Physics and Mathematics are the two primary focuses of Marie Curie’s life. In the early days, when she was one of the few solitary women in a Parisian sphere of academia, dominated by dismissive men, she still went by her maiden name and took on the rigors of study with ardent relish.

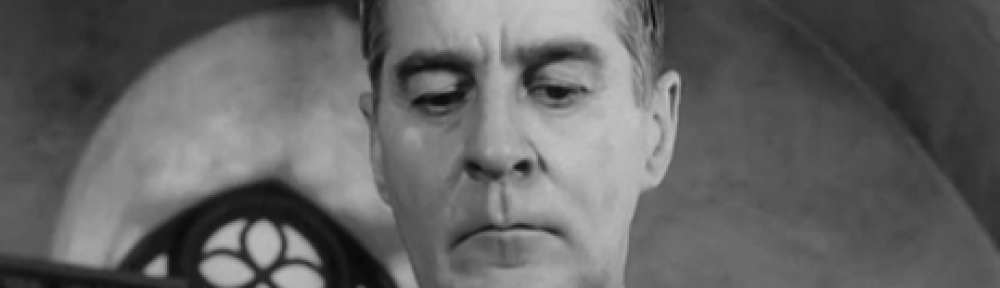

Thus, when her kindly professor (Albert Basserman), the prototypical white wizard with a likable twinkle in his eye, invites her over to his home to meet famed professor Pierre Curie (Walter Pidgeon), she jumps at the opportunity, purely on a professional basis. However, I will not suggest for even one moment Madame Curie takes its material into anything close to unconventional territory.

What looks to be an intimate affair turns out to be a bustling party packed with people. The two academics feel sorely out of place amidst the socializing and gravitate toward one another even more dramatically. There’s nothing concrete at the moment because we must remember these are two people with the utmost sense of dignity. They’re able to counter one another with a certain genteel propriety, not the klutzy screwball meet-cutes of some of their contemporaries. This no doubt plays to their personal advantage.

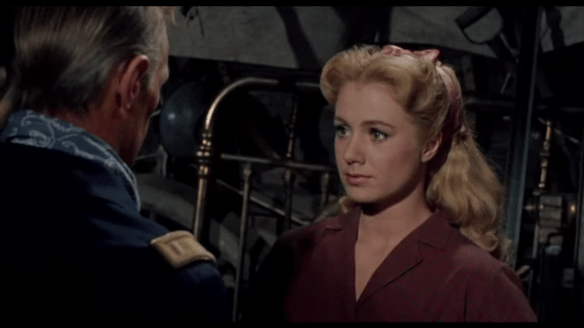

Time passes and Pierre grants the ambitious woman to set up shop in his laboratory, tucked away in a shabby little corner. Once more she jumps at the chance, seeing the space, completely devoid of any sort of facilities, as the perfect proofing ground for her ideas.

She immediately leaves an impression on the youthful lab assistant (Robert Walker). However, it’s her inexhaustible work in radiation that leads Pierre to revere her. Because over time he grows accustomed to her, at least in a professional sense. While shrugging off her graduation initially, he finds himself making an appearance all the same. He’s compelled to.

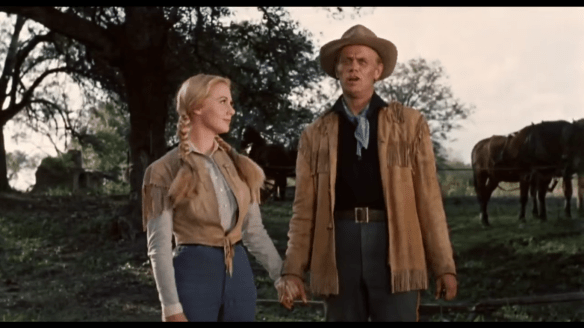

The next course of action is his hesitant invitation on a weekend away, and she gladly accepts, meeting his parents out in the country over croquet, including an uncharacteristically bristly Henry Travers playing the elder Curie. The budding romance is obvious, and it’s convenient for our stars.

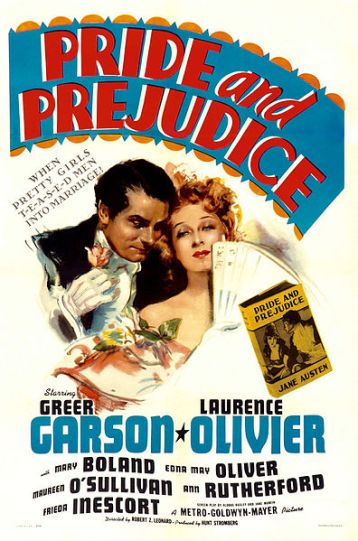

Mervyn LeRoy’s film, on the whole, is a lightweight, cordial biography working loosely with facts to draw up the life of Madame Curie and her future husband. It’s just as much a vehicle for the lasting chemistry of Garson and Pidgeon as it is an ode to one of the most renowned scientists of the turn-of-the-century. While I’m not exactly the most gifted empiricist, even I am aware of the substantial shadow the Curie name casts over the discipline. In some small manner, this movie allows them to be appreciated and palatable for a mainstream audience, albeit an audience of wartime viewers.

Even this admission is telling, suggesting this tale of romance and biography functions as a bit of timeless morale boosting. It showcases love and the triumph of the human spirit, even in the face of bitter tragedy. Still, it does not immediately signal propaganda like Mrs. Miniver or other such entries. This might be to its benefit.

Taking everything into account, what makes it rather extraordinary is Garson’s heroine because certainly, Marie Curie is well-deserving of a biographical treatment and in an age where women were kept out of such positions, she provides a paradigmatic example for future generations. (No one can rebuff her two Nobel Prizes!)

Both her work and her career are important to her. The same goes for her future husband. But even with their work as a constant distraction, they realize in between the long lab sessions, living life without one another would leave a void. Beyond this, their work would be far less meaningful. In his rather roundabout manner, Pierre professes his need for her, comparing their marriage to NaCl. It’s not exactly romantic to be table salt, but they work well together, and they do form a solid union.

While the scientific jargon, filled with chemical elements, feels a bit clunky, it’s admittedly difficult to figure out a way to make their regimen of uranium-based experiments riveting. The major takeaway is the uphill push for funding since Curie is dismissed on all sides, not only based on her unprecedented research, but also for the arbitrary fact, she’s the opposite sex of every stodgy member of the scientific board.

Not to be daunted, the couple sets up business in a shack, and the Curies take on the task with their usual tenacity, their sole objective: separating barium from radium. This is Madame Curie in its stagnant phase and yet no one can doubt Greer Garson’s candor. One is reminded of the crushing moment she thinks the radium has all but evaporated and with it four years of toil. She’s nearly inconsolable.

Then, when their success is finally validated, she’s looking into her husband’s eyes and commending him as a great man, not by the standards of the world, but due to his kindness, gentleness, and wisdom. It’s a striking moment because this is no doubt her story, but as with any union, it takes two people to make it work.

But she subsequently has another sublime moment of indescribable vulnerability, pained to her core by the most grievous loss of her life thus far. She is a woman of science and of great intellect, but the service Garson does for Curie (authentic or not) is making her all the more human at her lowest point.

The final verdict remains that Madame Curie is an unimaginative bit of hagiography, but for the faithful fans of Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon, it is another fitting eulogy to their joint talents. For some, this might be enough to charitably see past what flaws there are.

3/5 Stars