Thank you to Classic Film and TV Cafe for hosting this year’s 6 Films — 6 Decades Blogathon for National Classic Movie Day!

It’s been a perennial enjoyment the last few years to hear the topic and then go to work curating a personal list. In keeping with the impetus of the occasion, I wanted to share some lesser-known films that I’ve enjoyed over the course of the last year or two.

This is a list of new favorites if you will, ranging from the 20s to the 70s, and like every year, I will do my best to fudge the rules to get as many extra recommendations in as I can. I hope you don’t hold it against me and hopefully, you will find some of these films as enjoyable as I did.

Without further ado, here are my picks, and once more, Happy National Classic Movie Day!

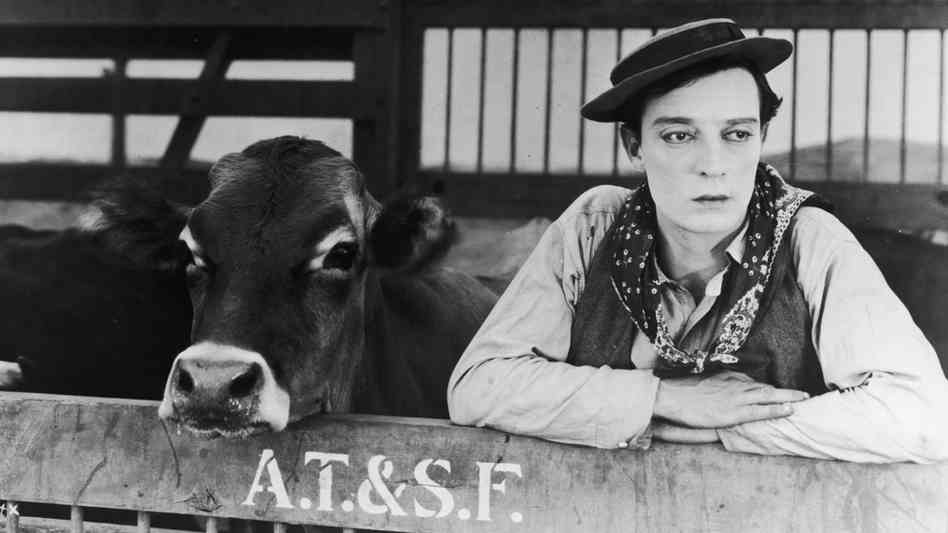

Go West (1925)

I feel like in the 21st century — and this is only a personal observation — Buster Keaton has grown in esteem. Chaplin was always the zenith of cinematic pathos and heart. He cannot be disregarded as the one-time king of the movies. But Keaton, with his Stone Face and irrepressible spirit, is also strangely compelling in the modern arena we find ourselves in.

In pictures like Sherlock Jr. and Steamboat Bill Jr., he’s part magician, part daredevil stuntman, who, in the age before CGI, dared to play with our expectations and put himself in all sorts of visual gags for our amusement. It’s extraordinary to watch him even a century later. But whereas The Tramp was taken with Edna Purviance, the pretty blind girl (Virginia Cherill), or even Paulette Goddard’s feisty Gamin, Buster Keaton’s finest leading lady could arguably be a cow.

Go West earns its title from the potentially apocryphal quote from Horace Greeley, but the glories of the movie are born out of Keaton’s ability to take on all the nascent tropes of the Western landscape. He’s the anti-cowboy, the city slicker, the cast aside everyman, who doesn’t quite fit the world. And yet he’s still a hero, and he gets the girl in the end. You might think I’m being facetious, but I’m not. Keaton seems to love that cow, and it’s strangely poignant.

The Stranger’s Return (1933)

It’s remarkable to me that a film like The Stranger’s Return rarely seems to get many plaudits. Lionel Barrymore is a hoot as a cantankerous Iowa farmer, playing what feels like the affectionate archetype for all such roles and welcoming his city-dwelling granddaughter into the fold.

Miriam Hopkins has rarely been so amiable and opposite Franchot Tone, King Vidor develops this profound congeniality of spirit played against these elemental images of rural American life. It’s a collision of two worlds and yet any chafing comes more so from the hardened hearts of relatives than the nature of one’s upbringing. It moved me a great deal even as I consider the different worlds I’ve been blessed to frequent.

If you want to go down other cinematic rabbit holes, I would also recommend Ernst Lubitsch’s The Broken Lullaby with Barrymore. For Miriam Hopkins, you might consider The Story of Temple Drake, and for director King Vidor, I was equally fascinated by the Depression-era saga Our Daily Bread.

The Children Are Watching Us (1944)

During the beginning of 2021, I went on a bit of an Italian neorealist odyssey, beginning with some of the less appreciated films of Vittorio De Sica (at least by me). While Bicycle Thieves is a high watermark, even an early film like The Children Are Watching Us shows his innate concern for human beings of all stripes.

This is not a portrait of economic poverty as much as it depicts poverty of relationships and emotion. In what might feel like a predecessor to two British classics in Brief Encounter and Fallen Idol, a young boy’s childhood is fractured by his mother’s infidelity. While his father tries to save their marriage and they gain a brief respite on a family vacation, these attempts at reconciliation are not enough to save their crumbling family unit.

What’s most devastating is how this young boy is left so vulnerable — caught in the middle of warring parents — and stricken with anxiety. In a tumultuous, wartime landscape, it’s no less miraculous De Sica got the movie made. It’s not exactly a portrait of the perfect fascist family. Instead, what it boasts are the pathos and humanity that would color the actor-director’s entire career going forward.

Violent Saturday (1955)

Color noir is a kind of personal preoccupation of mine: Inferno, Slightly Scarlet, The Revolt of Mamie Stover, Hell on Frisco Bay, and a Kiss Before Dying all are blessed with another dimension because of their cinematography. Violent Saturday is arguably the most compelling of the lot of them because of how it so fluidly intertwines this microcosm of post-war America with the ugliness of crime.

Richard Fleischer’s film takes ample time to introduce us to the town — its inhabitants — and what is going on behind the scenes. Three men, led by Stephen McNally and Lee Marvin, spearhead a bank robbery plot. But we simultaneously are privy to all the dirty laundry dredged up in a community like this.

These criminals are the obvious villains, and yet we come to understand there’s a moral gradient throughout the entire community. The out-of-towners are not the totality of evil just as the townsfolk aren’t unconditionally saintly. The picture boasts a cast of multitudes including Victor Mature, Richard Egan, Silvia Sidney, Virginia Leith, Tommy Noonan, and Ernest Borgnine. The ending comes with emotional consequence.

Nothing But a Man (1964)

Nothing But a Man was a recent revelation. It was a film that I meant to watch for years — there were always vague notions that it was an early addition to the National Film Registry — and yet one very rarely hears a word about it. The story is rudimentary, about a black man returning to his roots in The South, trying to make a living, and ultimately falling in love.

However, the film also feels like a bit of a time capsule. Although filmed up north, it gives us a stark impression of what life in the Jim Crow South remained for a black man in the 1960s. The March on Washington was only the year before and The Voting Rights Act has little bearing on this man’s day-to-day. The smallest act of defiance against the prevailing white community will easily get him blackballed.

I’ve appreciated Ivan Dixon for his supporting spot on Hogan’s Heroes and his prolific directorial career (Even his brief stints in A Raisin in The Sun, Too Late Blues, and A Patch of Blue). Still, Nothing But a Man, showcases his talents like no other. Likewise, I only just registered Abbey Lincoln as a jazz talent, but I have a new appreciation for her. She exhibits a poise and a genuine concern that lends real weight to their relationship. It’s not simply about drama; it’s the privilege to observe these moments with them — to feel their elation, their pain, and their inalienable yearning for dignity.

Les Choses de la Vie (1970)

Even in the aftermath of the cultural zeitgeist that exploded out of the French New Wave, the likes of Godard, Truffaut, Rohmer, Chabrol, and Rivette et al. released a steady stream of films. One of the filmmakers you hear a great deal less about — and one who was never associated with this hallowed group — was Claude Sautet.

Still, in his work with the likes of Romy Schneider and Michel Piccoli, he carved out a place worthy of at least some recognition in the annals of French cinema. If one would attempt to describe his work with something like The Things of Life, you could grasp at a term like “melodrama,” but it is never in the fashion of Douglas Sirk. It’s a film of melancholy and a subtler approach to splintering romance.

It somehow takes the motifs of Godard’s Weekend with the constant vicissitude of the continental Two for The Road to alight on its own tale of love nailed down by the performances of Piccoli and Schneider. They are both caught in the kind of fated cycle that bears this lingering sense of tragedy.

Honorable Mentions (in no exact order):

- Dishonored (1931) Dir. by Josef Von Sternberg

- Pilgrimage (1933) Dir. by John Ford

- TIll We Meet Again (1944) Dir. by Frank Borzage

- Bonjour Tritesse (1958) Dir. by Otto Preminger

- Scaramouche (1952) Dir. by George Sidney

- Pale Flower (1964) Dir. by Masahiro Shinoda

- Courtship of Eddie’s Father (1963) Dir. by Vincente Minnelli

- Girl With a Suitcase (1961) Dir. by Valerio Zurlini

- Sergeant Rutledge (1960) Dir. by John Ford

- Buck and The Preacher (1972) Dir. by Sidney Poitier

- Cooley High (1975) Dir. by Michael Schultz

- My Name is Nobody (1973) Dir. by Tonino Valerii

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”

“There’s not one woman in a million who has ever found happiness in the back streets of any man’s life.”