Our Dancing Daughters is an inflection point of silent film for the very fact it stands out for setting Joan Crawford up to be in incandescent star for generations to come. She calls upon her flapper talents and bouncy effervescence fully embodying the jazz age through the character of “Dangerous” Diana Medford.

Between glitzy wardrobing and the Charleston, she exerts herself as a first-rate girl about town. Because she, like everyone else of her age demographic, is out to have a good time, dance with boys, and partake of everything else youth affords. Although it is still a silent, the added benefit of a synchronized soundtrack imbues the party scenes with life to go along with Crawford’s infectious hoofing as the balloons fall all around them.

Di’s doting friend Bea (Dorothy Sebastian) is having her own romantic tribulations, based on the searing baggage of a past love affair, now impinging on her present. Meanwhile, her greatest rival, Ann (Anita Page), a conniving opportunistic with a mother cut out of the same cloth, continues to jockey for the most advantageous romantic partner. Page is an unholy riot giving the part her all as the duplicitous gold digger who turns into a raucous and rebellious drunk. She more than holds her own as a foil and the film’s primary villain.

This is great, but we still have to contend with all the various trysts and dalliances taking place; what do they matter? All the talk of merrymaking and marrying rich gets kind of monotonous. The picture’s premise feels quite flat and it may be an added effect of antiquity.

Another complaint is how so many of the male co-stars blend together aside from John Mack Brown. They’re a generally innocuous bunch of ne’er do wells. Why are we supposed to be drawn to any of them? However, even as other elements feel staid and pat to go with the passage of time — the ending included — Crawford still manages to draw the eye.

This prevailing curiosity feels genuine and not simply an academic appreciation from a historical distance. She engages when the movie doesn’t always manage to do so. It’s not merely about looks or fashion. These are only cursory traits. But can we all agree that those great big expressive of hers were made to be in movies?

Thank heavens we have Joan Crawford and her heroine to bolster Our Dancing Daughters. It begins with garnering a certain reputation. The charm drips off of her, or better yet, it flies, landing like pixie dust on all her beaus and the audiences out in the theater seats. Crawford as a persona is coming to the fore and becoming fully apparent. She might not be the proverbial Clara Bow “It Girl,” but there’s a similar infectious magnetism even sensuality to her, bursting off the screen.

Thus, when she catches the eye of a Mr. Blaine (Brown), an eligible, very rich, young bachelor, people take note; they snicker. Diana the Dangerous is at work. But for all her reputation, Di is really a very sympathetic, vulnerable girl. It’s like Hollywood (or maybe the entire country) had not yet been burdened with the cynical inclinations of the Great Depression.

They have yet to see utter destitution or debauchery a la Baby Face or Red-Headed Woman. In 1928, women in the movies still dream of the right man, they marry for love, and the heroic ones are bound to get their hearts broken. This is so crucial to Diana. She’s hardly as superficial as we would assume.

She falls more and more for Ben only for him to make a major faux pas by going for Annikins and her false showing of pious propriety. She’s anything but. Whereas Di’s totally out there and inherently honest. And what does it get her? Heartbreak. Because Crawford has youthful good intentions, open to being wounded, and she’s more than susceptible to it.

She begins her career on this surprisingly sympathetic note, heartbroken by a man, and forced to come to terms with it. But she plays it sincerely, where all the frivolity evaporates when it really matters, and when it begins to hurt the most. This is the key to the movie. It starts to mean something. We realize why we are watching.

As her sceen life merged with her personal legacy, I’m not sure I always considered or ever imagined Joan Crawford to be a terribly sympathetic figure. She was larger-than-life, yes, but I rarely felt connected with her. At this early juncture in her career, she more than proved her mettle as a “good girl,” and when it’s done well, there’s nothing wrong with being good. In a world that’s unfair and harsh, it gives us stories fraught with genuine weight. There would still be time enough for Joan to grow scales. She was a resilient one to be sure. She had to be.

3.5/5 Stars

Recently,

Recently,

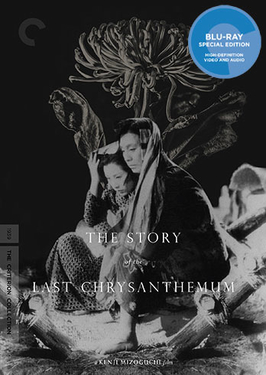

Akira Kurosawa is obviously known for samurai pictures — the famed chambara genre — and Yasjiro Ozu is most sedulous when it comes to the relational bonds between parents and children in Japanese society. However, in some sense, of the so-called “Big-Three,” it is Kenji Mizoguchi who is most obviously attached to the Japanese tradition. I mean this in the way his visual style fluidly mirrors the range of Japanese arts.

Akira Kurosawa is obviously known for samurai pictures — the famed chambara genre — and Yasjiro Ozu is most sedulous when it comes to the relational bonds between parents and children in Japanese society. However, in some sense, of the so-called “Big-Three,” it is Kenji Mizoguchi who is most obviously attached to the Japanese tradition. I mean this in the way his visual style fluidly mirrors the range of Japanese arts.