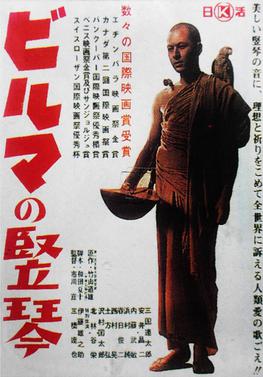

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

If anything, it humanizes the Japanese point of view and, rather remarkably, it does this so soon after the war’s conclusion. They were a nation deeply concerned with honor and the only way to get past such an egregious defeat was to frame it in such a way that empowered them for the future.

Because the men who came out of the war unscathed would be the shoulders on which to build a new democracy. You see that even in Ichikawa’s portrayal of the “enemy,” in this case, the English. There is no obvious ill-will. In fact, you could even consider it surprisingly laudatory. Because The Burmese Harp is not concerned with any types of residual politics or long-harbored injustices.

One could make the case it’s a far more universal and a far more moving portrait of the wartime landscape. The story, adapted from a Japanese children’s tale, plays out rather like a parable.

In the waning days of the Burma campaigns, a Japanese Captain named Inouye (Rentaro Mikuni), with a background in music teaches his group of men chorale arrangements which they sing to maintain their morale while they march and during their idle hours. One of their company, Private Mizushima (Shoji Yasui), quickly picks it up and becomes especially skilled at playing the harp to accompany their songs.

One evening they find their position in a local village surrounded by British soldiers in the night. The tense scene is diffused by music in a mutual connection reminiscent of the Christmas cheer in Joyeux Noel.

They learn that Japan has officially surrendered and so they lay down their arms peaceably. Although fearful and demoralized by months of struggle, they resolve to weather it all together. But one of their members is called upon to try and get some of their comrades to stand down before the British blast them to smithereens.

Mizushima volunteers to be the one to undertake this initial task as a liaison to try and avoid the needless loss of more countrymen. It is not to be. Even as the war is already over, it’s this event that proves to be galvanizing in the private’s new position as a missionary of mercy. After being rehabilitated by a monk, he takes on their dress and shaves his head compelled to give a decent burial to all his fallen comrades.

Moved by the memorial hymn sung over the dead Japanese soldiers at the British Hospital, he realizes what his final calling must be. It’s easy to wager that the film’s most poignant moments occur in conjunction with song. In many of the best interludes, we hear the voices ringing out amid nature whether it’s the shade of the forest or the cleared terrain of a military encampment you can sense the notes rising up into the heavens with the strains of angelic melodiousness.

The same songs lift the spirits of our characters, comforts their souls, and gives them the resolve to push onward for the greater good. It has to do with an unswerving belief that each individual life holds dignity. Despite their many spiritual differences, there’s no doubt that this is a conclusion arrived at by both Buddhism and Christianity. Yes, the ugliness is unavoidable. But just as prevalent are immense reservoirs of beauty.

Mizushima is compelled in the inter most catacombs of his being to rescue the bodies of his brothers-in-arms that their spirits might rest in peace for posterity. It seems like such a small even insignificant act especially in response to such a cataclysmic war. But it’s one man’s calling. It is not for a mere man to know the answers to all the plaguing questions. All we can do is ease the suffering. For him, it is something. For him, it is enough.

What lends urgency to the story is the very fact that Mizushima’s entire company is frantically trying to obtain news of his whereabouts as they are getting ready to be shipped home. One of their most faithful messengers is a kindly old lady who learned some Japanese dialect. She can only give them small morsels but they cling to some hope. First, they think he’s been killed. Then, they think they’ve passed him on a bridge. Finally, they get their closure.

The candor is nearly startling especially put in relief with Ichikawa’s later work Fires on The Plain which paints a starkly different picture (or a very different side of the same picture). Likewise, this movie is aided by a script penned by his wife and close collaborator Natto Wada.

What we are left with are clear resounding strains of pacifism but by no means does it feel belligerent. What is conveyed is the sheer meaninglessness of war. However, it’s done through different avenues than his later work.

The film is bookended by the phrase, “The soil of Burma is red and so are its rocks.” The mind quickly flies to the pints of blood that were spilled across this terrain. It’s a grim reminder and yet The Burmese Harp, despite being a bittersweet tale, does boast hope. In the wake of war, such hopefulness is indispensable. You cannot progress without it.

4/5 Stars

Anime is very much a Japanese art form denoted by its style, the visuals, and even the depiction of its characters with wide eyes all the better to convey emotions. Oftentimes the images onscreen are a great deal more stagnant than the real-time action that American animators try and replicate with a greater frame rate.

Anime is very much a Japanese art form denoted by its style, the visuals, and even the depiction of its characters with wide eyes all the better to convey emotions. Oftentimes the images onscreen are a great deal more stagnant than the real-time action that American animators try and replicate with a greater frame rate.

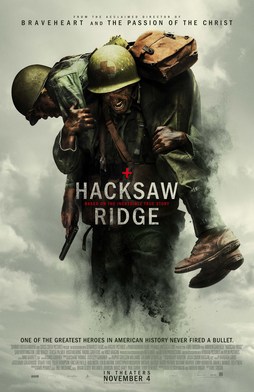

Hacksaw Ridge is not for the squeamish, its greatest irony being that for a film about a man who took on the mantle of a conscientious objector and would not brandish firearms, it is a very violent film, even aggressively so. But Mel Gibson, after all, is the man who brought us Braveheart (1995) and The Passion of the Christ (2004) while starring in The Mad Max and Lethal Weapon franchises.

Hacksaw Ridge is not for the squeamish, its greatest irony being that for a film about a man who took on the mantle of a conscientious objector and would not brandish firearms, it is a very violent film, even aggressively so. But Mel Gibson, after all, is the man who brought us Braveheart (1995) and The Passion of the Christ (2004) while starring in The Mad Max and Lethal Weapon franchises. “My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan

“My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out.

Upon being thrown headlong into Christopher Nolan’s immersive wartime drama Dunkirk, it becomes obvious that it is hardly a narrative film like any of the director’s previous efforts because it has a singular objective set out. There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand.

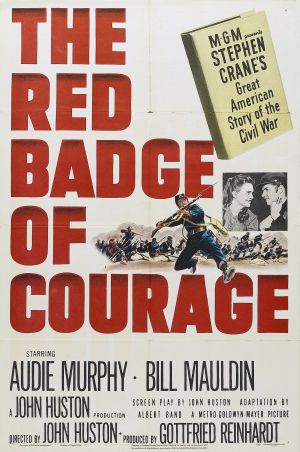

There’s something remarkably moving about the beginning of Saving Private Ryan. I’ve only felt it a few times in my own lifetime whether it was family members recognizing names on the Vietnam Memorial tears in their eyes or walking over the sunken remains of the U.S.S. Arizona at Pearl Harbor. It’s these types of memories that don’t leave us — even as outsiders — people who cannot understand these historical moments firsthand. Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text.

Stephen Crane’s seminal Civil War novel was made to be gripping film material and although my knowledge of the particulars is limited John Huston’s story while streamlined and truncated feels like a fairly faithful adaptation that even takes some effort to pull passages directly from the original text.