There is distrust in every corner of the house. If even things that aren’t altogether bad are hidden, what about the ones that are catastrophic like losing your job or little dirty secrets like reading racy manga? Multiply that across an entire society and you can readily predict the unnerving implications.

It is a picture where everyone wants to wake up and find out that it is all a bad dream and it very well could be. This is Tokyo Sonata’s true departure from any pretense of the real world and in these moments while the film loses some integrity as a true-to-life drama it undoubtedly gains some inscrutability from visions of hallucinatory nightmares. At these crossroads, we see the clearest articulation of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s background in J-Horror.

But in the end, the darker mood gives way to the most subdued of crescendos born out of an unassuming performance of “Claire de Lune.” It’s one of the few moments of palpable warmth in the film and it embodies the incomparable magnetism that music has. I can’t think of a better way to salvage Tokyo Sonata. It’s a purposeful statement of not feeling the need to say anything directly. Impeccable for a culture such as this. Maybe it serves to only exacerbate the problem. But change is incremental. It will not happen overnight. This just might be a baby step toward a more personable future.

3.5/5 Stars

The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through.

The initial inclination for seeing Arnaud Desplechin’s sprawling family drama was the presence of the estimable Catherine Deneuve. And she’s truly wonderful giving a shining, nuanced performance that makes the audience respect her, sympathize with her, and even dislike her a little bit. But the same goes for her entire family. The best word to describe them is messy. Dysfunctional is too sterile. Messy fits what they are. If you think your family is bad around the holidays, the Vuillards have a lot of their own issues to cull through. Almost Famous is almost so many things. There are truly wonderful moments that channel certain aspects of our culture’s infatuation with rock n roll.

Almost Famous is almost so many things. There are truly wonderful moments that channel certain aspects of our culture’s infatuation with rock n roll. When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey.

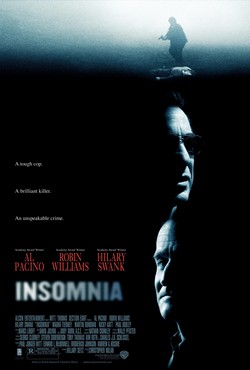

When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey. “You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch

“You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch

Peter Pan was immortalized by Disney in 1953, but as with many of the great fairy tales that they have adapted, it’s easy to forget that there was an earlier spark. These stories do not begin and end with Disney. They have a far more complex origin story and ensuing history. So it goes with J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan.

Peter Pan was immortalized by Disney in 1953, but as with many of the great fairy tales that they have adapted, it’s easy to forget that there was an earlier spark. These stories do not begin and end with Disney. They have a far more complex origin story and ensuing history. So it goes with J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. With Aaron Sorkin’s script as a road map, Charlie Wilson is a character that Mike Nichols can truly have fun with. You can easily see him getting an undue amount of delight in this man who was able to do such a momentous thing while simultaneously walking on the wild side. It had to be a good story to warrant the director’s cinematic swan song.

With Aaron Sorkin’s script as a road map, Charlie Wilson is a character that Mike Nichols can truly have fun with. You can easily see him getting an undue amount of delight in this man who was able to do such a momentous thing while simultaneously walking on the wild side. It had to be a good story to warrant the director’s cinematic swan song. In the opening moments, it becomes obvious that Charlie Wilson is not so much an easily corruptible representative as he is a sexed-up man who enjoys charming female company. He’s “Good Time Charlie” for good reason. He surrounds himself with pretty young things, doesn’t mind playing around a bit, and even has a cocaine charge hanging over him after a potentially objectionable night in Vegas. In fact, the attorney looking into his case is, interestingly enough, one Rudy Giuliani.

In the opening moments, it becomes obvious that Charlie Wilson is not so much an easily corruptible representative as he is a sexed-up man who enjoys charming female company. He’s “Good Time Charlie” for good reason. He surrounds himself with pretty young things, doesn’t mind playing around a bit, and even has a cocaine charge hanging over him after a potentially objectionable night in Vegas. In fact, the attorney looking into his case is, interestingly enough, one Rudy Giuliani.