There are two types of lover-on-the-run narratives. There’s the Bonnie and Clyde/Gun Crazy extravaganza full of shoot-outs and bloodshed. Then you have the more sensitive approach of a film like They Drive By Night. You Only Live Once fits this second category thanks to two bolstering performances by Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sydney. Fonda is forever known for his plain, naturalistic delivery full of humanity. He has that quality as 3-time loser Eddie Taylor certainly, but he also injects the role with a somewhat uncharacteristic rage. In many ways, he has a right to be angry at a world that so easily writes him off and is so quick to pronounce guilt. There is very little attempt to rehabilitate the reprobate and Taylor is an indictment of that.

There are two types of lover-on-the-run narratives. There’s the Bonnie and Clyde/Gun Crazy extravaganza full of shoot-outs and bloodshed. Then you have the more sensitive approach of a film like They Drive By Night. You Only Live Once fits this second category thanks to two bolstering performances by Henry Fonda and Sylvia Sydney. Fonda is forever known for his plain, naturalistic delivery full of humanity. He has that quality as 3-time loser Eddie Taylor certainly, but he also injects the role with a somewhat uncharacteristic rage. In many ways, he has a right to be angry at a world that so easily writes him off and is so quick to pronounce guilt. There is very little attempt to rehabilitate the reprobate and Taylor is an indictment of that.

Secretary Jo Graham (Sylvia Sydney) is positively beaming the day they are releasing her boyfriend Taylor because he is finally getting the second chance he deserves. A glorious marriage follows soon after until reality breaks into the lovers’ paradise. Few people aside from Father Dolan and a few forward thinkers are willing to give Taylor grace. He is prematurely fired from his job and has no way to make the payments on the house that his wife has been sprucing up for him. Adding insult to injury, a brazen bank robbery is committed which he is wrongly accused of. It’s back to the clink and then the electric chair.

Secretary Jo Graham (Sylvia Sydney) is positively beaming the day they are releasing her boyfriend Taylor because he is finally getting the second chance he deserves. A glorious marriage follows soon after until reality breaks into the lovers’ paradise. Few people aside from Father Dolan and a few forward thinkers are willing to give Taylor grace. He is prematurely fired from his job and has no way to make the payments on the house that his wife has been sprucing up for him. Adding insult to injury, a brazen bank robbery is committed which he is wrongly accused of. It’s back to the clink and then the electric chair.

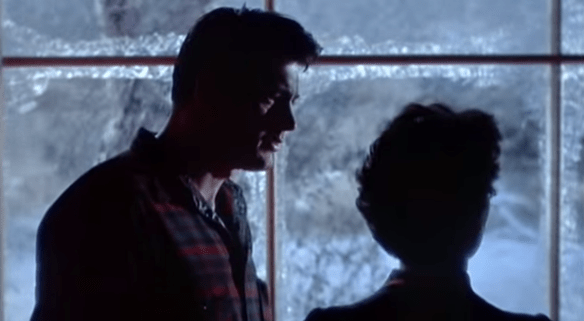

Jo is beside herself and Taylor is angered at the way the law deals with him. This justice is the most unjust imaginable, and he is about to pay the price. But Jo desperately gets him help and he tries to make a break for it.

That’s what makes a wire proclaiming his innocence all the more ironic because he will have none of it. He takes a man’s life and now his acquittal goes down the drain as quickly as he got it since he has a murder to his name. Eddie and Jo go off on the road together, looting banks and surviving the best they can with their newborn son. This is not two joyriding youngsters trying to get rich without an honest day’s work. Fritz Lang develops a more complex story with people who tried to live by the rules and found they were dealt an unfair hand.

That’s what makes a wire proclaiming his innocence all the more ironic because he will have none of it. He takes a man’s life and now his acquittal goes down the drain as quickly as he got it since he has a murder to his name. Eddie and Jo go off on the road together, looting banks and surviving the best they can with their newborn son. This is not two joyriding youngsters trying to get rich without an honest day’s work. Fritz Lang develops a more complex story with people who tried to live by the rules and found they were dealt an unfair hand.

As one of Lang’s earliest works in America, you can see some remnants of German Expressionism exported here with foggy clouds of mist engulfing the screen at times. His tale also has an interesting ambiguity suggesting that crime is not always black and white. Perhaps it has less to say about the moral degenerates or corrupt individuals in our society and more about the faulty structures that our justice system often get built around. It’s mind-boggling to think that this film came soon after the Depression meaning the bitter taste of those years was still fresh in peoples’ mouths. Nevertheless, this film is an interesting crime-filled character study.

4/5 Stars