“You don’t have to die to keep the John Doe ideal alive. Someone already died for that once. The first John Doe. And he’s kept that ideal alive for nearly 2,000 years.” – Barbara Stanwyck as Ann Mitchell

In their final collaboration, Capra and Riskin draw on the same cisterns with their usual success. Even the opening images matched with music, summons strains of unmistakable Americana from “Take Me Out to The Ballgame” and “Oh Susanna” mixed with “Roll Out The Barrel.”

It taps into the precise sentiment all but embodied and propagated by all their pictures together. There’s always a point of inception. In this case, it begins with something bad. The Free Press gets axed for a new and improved streamlined paper and with the changes, some of the faithful employees get knocked off too. Among them is feisty newspaperwoman Ann Mitchell (Barbara Stanwyck) supporting her family on her measly paycheck. Now the new regime wants to take that away from her too.

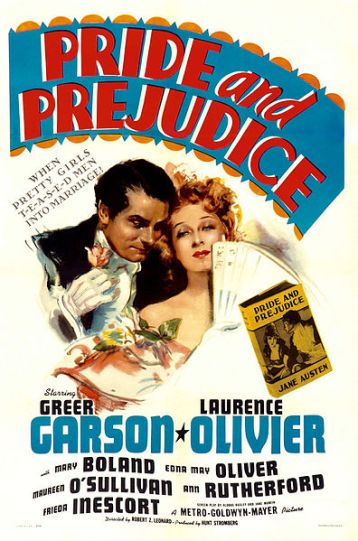

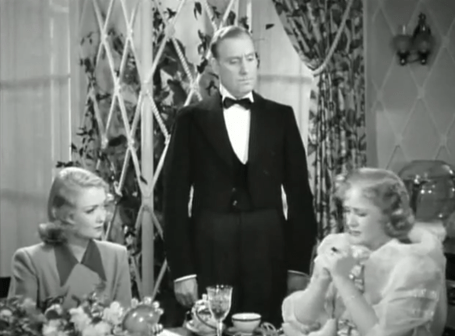

I must open with this. I love Barbara Stanwyck to death. There’s something so energetic and alive about her, even the tonalities of her voice feel fresh and appealing. 1941, without a doubt, was a bumper crop of a year for her — the finest of her career — and she churned out three classics. The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, and Ball of Fire all capitalized on her ready-made brand of wit, strength, and innate beauty.

Twice she plays Gary Cooper, once it’s Henry Fonda, and yet in all cases, she falls in love with the man. So much so she’ll fight to get them back. And they can be fiery in other movies, but when she shares the screen with them, they don’t have to be. She can supply enough verve and vivacity to cover both of them. It’s phenomenal to watch how she effortlessly commandeers scenes.

But this is jumping the gun. For the time being, she hasn’t met her man yet. She’s too busy being miffed, trying desperately to dream up one final hair-brained idea to reclaim her job. It comes with dreaming up an idealized man — the man she will come to fall in love with.

The origins are innocent. She wants to get back at the brusque editor (James Gleason) trimming the fat like there’s no tomorrow. Her Lavender and Old Lace column is too blase for what they’re looking for. They want fireworks. Well, she’s prepared to give them absolute dynamite. Because in a Capra-Riskin picture, ideas can flip the world upside down.

This one involves a universal “John Doe,” who has sent a letter to the editor to protest the state of the world and the lack of brotherly love. As an act of protest, the mystery man asserts he will commit suicide by jumping off a government building on Christmas Eve merely on principle. While it’s one last feisty stab at keeping her light burning, the John Doe column starts a wildfire across the country.

It’s a national phenomenon. People are clamoring for action to stop this preventable tragedy. They want John Doe to be reinstated into society, even bending over backward to offer charity. The idea is almost too big. The paper is forced to back up the lie by instigating a national search for the one and only John Doe.

Wouldn’t you know it, among all the bums and vagabonds is Gary Cooper, tall and self-effacing as ever, accompanied by his buddy, The Colonel (Walter Brenan), a man continually suspicious of the helots. Moments later, Stanwyck beams up into Coops big brown eyes forming an instant connection. He’s the one.

With their substantial public support and the silent backing of a perfidious magnate D.B. Morton (Edward Arnold), Meet John Doe fits easily on the same plane with Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and A Face in The Crowd.

Long John Willougby (Cooper) looks to be propped up as a spineless ‘yes man’ and yet even with his national sway, he’s hesitant to use it. This makes him the utter antithesis of Lonesome Rhodes. He has his own choices to make because as it goes, indecision is a decision in its own right.

Thankfully, the flimsy gimmick deepens as Stanwyck humanizes it with her deceased father’s words. It’s no longer a totally phony-baloney stunt. She legitimizes it and falls for the ideal she’s created in its wake. The man standing in for her vision is the washed-up big-league pitcher who is simultaneously falling for her.

It’s pure Capra, pure Riskin, even as a rival newspaper tries to bribe him with 5,000 clams to read an alternate speech, effectively ousting himself as a phoney. He’s can’t help but be smitten so he goes forward as planned, and there’s arguably no better man to orate the words than Gary Cooper. He calmly calls on his fellow countrymen to tear the fences down between neighbors because the trouble with the world is people being sore at each other.

A grassroots populism shoots up across the country in response to his amicable radio rally. John Doe clubs dotting the country are almost a kind of humanistic church meeting ground, altogether apolitical and not overtly religious.

Regis Toomey represents the masses as one of the many folks taken up by Doe’s words. Ann Doran is all but uncredited as his doting wife and the guiding light behind his resolve. His candid soliloquy speaks to the same messages of brotherly love. It’s Williloby’s first realization that he’s a part of something far larger than himself. He has some sort of concrete responsibility to these people, whether real or imagined.

The story could end here on this most saccharine note if not for the customary sinister twists alluded to by the foreboding closeup on Mr. Morton as he eavesdrops on his help. He knows he’s in on something that he can use for his personal ends. The greedy are capable of taking something pure and twisting it with their duplicitous intentions.

He proves just how Machiavellian he is willing to stoop, ready to kill an idea when it gets in the way of his political ambitions. Prepared to ground Doe into the dirt and turn the whole nation against him with his amble sway in the media. The man who once promoted him, calls John out as a fake, a man paid off with 30 pieces of silver like Judas Iscariot — the most ignominious traitor the world has ever known.

Stanwyck can’t save him in the moment and she cries out, “They’re crucifying him!” The same people who loved him. A fickle generation fed on lies. Now with the biblical imagery increasingly clear, John Doe is prepared to be the sacrificial figure they don’t deserve.

The following Christmas Eve is understated and dismally captured. Instead of a bridge in Bedford Falls, it’s the top floor of City Hall where our man bides his time, resolved to jump to his death as not only an act of silent protest but sacrificial love.

Capra famously shot about four or five different endings to the picture trying to figure out how to resolve the story in a satisfactory manner. Whether you agree with the choice or not, one must admit he kept with the unifying thematics of his oeuvre. For me, Stanwyck is the standout MVP to the very last scene.

4/5 Stars