Much like Sam Fuller’s Crimson Kimono (1959), Japanese War Bride’s title carries certain negative stereotypes, however, its central romance similarly feels groundbreaking, allowing it to exceed expectations.

Much like Sam Fuller’s Crimson Kimono (1959), Japanese War Bride’s title carries certain negative stereotypes, however, its central romance similarly feels groundbreaking, allowing it to exceed expectations.

The film opens during the waning days of the Korean War. A man lies incapacitated in a hospital bed, but he couldn’t be happier because he’s met the love of his life. Maybe it’s war fatigue or something else, but he simply cannot take his eyes off the pretty young nurse Ms. Shimuzu (Shirley Yamaguchi).

And although prospects don’t necessarily look that promising, since duty calls, Jim leaves that hospital bent on getting that girl for his wife. He’s serious. So serious in fact that he goes straight away to convene with Tae’s grandfather (Philip Ahn) that he might persuade him for Tae’s hand in marriage. Although warning that the road ahead will be a difficult one, the sagacious man, relents, reluctant to stand in the way of this blossoming love.

It’s after the happy couple is picked up at the train station by family and settle into the old family home, that it becomes obvious that things aren’t quite the same. They’ll be more difficult than they first appeared.

Jim’s parents and brother are welcoming enough, but there is still a necessary period of gelling as they get used to their new family member. Even Jim encourages his petite young wife to be more assertive and embrace American culture fully. She does her best.

Jim looks to build up a happy life with her as he looks to take some of his father’s land to keep a home of his own and raise crops. Tae begins to acclimate to her new life and gains the respect of the Taylor family while making a few friends including the kindly Hasagawa siblings (Lane Nakano and May Takasugi) who work at a factory nearby. The icing on the cake is when Tae announces she’s pregnant and Jim could not be more ecstatic.

Jim looks to build up a happy life with her as he looks to take some of his father’s land to keep a home of his own and raise crops. Tae begins to acclimate to her new life and gains the respect of the Taylor family while making a few friends including the kindly Hasagawa siblings (Lane Nakano and May Takasugi) who work at a factory nearby. The icing on the cake is when Tae announces she’s pregnant and Jim could not be more ecstatic.

Still, what crops up are the subtleties of racism through slight snubs and bits of insensitivity. First, the skeptical sister-in-law (Marie Windsor) drops pointed remarks towards Tae. At first, they are so veiled, they seem only a passing wisp of a word, hardly worth acknowledging. But following one of the neighbors confessing how much she hates all the Japanese, it becomes evident that all is not right in Monterrey.

One moment Tae is getting accosted by a drunken merrymaker at a party who jokingly calls her a geisha girl. Then the family is scared, rightfully so, when Mr. Taylor receives a threatening letter. It voices the opinion of an unnamed “friend” about the fact that there are rumors floating around that Tae’s baby looks fully Japanese and she has been spending time with Shiro Hasagawa. A scandal of this kind will ruin Mr. Taylor’s reputation among his fellow growers. It will ruin him period.

But most important to this story, it infuriates Jim with a fiery rage. He’s angry at all the narrow-minded folks he used to call friends. He’s mad at his family and most of all Fran for her part in Tae’s distress. It’s in these most tenuous moments that Tae decides to take her baby and seek asylum somewhere else to get away from the cultural chasm that has formed. Of course, they are reunited and there is a version of a happy ending, but it does not take away from the bottom line. They’ll still have to struggle against societal pressures and flat-out bigotry. However, if you’re in love, there are many rivers you are willing to ford and the same goes for Jim and Tae.

Japanese War Bride is continuously fascinating for the presence of Japanese within its frames. First, we have a rather groundbreaking and relatively unheard of interracial romance between the always personable average everyman Don Taylor and stunning newcomer Shirley Yamaguchi. Their scenes are tender and hold a great deal of emotional impact. It’s the kind of drama that has the power to make us mentally distraught but also imbue us with joy.

Japanese War Bride is continuously fascinating for the presence of Japanese within its frames. First, we have a rather groundbreaking and relatively unheard of interracial romance between the always personable average everyman Don Taylor and stunning newcomer Shirley Yamaguchi. Their scenes are tender and hold a great deal of emotional impact. It’s the kind of drama that has the power to make us mentally distraught but also imbue us with joy.

The film carries even more sobering underlying tension given the relative freshness of World War II. Mothers are still bitter about the deaths of their sons and that righteous anger is not discriminating between people. It only sees race. Meanwhile, Shiro and his sister reflect the times as Nisei, who were affected by internment and increased amounts of prejudice. While Shiro was imprisoned in Japan during the war, his family was interned at Tulare near Sacramento and his resentful father nearly had all of his land taken. Many other Japanese farmers were not so lucky.

For her part Marie Windsor plays her prime role as the antagonistic woman to the tee, effectively embodying all the small-minded, underhanded folks out there that live life without a genuine kindness for their fellow man. Poisoning other people’s mind just as they are poisoned, and it’s this type of rancor that leads to fear and bigotry. A breeding ground for hatred. In some shape and form, it still rears its ugly head to this day. What makes this film special is how it reflects the realities as it pertains to Japanese and Japanese-Americans. Veteran director King Vidor’s effort is a generally authentic and nuanced tale that pays his subjects the ultimate respect even in its more melodramatic moments.

3.5/5 Stars

When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey.

When you enter into the world of a film you often expect it to be perfect in your own minds-eye, following your own rationale to a logical conclusion. In that sense, Mystic River is invariably imperfect in how it ties up all its loose ends, but then again, what film really can bear that weight — and it’s all subjective anyhow. Instead, Clint Eastwood’s Boston-set drama builds off a story about three young boys and evolves into an engaging police procedural intertwining the lives and events of these three individuals. But it all starts with a game of street hockey. Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection.

Citizen Kane is so often lauded for the simple fact that never before had a director had so much creative control on a project and exercised it in such an unprecedented fashion, especially given the state of affairs in the Hollywood studio system. It’s an enigma, a stunning debut and really an astounding miracle where all things aligned for an instant of so-called perfection. At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey.

At first glance The Trial is a bare-boned parable, feeling gaunt and cavernous with empty sets and even emptier words. Everyone Josef meets talks him in circles, tirelessly — never leading to any significant conclusion, only the next diversion in his journey. If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film.

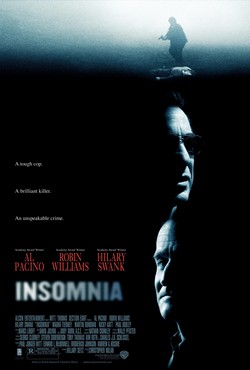

If The Trial is a hodgepodge of talent, with the presence of Americans Orson Welles and Anthony Perkins, international sirens Jeanne Moreau, Elsa Martinelli and Romy Schneider, with European backing and source material from Kafka, then it is a thoroughly intriguing marriage all the same. This film is perhaps the greatest adaptation of the work of Kafka and not due necessarily to its faithfulness to its source material, but because it displays an unmistakably Wellesian vision. The cyclical nature of the legal system pales in comparison with the fascination that comes with watching the continual creativity that is projected up on the screen — this is a hollow dream of a film. “You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch

“You and I share a secret. We know how easy it is to kill somebody.” – Robin Williams as Walter Finch One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.”

One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.” Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.

Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up.

Where to start with Liberal Arts? It’s one of those deep blue funk movies. Zach Braff tackled this issue in Garden State, and Josh Radnor does a similar thing here. Because the reality is that we live in a generation of early onset midlife crises. In the opening moments, 35-year-old Jesse Fisher (Radnor) has nearly every article of clothing he has aside from the shirt off his back stolen from a local laundromat when his back is turned. We can easily surmise that this single event epitomizes his life right now, and this is hammered home rather obviously when his unnamed girlfriend clears her belongings out of his flat. There’s no better symbol of isolation and alienation than a break-up. It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness.

It’s crucial to note that at this juncture nothing substantive builds between these two acquaintances romantically, but they do foster an immense connection. While Jesse is taken by Zibby’s personality, she, in turn, is discontent with a contemporary culture where no one dates–everybody’s casual about relationships. She feels unequivocally millennial and yet she readily admits these areas of old-fashionedness. “He spat on Balzac!”

“He spat on Balzac!” Soon Boudu is wrapped up in middle-class luxury that he didn’t ask for, at the behest of Edouard who takes an initial liking to this bushy-haired man he happened upon. After all, he is intent on playing savior and Boudu obliges. It’s in these forthcoming scenes that Renoir examines class in a satirical way, feeling rather like a precursor to some of Bunuel’s later work, without the religious undertones. And yet for some reason, we cannot help but like Boudu a lot more. True, he is loud, messy, rude and unruly, but there’s something undeniably charming about his life philosophy. There are no pretenses or false fronts. He lets it all hang out there. In this regard, Michel Simon is the most extraordinary of actors, existing as a caricature with seemingly so little effort at all. He steals every scene whether he’s propped up between two door frames or cutting out a big swath of his beard for little reason.

Soon Boudu is wrapped up in middle-class luxury that he didn’t ask for, at the behest of Edouard who takes an initial liking to this bushy-haired man he happened upon. After all, he is intent on playing savior and Boudu obliges. It’s in these forthcoming scenes that Renoir examines class in a satirical way, feeling rather like a precursor to some of Bunuel’s later work, without the religious undertones. And yet for some reason, we cannot help but like Boudu a lot more. True, he is loud, messy, rude and unruly, but there’s something undeniably charming about his life philosophy. There are no pretenses or false fronts. He lets it all hang out there. In this regard, Michel Simon is the most extraordinary of actors, existing as a caricature with seemingly so little effort at all. He steals every scene whether he’s propped up between two door frames or cutting out a big swath of his beard for little reason. Charity in a sense is met with scorn, but it feels more nuanced than, say, Bunuel’s Viridianna (1961). In many ways, Boudu seems like a proud individual or at least an independent one. He hardly asks for the charity of the wealthy, and he’s content with his lot in life, even to the extent of death. It’s also not simply chaos for the sake of it, and he hardly lowers himself to the debauchery of Bunuel’s unruly bunch. Still, he obviously rubs the more civilized classes the wrong way, by scandalizing their way of life and trampling on their social mores without much thought. It’s perfectly summed up by the last straw when a fuming Edouard incredulously exclaims, “He spat on Balzac.” The nerve!

Charity in a sense is met with scorn, but it feels more nuanced than, say, Bunuel’s Viridianna (1961). In many ways, Boudu seems like a proud individual or at least an independent one. He hardly asks for the charity of the wealthy, and he’s content with his lot in life, even to the extent of death. It’s also not simply chaos for the sake of it, and he hardly lowers himself to the debauchery of Bunuel’s unruly bunch. Still, he obviously rubs the more civilized classes the wrong way, by scandalizing their way of life and trampling on their social mores without much thought. It’s perfectly summed up by the last straw when a fuming Edouard incredulously exclaims, “He spat on Balzac.” The nerve! Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people.

Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people.