Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda

Are you leaving room for Jesus?~Amanda

You know it. Catholic school forever.~Jim

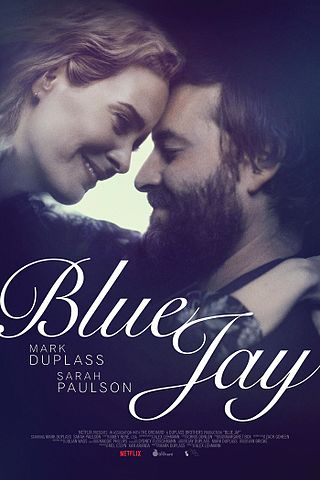

Is it true that nostalgia always feels like it should be in black and white? If that sentiment is true there’s a rooted purpose in Blue Jay’s muted black and white tones that run deep. So often we consider it as a gimmick in the modern film spectrum but here it works.

This is a story of boy meets girl again. Now they are both 20 years older no longer naive high school sweethearts and he’s lost his mother and she’s now married to a man many years her senior. They’ve moved on you might say as is customary with those living life. But this day they run into each other at the local market. The stage is set for a fulfilling reunion.

However, in the opening interludes, we don’t know anything about either of them. Jim (Mark Duplass) with his scruffy ensemble and Amanda (Sarah Paulson) with her knit cap. For us, both of them have a clean slate but for the two of them meeting again is a mixed bag of emotions.

In these moments, it seems like all parties involved with the film are trying to make everything as unbearably awkward as possible. Is this the way movies work? A script must always acknowledge the sheer awkwardness of it all, creating certain pretenses, and piddling around with what characters are actually thinking. Is it simply a mean trick of a screenwriter to try and pull us into his story, in this case, Mark Duplass, or is there actually some truth to it all?

Are people actually this awkward in real life? Heaven forbid we actually act like this when we’re together or worse yet with someone we have a crush on. I can answer that rhetorical question almost instantly as a multitude of cringe-worthy moments surge to the fore. So yes, there’s probably some truth here and yes, Duplass is drawing us in. Of course, the final joke is that the film utilized no script at all only simple character arcs to arrive at its conclusions.

Still, these moments are only the setup. It’s not Blue Jay at its best. The film comes into its own as time progresses and the contours of the two characters become more evident with every memory they manage to conjure up and every little thing they do together that takes them through their old routines. They stop at the local liquor store and the proprietor (Clu Gulager) with his cowboy hat welcomes them in like old times. Whether or not they know his unassuming roots in western television lore is another thing altogether.

Then, they make the rounds of Jim’s old family home, the house of his deceased mother which is left pretty as it was when he was still a teenager. Piled high with treasures, clothing, trinkets, romance novels, and other artifacts from that long bygone era known as the 1990s.

They let the nostalgia waft over them as they reminisce together, playing their admittedly dorky version of “House” as Mr. and Mrs. Henderson and exhibiting the funkiest ’90s dancing as two of the whitest kids you know. But they accept their quirks and how dorky they are. That’s the fun part as they remember their younger days.

It’s in these wistful and yet still somehow carefree moments that the film recalls one of my favorite lyrics,

Here’s to the twilight

here’s to the memories

these are my souvenirs

my mental pictures of everything

Here’s to the late nights

here’s to the firelight

these are my souvenirs

my souvenirs

I close my eyes and go back in time

I can see you’re smiling, you’re so alive

we were so young, we had no fear

we were so young, we had no idea

that life was just happening

life was just happening

In the final stretch there some big reveals, there’s some of the drama we were expecting, some of the histrionics that we were wary of from a film such as this. After all, they’re in a confined space together with so many emotions still dwelling inside. You wonder about the old dichotomy that men and woman can either be married or unmarried. They’re never just friends because the boundaries become too difficult to maintain. The self-restraint too difficult to manage even in the most self-controlled of us all. After all, metaphorically speaking, a man can’t scoop burning coals into his lap without burning himself.

But we’ve come to care about the characters enough that’s there no sense that this is some shallow attempt to play with our emotions and get a rise out of us. Somehow it feels like a less flawed iteration of Your Sister’s Sister because it’s frank but never purposely crass and more than its predecessor Blue Jay feels true blue and sincere. It’s a more intimate even heartfelt drama that wins its audience over.

These characters deservedly earn our respect and even in the modicum amount of time they do well to build a rapport with their audience. They do the heavy lifting by opening up and we are called to respond accordingly. The tears and the laughter are intermingled. The regrets with the reality. The way we perceived things would look farther down the road and how they look now. I guess you could say that it’s the blue jay way–reflected precisely by the path this film takes.

It’s the memories and the dashed hopes it starts to pull out of the closets back out into the open. It’s joy. It’s laughter. It’s pain. It’s heartbreak. And as is usually the case with life the ending is unwritten. That’s why they’re still making films like this, now until the end of time.

3.5/5 Stars

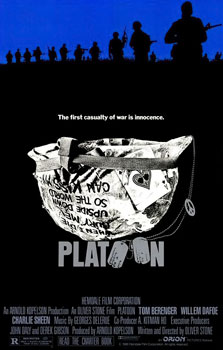

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

It’s a rather interesting parallel that Charlie Sheen is playing much the same role his father did in Apocalypse Now. At least in the sense that they become our entry point into the mire of war, specifically in Vietnam. But where Apocalypse seemed to belong more so to Brando or even Duvall, Platoon is really Willem Dafoe’s film. At least he’s the one who makes it what it is. His final moment is emblematic of the entire narrative.

After watching this film two things become astoundingly obvious. Damien Chazelle has an equally unquenchable passion for film and for jazz. He’s also extremely bold, going all the way when it comes to choices as a director with everything from camera set-ups, lighting, staging, even casting. In fact, let’s start right there.

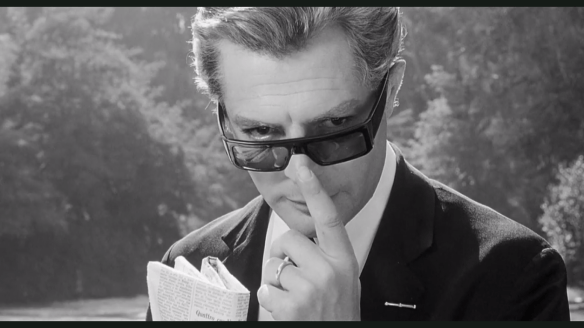

After watching this film two things become astoundingly obvious. Damien Chazelle has an equally unquenchable passion for film and for jazz. He’s also extremely bold, going all the way when it comes to choices as a director with everything from camera set-ups, lighting, staging, even casting. In fact, let’s start right there. Fallen Idol is a fascinating film for how it develops inner turmoil. It’s earnestly interested in the point of view of a child and as such, it functions on multiple levels –that of both kids and adults. Philippe’s (Bobby Henrey) home is the embassy as his father is a French ambassador who is always away on the job. So Phil’s a little boy who is perpetually in the care of servants. Namely the authoritarian Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel) and her good-natured husband (Ralph Richardson).

Fallen Idol is a fascinating film for how it develops inner turmoil. It’s earnestly interested in the point of view of a child and as such, it functions on multiple levels –that of both kids and adults. Philippe’s (Bobby Henrey) home is the embassy as his father is a French ambassador who is always away on the job. So Phil’s a little boy who is perpetually in the care of servants. Namely the authoritarian Mrs. Baines (Sonia Dresdel) and her good-natured husband (Ralph Richardson).

Body Snatchers works seamlessly and efficiently on multiple fronts, both as science fiction and social commentary. Don Siegel helms this film with his typical dynamic ease putting every minute of running time to good use. The screenwriter, Daniel Manwaring, put together perhaps one of the greatest political allegories ever penned and, on the whole, it’s a taut thriller combining sci-fi and horror to a tee.

Body Snatchers works seamlessly and efficiently on multiple fronts, both as science fiction and social commentary. Don Siegel helms this film with his typical dynamic ease putting every minute of running time to good use. The screenwriter, Daniel Manwaring, put together perhaps one of the greatest political allegories ever penned and, on the whole, it’s a taut thriller combining sci-fi and horror to a tee.