The title and the opening preface hint that this is a kind of fairy tale. True to form, Miracle in Milan opens with a baby being found not in the reeds like Moses but lying in a cabbage patch. He’s taken by a ditzy old lady — with a smile almost permanently placed on her face — and together, as he grows up, they share a childlike zest for life. It’s hardly a spoiler to say that she ultimately dies. He must forge on ahead with his mother’s blessing.

The boy Toto (Francesco Golisano) grows up before us in a matter of scenes, and yet his essence is still very much the same. His most salient features might be the far-off expression he wears. I can’t explain it though it seems like he’s seeing beyond the present moment into some other realm. He’s cut from the same cloth as Elwood P. Dowd and other angelic creatures who seem to walk among us.

The curious nature of the film is how it takes the visual landscape we come to equate with De Sica’s Italian Neorealism and subsequently blends it into a fantasy story which becomes a kind of fable. The dramatics are not in the same realm as Shoeshine or The Bicycle Thief, but it becomes another exploration of the plight and also the irrepressible spirit of the common people.

With this absence of natural conflict or drama, at least initially, it becomes more of a roaming, rambling character piece. This in itself is enjoyable if lightweight compared to some of De Sica’s most lasting tales of humanity. What it does allow is license to cover terrain he would not be able to reach in his other films.

The score is charged with this continual sense of peppy motion toward a certain destination though it does revise itself under many different situations. Meanwhile, the weather above feels positively empathetic with a layer of fog shrouding the city. This becomes quite literal when sunbeams break out through the dogged marine layer and leads to a frenzy of men chasing after the coveted light.

They make quite the sight: a singing, pushing, prancing, bobbing mass of humanity, all clumped together bathing in the rays. It’s a comical moment that has no equal, and yet De Sica makes his intentions quite clear even if this is just his entry point.

“It is true that my people have already attained happiness after their own fashion; precisely because they are destitute, these people still feel — as the majority of ordinary men perhaps no longer do — the living warmth of a ray of winter sunshine, the simple poetry of the wind. They greet water with the same pure joy as Saint Francis did.”

When this minor miracle dissipates and they are forced to go back to their days one voice in the crowd mutters, “Jesus wept.” There’s a bit of comedy in the scenario — visually if nothing else — but there’s also truth in these words. Because this is always cited as a definitive example of how Jesus Christ was a man of empathy; he had genuine feelings and was moved to tears for the downtrodden.

De Sica is fascinated by these types both in their innate comedy and common accessibility to us as an audience. Because we watch them as Toto with his generous spirit and warm-hearted nature helps in building a utopic colony of shanty houses. All are welcome and provided accommodations of their choosing.

This is the version of The Grapes of Wrath that Steinbeck was incapable of writing. Where the world comes together and develops into a kind of benevolent order instead of continued dissolution and stratification between classes and creeds. And when trouble does come in any form, it’s met with a resounding answer — some kind of miracle — returning things to their natural, rightful order.

In one moment their encampment becomes an oil geyser. Later with their colony in danger of being overrun by authorities armed with smoke bombs, they respond by blowing the smoke from whence it came. Fire hoses are met with an army of umbrellas, and the military forces are met with humiliations of operatic proportions.

Toto, as a character, feels like the group’s talisman, and it becomes even more pronounced when his long-departed mother swoops down and grants him a magical dove from above. It’s a prodigal, practically indecent gift. Suddenly even his charmed ability to grant happiness — the finest hobby he could ever have — goes haywire in the midst of human greed. A clamor takes over the camp, and it’s hilarious at first although it soon grows tiresome.

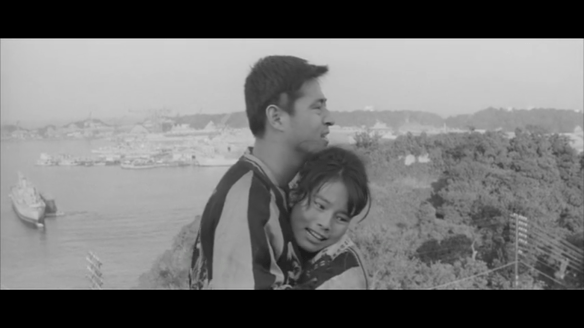

People get their fur coats, top hats, chandeliers, and anything else their greedy hearts can dream up. Toto conjures up the frenzy of Christ-like miracles though he soon becomes much more like a genie. Even statues (Alba Arnova) come alive to dance off into the night! The young maid Edvige (Brunella Bovo) feels like the one character not looking to gain something from him; she likes him for who he is, a decent young man overflowing with an almost blind faith and geniality.

I lied a bit about the dearth of conflict because the wheels of progress and wealthy men finally do overtake them effectively pushing them off the land. They find themselves unceremoniously carted off in police wagons — Toto and everyone else. However, De Sica has already conditioned us, even dared us, to maintain our belief in the unimaginable. There are still a few spritzers of magic left for the finale.

It’s somehow fitting that Milan Cathedral becomes the final backdrop for one last miracle. Although the ensuing animation and special effects are hardly spiritual in nature, it feels like a resolution befitting such a fairy tale with a bit of pixie dust Walt Disney would have no doubt appreciated.

4/5 Stars