Horst Bucholtz has always held a soft spot in my heart. There are several very simple reasons. My father’s favorite movie might be The Magnificent Seven, and I grew up watching this young raffish upstart join forces with Yul Brynner and Steve McQueen against the forces that be. Then, years later, there he was again as an old man in La Vita è Bella. Somehow it served the movie and my own history with him well, to see him this way. A mere 5 years later he would be gone.

Of course, Tiger Bay, if you’ve never been acquainted with it before, is the picture that really put him on the map, at least for English-speaking audiences. And it’s easy to see why. He was advertised once upon a time as Germany’s James Dean, and if the comparison makes a modicum of sense at all it has to do with how masculinity can be at one time violent and then sensitive. There would be no other way for him to hold the movie together with Hayley Mills so well. More on that in a moment.

I must take a moment to acknowledge my growing esteem for J. Lee Thompson in recent days because although I am a fan of Cape Fear and not so big an admirer of The Guns of Navarone, it was earlier in his career where he showed his capability with material like Yield to the Night and here in Tiger Bay. The world is easy to place, especially in England with a working-class port town acting as a window to the world. One of the men fresh off one of these ships is the youthful sailor Bronislav Korchinsky, who looks to be reunited with his lover.

Hayley Mills makes her screen debut moments later as a feisty tomboyish pipsqueak ready to roughhouse with all the other street rats. She gleams with a delightful impudence, those large searching eyes of her projecting curiosity and at times rebellion. Her aunt is always scolding her and she always scampers around bumping into neighbors on the stairs or eavesdropping on conversations she has no business in.

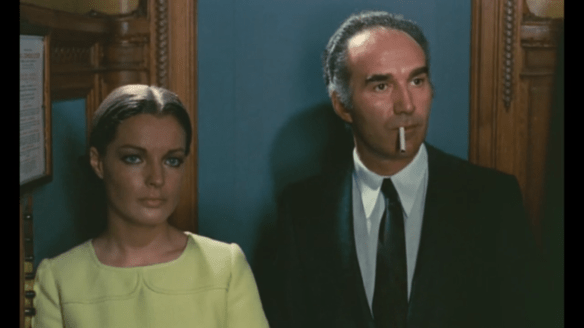

One of them is between Korchinsky and his girlfriend Anya. But the scene before us is hardly bliss. It comes seething with angst and vindictive daggers you feel like would hardly have been in vogue across the pond at the same time — at least in mainstream Hollywood. As the woman scoffs at the money he sent home and lets him have it in their native tongue, it becomes apparent this kind of gritty vitriol might only seep into an American noir picture.

In fact, if there is any immediate reference point, it’s possible to find Tiger Bay reminiscent of The Window. However, in this case, Gillie Evans (Mills) is not so much a “kid who’s cried wolf” as a serial annoyance no rational-minded adult looks to take seriously. Still, she’s an eyewitness to what looks to be a shooting. A woman’s dead and the man is on the lam. What’s more, in the moment of initial tumult they crossed paths as he streaked away, and she nicked the evidence to bring back to her aunt’s apartment. For her, this entire scene feels like a novel curiosity, but she thinks little of the consequences in the moment.

Instead, she dodges the inspector’s gentle interrogations (John Mills) before rushing off to drop into church service late, taking up her spot in the choir while still packing the purloined pistol.

It’s fitting that in one moment they seem to be singing a hymn out of Psalm 23 and suddenly the spiritual journey through the valley of the shadow of death becomes all too real. There stands a familiar face in the crowded pews and suddenly her self-assured nonchalance drops off in the middle of her solo. There’s the man!

It feels like a showdown set up for Hitchcockian dread as the church clears out and she’s left to fend for her own against the crazed young man. This can only end poorly. And yet Tiger Bay works because the villain in this equation is not a horrible human being. There are moments he could press his advantage, whether it’s pushing her to her death or doing away with her with the gun, but this is not his character.

In fact, in its best and brightest moments, Buckholtz and young Mills become the welcomed nucleus of the movie, at first as wary adversaries and then companions and finally friends capable of playacting in the morning light. For a few moments, they are able to shed all the worries of the world and enjoy being in one another’s company.

In the latter half, it takes on a different tilt altogether as a little girl, now beholden to her new friend, looks to buy him time as he looks to sneak off on a ship out to sea. We have ticking clocks and stakes, all those storytelling tricks of the trade, but the core of the entire story is the relational capital that we build. It becomes a new, far more compelling kind of movie. Because now a child must live in the ambiguity of the moment and how are they to decipher the difference between right and wrong and what those terms even mean?

The ending feels a bit prolonged and drawn out for its own good though it’s kept afloat by this underlying relational tension. A man’s life hangs in the balance as Mills drags his real-life daughter out to sea to identify the purported killer before he can get away for good.

John Mills feels generally flat and uninteresting if a mostly benevolent authority representing a prevailing moralism. Otherwise, this picture has much to offer and a colorful perspective on the world circa 1959.

Suddenly, British society, cinematography notwithstanding, doesn’t look quite so monochrome. Because of course, it wasn’t. It’s a world of Polish immigrants, vibrant Calypso music on the street corners, and foreign sailors who are not totally subservient to the British powers. It’s a reminder that ports really can be windows to the world even as they can also bring disparate people together.

3.5/5 Stars