“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior

“He will be your true Christian: ready to turn the other cheek, ready to be crucified rather than crucify” ~ Minister of The Interior

Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange began as a troubling book and it becomes perhaps an even more troubling film full of volatility placed in the hands of Stanley Kubrick.

At its core are many deep-rooted issues of violence, morality, and free will all coming to the fore because of one teenage hoodlum and his rehabilitation from a life of savage juvenile delinquency.

Whereas Burgess created this parable in all sincerity to consider these very issues of morality, it’s easy to get the sense that Kubrick simply found this moral conundrum a fascinating exercise in itself. You only have to look at Dr. Strangelove to see his proclivity towards wicked wit or only to venture with 2001 to observe his penchant for deep philosophical paradigms wrapped up in the science fiction.

A Clockwork Orange has all of that and it’s a perturbing practice in both satire and science fiction. It hums with classical music and synths, shot with distorting wide-angle lenses, while also modeling Kubrick’s perfectionist tendencies.

Malcolm McDowell’s voice-overs as the main hoodlum Alex DeLarge are a major component of the film’s structure, recalling the phraseology and world developed in Burgess’s original source material. For instance, Beethoven becomes Ludwig Van. Droogs are friends. Horrorshow is good or well. Then, Ultraviolence and the old in-out don’t need much explanation.

In fact, during the course of this film, Alex takes part in equal measures of both, causing havoc with his friends and bedding a pair of girls. There is seemingly no end to his depravity and the fascinating part is that he seems to enjoy it all.

That is, until, the government steps in to reform him. Alex is sent from prison to the Ludovico Medical Facility where he is to be issued a new variation of aversion therapy. And this is where, rather ironically, the famed sequence of Malcolm McDowell, eyes wide, screaming at the images passed in front of him entered the public consciousness. His corneas actually getting scratched in the process and the images forever ingrained in our society from that point forward.

But all of this early depravity, followed by his rehabilitation are only the beginning. And it’s in these interludes that Kubrick tries to impress upon us the idea of Alex being our hero. It’s a difficult thought to deal with. But that’s of little consequence compared to the moral issues that hang in the balance here.

You cannot watch this film and not only feel somewhat dirtied but also saddened at what man is capable of doing. And it’s not only in the case of one man to another, or a small group to another. But, in this case, an entire bureaucracy of people systematically ridding their streets of crime. It’s a strange question maybe, but the question must still be asked, at what cost is all of this? It deserves our attention.

And to try and tease out some answers it seems crucial to look back to Burgess because although these are questions that undoubtedly intrigued Kubrick as well, but it was Burgess who first brought them to the fore. In this case, the author’s own religious background seems to have telling implications for this moral tale that he wove. He intended A Clockwork Orange to be a parable of what defines free will and forgiveness from a Christian perspective in particular.

What is goodness or forgiveness if we lose our free will — if we are only machines — functioning without beating hearts and all that is human within us. What kind of good would the greatest act of love in the universe be if it was done out of compulsion — not genuine love and charity?

In the case of Alex DeLarge, he no longers craves ultraviolence or his former lustful desires for women, but it has nothing to do with a change of heart. He’s simply learned to be repulsed by them. Kubrick’s picture is darkly perverse and the film ends not with the promise of the novel but a thoroughly downbeat ending that rings hollow. It becomes obvious that Alex’s core desires have hardly changed. He’s simply been conditioned to know what is “good” and “bad.” That’s perhaps an even more terrifying reality than one of violence and evil.

The story goes that when Gene Kelly crossed paths with Malcolm McDowell he coldly walked away because it was in this film that his iconic tune “Singin’ in the Rain” was notoriously tarnished. But really this entire film is a dark blot and it’s truly horribly dismal to watch at times. I cannot even manage to watch it in its entirety. Not simply for its graphic nature, but the tone that it endows. While Alex DeLarge is far from a sympathetic protagonist, it’s hard not to pity him — poor fool that he is.

3.5/5 Stars

“There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.”

“There live not three good men unhanged in England. And one of them is fat and grows old.” The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes.

The triangle with Prince Hal (Keith Baxter) vying for the affection of his father King Henry IV (John Gielgud), while simultaneously holding onto his relationship with Falstaff is an integral element of what this film is digging around at. But there’s so much more there for eager eyes. And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey.

And it’s only one high point. Aside from Welles’s towering performance, Jeanne Moreau stands out in her integral role as Doll Tearsheet, the aged knight’s bipolar lover who clings to him faithfully. The cast is rounded out by other notable individuals like John Gielgud, Margaret Rutherford, and Fernando Rey. The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in.

The original title in Italian is Ladri di biclette and I’ve seen it translated different ways namely Bicycle Thieves or The Bicycle Thief. Personally, the latter seems more powerful because it develops the ambiguity of the film right in the title. It’s only until later when all the implications truly sink in. “You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

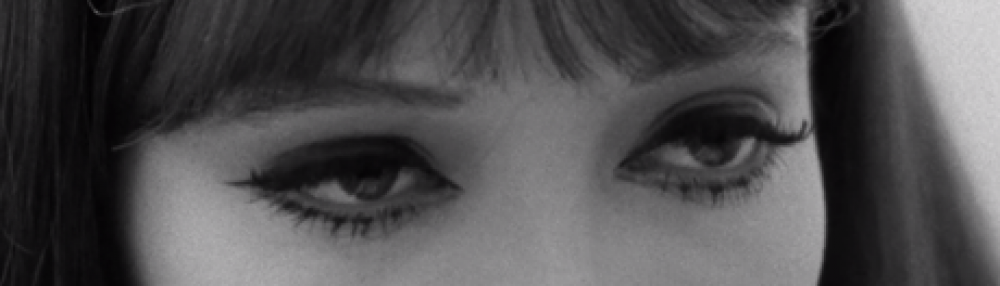

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively. Why do you watch me? -Magda

Why do you watch me? -Magda And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can.

And despite the clandestine nature of his activities he still somehow remains innocent in the eyes of the beholder. Daily he works at the post office behind the glass and in the evening he studies languages. But he’s continually drawn to this lady across the way. He feels like he knows her. He wants any pretense to meet her and so he creates a bit of fate anytime he can. However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love.

However, often times sex and love become synonymous terms and that is the underlying tension between Tomek and Maria Magdelena’s relationship. Though innocent, he wants true love, a love that transcends a simple physical act and is summed up with affection, intimacy, and an inherent closeness. He is taken with her beauty certainly but even more so he is invariably alone. Meanwhile, she is so enraptured with sex and denigrating such a grand (and admittedly messy) thing as love, to a simple physical act. She can’t understand this wide-eyed boy and his delusions. She’s ready to open him up to the way the world actually turns. And her callousness ultimately crushes Tomek’s tender heart. She broke it not by simply rejecting him, because this is a ludicrous love story, but truly obliterating any of the naive aspirations he had for love. There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps…

There is no solitude greater than that of the samurai unless it be that of a tiger in the jungle… perhaps… And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job.

And though he does call on his lovely girlfriend (Nathalie Delon), who is absolutely devoted to him, as well as making eyes at the nightclub pianist who is the main eyewitness to his hit, Jef for all intent and purposes, is alone. It’s a kind of forced solitude, a self-made exile created by his trade. After he goes through with the hit, he must shut himself off more and more. That is his job. Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful.

Robert Bresson’s film is an extraordinary, melancholy tale of adolescence and as is his customs he tells his story with an assured, no-frills approach that is nevertheless deeply impactful. I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed.

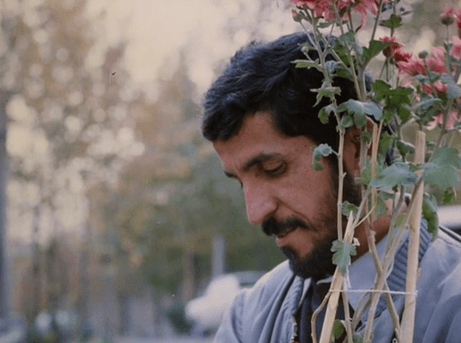

I’ve heard people like director Jean-Pierre Gorin say that there is little to no distinction between documentary and fiction. At first, it strikes us as a curiously false statement. But after giving it a moment of thought it actually makes sense, because no matter the intention behind it, the medium of film is always subjective. It’s always a created reality that’s inherently false and even in its attempts at realism — that realism is still constructed. The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time.

The beauty of Close-Up that not only does it feature the real individuals involved in this whole ordeal: There’s Sabzian playing himself, the Ahankhah family who brought the case to court, and Kiarostami appearing as well. But it blends the actual footage from the trial with reenacted scenes set up by the director as if they are happening for the first time. At face value, Model Shop is an ordinary film of little consequence but look a little deeper and it’s actually a fascinating portrait of the L.A. milieu in 1969. Part of that is due to the man behind it all.

At face value, Model Shop is an ordinary film of little consequence but look a little deeper and it’s actually a fascinating portrait of the L.A. milieu in 1969. Part of that is due to the man behind it all. John Donne is noted for writing that no man is an island, but if this film is any indication, there might be a need to qualify that statement to suggest that some women are islands — at least when portrayed by the elegiac Monica Vitti. Red Desert begins with blurred images and a high-pitched piercing melody playing over the credits. From its opening moments, two things are evident. It gives off the general sense of industry and it features one of the most extraordinary uses of color ever with the blues and grays contrasting sharply with the brighter pigments.

John Donne is noted for writing that no man is an island, but if this film is any indication, there might be a need to qualify that statement to suggest that some women are islands — at least when portrayed by the elegiac Monica Vitti. Red Desert begins with blurred images and a high-pitched piercing melody playing over the credits. From its opening moments, two things are evident. It gives off the general sense of industry and it features one of the most extraordinary uses of color ever with the blues and grays contrasting sharply with the brighter pigments. However, even if this word does reflect its share of beauty, it is Monica Vitti’s character who still embodies paranoia and disorientation with the modern civilization. In other words, she is the one out of step with the contemporary world that she finds herself in, due in part to an auto accident and a subsequent stint in a hospital. She is struggling to readjust to reality.

However, even if this word does reflect its share of beauty, it is Monica Vitti’s character who still embodies paranoia and disorientation with the modern civilization. In other words, she is the one out of step with the contemporary world that she finds herself in, due in part to an auto accident and a subsequent stint in a hospital. She is struggling to readjust to reality. As per usual with Antonioni, his film invariably feels to be altogether more preoccupied with form over content and that’s what is most interesting. It’s fascinating some of the environments he develops. Atmospheres full of billowing fog, wispy trees, stark alleyways, gridiron structures, and all the while the color red pops in every sequence. There’s no score in the typical sense, instead, the dialogue is backed by foghorns, machinery, and an occasional electronic sound effect.

As per usual with Antonioni, his film invariably feels to be altogether more preoccupied with form over content and that’s what is most interesting. It’s fascinating some of the environments he develops. Atmospheres full of billowing fog, wispy trees, stark alleyways, gridiron structures, and all the while the color red pops in every sequence. There’s no score in the typical sense, instead, the dialogue is backed by foghorns, machinery, and an occasional electronic sound effect.