Harry Dean Stanton, aka Lucky, feels like a bastion of a bygone era at the center of this story. The world around him still has the flavor of the West, though it has modernized. He is planted in a tradition reminiscent of The Misfits or Hud. Of course, he costarred with the likes of Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke, and his credits are strewn with all sorts of footnotes to Classic Hollywood history, from westerns to revered cult classics and arguably his greatest achievement, Paris, Texas.

Harry Dean Stanton, aka Lucky, feels like a bastion of a bygone era at the center of this story. The world around him still has the flavor of the West, though it has modernized. He is planted in a tradition reminiscent of The Misfits or Hud. Of course, he costarred with the likes of Paul Newman in Cool Hand Luke, and his credits are strewn with all sorts of footnotes to Classic Hollywood history, from westerns to revered cult classics and arguably his greatest achievement, Paris, Texas.

In his directorial debut, actor John Carroll Lynch made a love letter to his dear friend, and weak with illness, there’s a self-aware sense that this would be Stanton’s final film at 91 years of age. It proved to be true as he would pass away before the film was released in 2017. He always looked aged and world-weary decades earlier, and so you can only imagine what it is like to watch him here. Let’s make this clear. It’s an undisputed pleasure.

Because he’s a crotchety, ornery son of a gun, that’s most of the reason he’s still alive and kicking. His mornings are full of yoga in his underwear. He gets dressed in his cowboy boots and hat before stepping outside and walking everywhere he needs to go.

His favorite mental exercise is doing crossword puzzles at the local diner, he has favorite TV programs to watch, and he has a daily ritual of grabbing a carton of milk from the same family mart. All his rhythms are supported by the twang of harmonica music. It’s not quite Ry Cooder, but it gets the flavor across.

It’s unsurprising to say Lucky is profane and opinionated. He’s not afraid to say when he thinks someone has said something asinine; sometimes it just comes flying out because he’s in a foul mood. No one takes it personally. Because they know it belies a man who does have his share of tenderness.

There’s a collective responsibility where everyone cares for him, but they try not to press him too hard so he can live his life the way he wants. Still, there’s something idealized and idyllic about the small-town community.

If it’s not already apparent, Lucky has many obvious antecedents from The Straight Story by David Lynch and the road movies of Wim Wenders, like Paris, Texas. Of course, both of these films featured Stanton in critical roles. But there’s also something about the movie reminiscent of the contemporary movie Paterson by Jim Jarmusch.

Veterans like James Darren and David Lynch sit around the bar with Stanton, trading stories about romance and a lost tortoise named Mr. Roosevelt (who makes a very important cameo). It’s not some profound meeting of the minds, but to bask in their presence and see friends gathered together carries with it a special poignancy.

There are several specific passages, one where Stanton recounts his childhood and then another where he shares a conversation with a fellow veteran (Tom Skerritt), where there are very distinct echoes of Alvin Straight. It’s almost uncanny. Surely it’s not a coincidence. If they are not cut out of the same cloth, then they were formed under the same shared circumstances, be it the Depression or World War II.

Latin culture has a wonderful, well-deserved reputation for its hospitality and the importance it attributes to family across generations. When Lucky gets invited to a little boy’s fiesta for his birthday, he watches the scene, and though he’s totally welcome in that space, you can tell he desires what these people have. It’s communal and full of smiling people who know each other, who are close, and who share connections with one another.

He’s prided himself on being independent all his life, and yet he must come to terms with a life alone. Even though he makes a point of defining the difference between the choice of “being alone” and “loneliness,” that doesn’t make reality any easier to contend with. Then, Stanton elevates the moment by breaking into an impromptu rendition of “Volver, Volver.” Faces turn first surprised and then impressed that he knows all the words, and the mariachi players join in. It feels like a final stirring statement looking back on a life of 91 years.

In terms of storytelling convention, Lucky is not totally without peer. We know this. The meditative swan song, allowing talents of yesteryear a final moment in the spotlight to reflect on their celluloid careers, is a very specific and still persistent guilty pleasure of mine.

Boris Karloff in Targets, John Wayne in The Shootist, Henry Fonda in On Golden Pond, and even Peter O’Toole in Venus. The list could probably go on and on. Stanton was never as big a star as these men, but he probably garners just a fiercely devoted following, if not more so.

Lucky gets one last scene in the bar with all his “friends.” It’s not exactly an uplifting sendoff. He says we’re all eventually going to go away and we’re left with ungatz…nothing. How do you respond in the face of the bleakness? Not being a particularly religious man, he lifts a Buddhist practice he heard about in an old war story. You just have to smile in the face of your fate and accept it…

It’s a sobering worldview to come to terms with, but one must confess there is something poetic about Stanton clomping off on a desert trail and walking off into the sunset one last time. It reminds me of another fellow of a very different disposition who was always predisposed to “Smile.” That was Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp because he was a creature of unreserved hope.

I’m not sure if anyone would immediately count Harry Dean Stanton as lucky. It almost seems a bitter irony. He never had matinee idol looks. He only earned his first starring role well into his 50s. He never won major awards or plaudits. Not even a swan song like Lucky could get him that. And yet here is a man who seemed to make his own luck and by the same token wound up having a fairly charmed life.

He worked with some indelible directors, featured in mainstream successes, and earned an ardent following as a cult favorite. When I watch him in a throwaway episode of Chuck as The Repo Man, my reaction isn’t one of derision, but appreciation. By now, he is baked into our popular culture. What an extraordinary career.

3.5/5 Stars

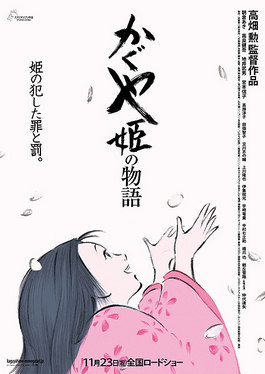

During the period of time I lived in Japan, I became acquainted with the works of Isao Takahata, and by that I mean I watched both

During the period of time I lived in Japan, I became acquainted with the works of Isao Takahata, and by that I mean I watched both

Ever since the days of his

Ever since the days of his