“In this job you either end up poor or riddled with bullets.” – Jean-Paul Belmondo

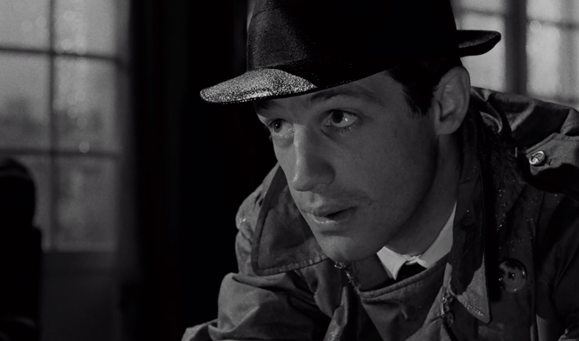

Director Jean-Pierre Melville has an impeccable gift for taking the most mundane actions and behaviors and making them so compelling. In the opening notes of Le Doulos, we have an ordinary man strolling across a sidewalk, under an overpass, feet clacking on the pavement. The music rages behind him, as he’s enveloped in shadow and the title credits.

Melville readily leans into his penchant for gangsterism and Hollywood pulp introducing this man with a fedora and trenchcoat. They are an extension of each of his players. Just as each frame is equally tinged with the somber detachment readily available in any of his films. Because the characters are always products of their environment, incubated and cultivated by the writer-director, in the same way; their dress is an extension of their identity.

Le Doulos itself derives from a slang term for a type of “hat,” a police informant. The stoolie, of course, is one of the age-old cretins right up there with traitors and child molesters. No one has any pity for such a miserable excuse for a human being. Conventional wisdom dictates they deserve to be kicked out into the gutter or locked away with the rest of the animals.

Except in some sense, Melville’s picture isn’t making this sort of ready-made statement. There is more to his small-time criminal types, facilitated by a complex plot and nuanced characters. It comes down to the old quandary of honor among thieves. What does human nature have to tell us when wealth and women are involved?

In this particular story, Maurice is a recently paroled thief and as is often the case, he’s already got his next crime in the works. It’s a safe-cracking job involving a former accomplice named Silien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) and one other party.

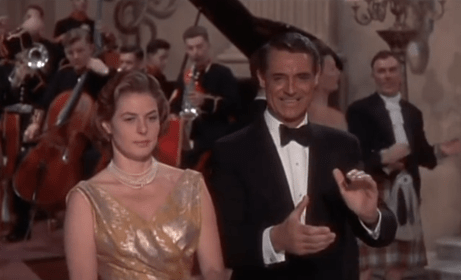

For being the lead, Belmondo takes some time to integrate into the story, eventually paying a house call on Maurice and his lady friend Therese. And yet from his first entrance, he takes to the environment like a fish to water. If Alain Delon helped develop the aesthetic of Melville, Belmondo deserves a prominent place as well. They both make compelling criminals because their charisma is irrefutable.

For me, a defining moment for the Belmondo persona was standing outside the movie house mimicking the tough guy iconography of Humphrey Bogart in Breathless (1960) because for French cinema he was at home in the same world and thus, there was hardly a more suitable partner in crime, as it were, than Melville.

One cannot say he’s carved out of the same block as Bogey. He’s impudent even a bit scrawny, but there’s nevertheless, a rogue charm to him. Handsome in a way that assumes the complete antithesis of a classical matinee idol.

I couldn’t help but think how quaint and simple petty theft was to commit in the old days. That is, until it isn’t. There’s nothing elaborate about the blue-collar crime, in fact, it’s a banal safe cracking job. We know not if there’s even any payoff worth noting. However, even this scenario gets botched when other gangsters come on the scene.

One cannot help but think of Band a Parte – made the following year — as Godard famously counted Melville among his idols, even giving him a small role in Breathless. He subsequently took his advice on how to edit the picture, hence the birth of his famous jump cuts.

At first, I assumed this latest wrinkle was the police being tipped off, but that would make our title too easy. This is not Melville. We must constantly revise our opinions of our central protagonists. As is, it feels as if the film might be climaxing about an hour too early. How will there ever be a story out of what’s left to talk about? And yet Le Doulos stays true to form by analyzing such a stooge in his natural habitat.

Instead, he lets one criminal bleed out and another one get it in the gut from Maurice’s pistol. All of a sudden, more prison time seems an all-too-likely possibility as he sweats it out. This is where Belmondo shines, playing all sides, as a perceptive wheeler-dealer working both angles on the cops and robbers.

Silien is openly accommodating to the police, including their hard-bitten chief (Jean Desailly). When they look to question him at the station — a wonderfully blocked sequence with nary a cut — a normally bland and subpar scenario we have to live with, is made far more compelling.

The informant begins his obligatory rounds including a visit to a gambling house. It’s a quintessential Melville moment as he follows the fedora through hatcheck as one of the blatant symbols at the core of his picture, as worn by Belmondo, in particular. It is his marker just as guns and trench coats are also some of Melville’s directorial calling cards.

Then Michel Piccoli walks through the side-door of the nightclub. Perhaps he’s the key. And yet it’s not him, just as it’s not the three female characters who are all pawns — not only compliant accomplices to the male lovers in their lives — but mechanisms of the director to move the story.

It would sound overly harsh if most, if not all, of Melville’s characters were not also relayed to us in this fashion. Even this severity somehow fits the world and conveniently functions for the sake of the story.

What becomes evident is just how convoluted Le Doulos is, which is especially surprising for a French film but, of course, this is another fitting hallmark borrowed from American noir. Melville employs several expositional scenes and even some flashbacks, in order to fill in some ambiguities in the story thus far.

By the time we reach the finale and the final steps of this picture, there is a satisfying if fatalistic weight to the dramatic situation. The abysmally rain-drenched ending is also immersive cinema at its finest.

Because what is a gangster picture if not marred by some dark current of tragedy? Belmondo is not what we believed him to be and yet in the natural order, he cannot be allowed to exist. Fate has not allowed for it. Fittingly, his final act is to straighten his fedora in the mirror one last time. Bogart would have been proud. He went out an unequivocal anti-hero.

4/5 Stars