There is a phenomenon in Japan called hikikomori (pulling inward). It mostly applies to 20-somethings. But in 2017 an article came out in The New York Times to document a different and yet somehow similar occurrence.

Many older people risk the chance of dying alone if they have no family because many live without a network of community and neighbors while in such proximity might still leave them invariably isolated. I have lived there for an extended period of time, granted as a foreigner, and yet I could feel the weight of such an environment

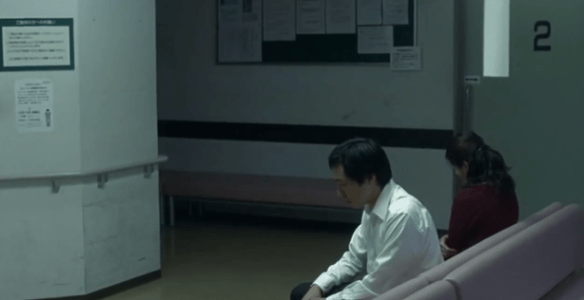

Thus, the dutiful grown children worry about their parents, about being the good son or the good daughter. Ryota’s mother is a wonderful lady. She gives him a playful slug in the stomach, tells him to his face he’s a horrible liar but always in love. Quibbles ensue between siblings over taking advantage of their mother’s good graces since she lives only off her pension following the death of her husband years back.

And yet there is a certain relish in these core relationships because even if it’s not a perfect picture you get the sense that mother and son care deeply for each other. It’s the films most gratifying interaction watching Hiroshi Abe and Kiki Kirin play off each other. Menial events take on the utmost meaning because they manage to color the characters in honest ways and the film has many of these seemingly inconsequential moments. That’s a product of its pacing.

For people who haven’t lived in Tokyo, preconceived notions of it might come from the likes of Lost in Translation (2003). Personified by ultra-hip areas like Shinjuku, Shibuya, and Harajuku touted for their nightlife and shopping. But there are a lot of other places too as director Hirokazu Kore-eda suggests. The Tokyo made up of suburbs, apartment complexes, and more ordinary landscapes. The Nerimas and Kiyoses of the world.

Coppola’s film worked because it was going for the perspective of an outsider. I enjoyed After The Storm immensely because it has the attention to detail and the touches of a local — someone who has known this terrain intimately. I distinctly remember the first time I ever came back to the states knowing I would soon be returning to Japan. And in that moment I no longer felt like a tourist but someone with a new sort of understanding. It’s crucial because it changes your entire outlook and what you deem important. The big moments aren’t as relevant as the day-to-day.

Abe’s performance is so exquisitely rendered because while the picture is by no means a comedy his various ticks, expressions, even his lumbering figure are humorous without ever truly meaning to be. And they are organic moments that never feel forced. In other words, they are human and so despite his shortcomings, there’s something that resonates about him. When we look at his life we see a bit of his restlessness. He’s still not the man he wants to be. He realizes that.

His ex-wife is seeing another man. The rich new boyfriend feels like a universal trope that doesn’t need much explanation. Meanwhile, Ryota rarely gets to see his son, only on prearranged days were he pays child support. He’s notoriously bad on making their meetings on time. That and other reasons are hints to why his wife left him. That doesn’t mean he doesn’t hold onto some wistfulness, especially where his son is involved.

Though once an award-winning author most recently he’s taken on a job as a private investigator. He says it’s only temporary — research for his latest project — but it’s been going on far too long. He’s started getting used to it and so have his coworkers.

The film’s point of departure and ultimate revelation, if there is one, comes in the wake of a typhoon. Again, living in Japan you understand that this is a fairly common occurrence. But it’s the regular person’s side of Tokyo away from the bright lights.

Trying to field lost lottery tickets in the swirling downpour or shielding oneself inside a slide at a park watching the debris fly by is enough of a diversion because the intent is to consider not so much environmental changes but how our characters change.

Of course, implicit in the translated title is that there is something new (あたらしい) about life. And yet when we get on the other side of the storm it’s difficult to know. That would be the form of a typical film. To make the before and the after drastically different. Here the characters have changed — no doubt — but externally their behavior seems all but the same. The development is incremental and internalized.

I appreciate that. In life, there is rarely a megaphone to announce change for us. Sometimes it’s imperceptible to the eye. It’s even notoriously difficult to acknowledge some changes in ourselves. And yet we know they are there. Because to our last breath, we are indubitably a work in progress. We will never be perfect. That’s part of what makes life and this film thoroughly intriguing. What’s more is that it still glimmers with a certain hopefulness.

4/5 Stars

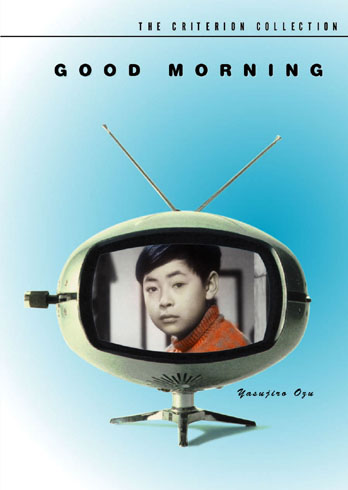

If Yasujiro Ozu can be considered foremost among Japan’s preeminent directors then there’s no doubt that Ohayo (Good Morning in English) is one of his most delightfully silly films. But that’s only on the surface level.

If Yasujiro Ozu can be considered foremost among Japan’s preeminent directors then there’s no doubt that Ohayo (Good Morning in English) is one of his most delightfully silly films. But that’s only on the surface level.

There’s something overwhelmingly soothing about Ozu, simultaneously slowing my pulse and calming my nerves. Yes, An Autumn Afternoon stands as his final film. Yes, he would sadly pass away the following year. But there’s a comfort to watching his films unfold — even his last one. The drama is everyday and somehow disarming and pleasant. We often take for granted that Ozu was not planning to end here. This was not supposed to be his last film. It just happened that way.

There’s something overwhelmingly soothing about Ozu, simultaneously slowing my pulse and calming my nerves. Yes, An Autumn Afternoon stands as his final film. Yes, he would sadly pass away the following year. But there’s a comfort to watching his films unfold — even his last one. The drama is everyday and somehow disarming and pleasant. We often take for granted that Ozu was not planning to end here. This was not supposed to be his last film. It just happened that way.

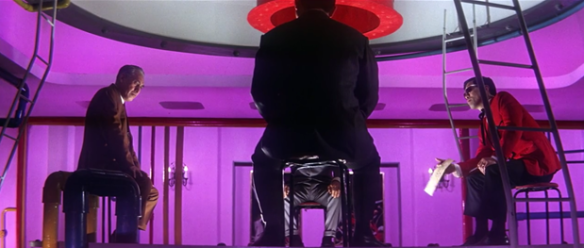

Branded to Kill is the stuff of legend inasmuch as director Seijun Suzuki offered up this wonderfully wacky, perverse, dynamic film and was subsequently dumped by his studio. At Nikkatsu they accused Suzuki of crafting an oeuvre that made “no sense and no money.” And if we watch it with the eyes of a rational, money-grubbing business mind, there’s a point to be made. Because this film is ridiculous on so many accounts, absurd in plot and action, starring an unlikely cult hero — a silky smooth hit man with prominent cheekbones and a hyper-sexualized penchant for steamed rice.

Branded to Kill is the stuff of legend inasmuch as director Seijun Suzuki offered up this wonderfully wacky, perverse, dynamic film and was subsequently dumped by his studio. At Nikkatsu they accused Suzuki of crafting an oeuvre that made “no sense and no money.” And if we watch it with the eyes of a rational, money-grubbing business mind, there’s a point to be made. Because this film is ridiculous on so many accounts, absurd in plot and action, starring an unlikely cult hero — a silky smooth hit man with prominent cheekbones and a hyper-sexualized penchant for steamed rice. Phase two follows Goro as he flaunts his tireless inventiveness as a hit man. Hiding inside a cigarette lighter advertisement and shooting his target through an adjoining water pipe for good measure. Then the femme fatale Misako slinks into his life and after a botched job, his life is in jeopardy, an unlikely adversary being his wife. She rightly characterizes them as beasts and their home life is pure chaos.

Phase two follows Goro as he flaunts his tireless inventiveness as a hit man. Hiding inside a cigarette lighter advertisement and shooting his target through an adjoining water pipe for good measure. Then the femme fatale Misako slinks into his life and after a botched job, his life is in jeopardy, an unlikely adversary being his wife. She rightly characterizes them as beasts and their home life is pure chaos. By now we have the total dissolution of the character we have known as he begins to sink into an all-out state of sniveling paranoia. He finally meets the mysterious number 1 and far from being a tense showdown, it turns into a rather pitiful scenario. They go arm and arm to the toilet, not allowing each other out of sight as number 1 decides how to finish off his hapless foe.The final showdown comes and it’s all we could ask for. Brutal, perplexing and above all undeniably unique – accented with the brushstrokes of an utterly creative mind.

By now we have the total dissolution of the character we have known as he begins to sink into an all-out state of sniveling paranoia. He finally meets the mysterious number 1 and far from being a tense showdown, it turns into a rather pitiful scenario. They go arm and arm to the toilet, not allowing each other out of sight as number 1 decides how to finish off his hapless foe.The final showdown comes and it’s all we could ask for. Brutal, perplexing and above all undeniably unique – accented with the brushstrokes of an utterly creative mind. High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments.

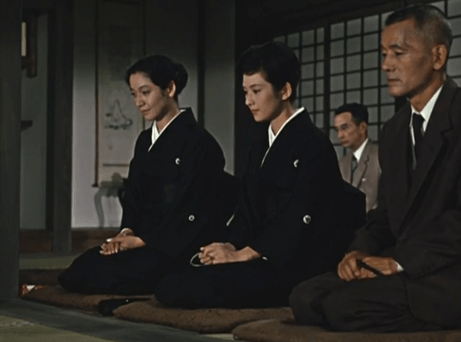

High and Low (or Heaven and Hell in the original Japanese) is a yin and yang film about the polarity of man in many ways. Gondo (Toshiro Mifune) is an affluent executive in the National Shoe Company. He worked his way up the corporate ladder from the age 16, because of his determination and commitment to a quality product. Now his colleagues want his help in forcing the company’s czar out. They come to his modernistic hilltop abode to get his support. Instead, they receive his ire, splitting in a huff. What follows is a risky plan of action from Gondo that is both fearless and shrewd. He takes all his capital to buy stock in the company so he can take over, but his whole financial stability hangs in the balance. He knows exactly what it means, but he wasn’t suspecting certain unforeseen developments. At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame.

At this point, the police are called and they arrive incognito, ready to stake out the joint and do the best they can to get the boy back safe and sound. This section of the film almost in its entirety takes place within the confines of Gondo’s house and namely the front room overlooking the city. It’s the perfect set up for Akira Kurosawa to situate his actors. He uses full use of the widescreen and his fluid camera movements keep them perfectly arranged within the frame. Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works.

Finally, with the help of Shinichi, they make a startling discovery that ties back to the kidnapper. And the boy’s drawings along with a colorful stream of smoke help them move in ever closer. What follows is an elaborate web of trails through the streets as they work to catch the culprit in his crime, to put him away for good. And it works. But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.

But High and Low cannot end there without a consideration of the consequences. Gondo has been brought low. He’s losing his mansion and must start a new job on the bottom of the food chain once more. His enemy requests a final meeting as he prepares for his imminent fate, and this is perhaps the most grippingly painful scene. Gondo’s face-to-face with the man who made him suffer so much. Toshiro Mifune’s violent acting style serves him well as he wrestles so intensely with his own conscience. And yet at this junction, he is past that. What is he to do but listen? In this way, it’s difficult to know who to feel sorrier for — the man who is resigned to a certain fate passively or the one who goes out proud and arrogantly against death. Both have entered some dark territory and it’s no longer about high or low or even heaven and hell. They’re stuck in some middle ground. An equally frightening purgatory.