In adolescence, you are inundated with stories about dogs. The Red Fern Grows, Shiloh, Homeward Bound, Ginger Pie, Marmaduke, Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Air Bud, Snoopy, and Old Yeller. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg, off the top of my head. Sounder belongs to the same storied tradition based on humanity’s infatuation with canines which is certainly well-founded.

Except some will be surprised to find that this Depression-era tale brought to us by Martin Ritt is hardly about a dog at all. True, we are met with the eponymous hound dog right off the bat. What greets our ears is the bouncy staccato harmonica-twanging behind the visuals of a frantic tear through the underbrush that goes with the territory of a coon hunt. It’s an instantly recognizable image to introduce our characters.

Not just Sounder but a boy named Henry Lee and his father, the jovial but hardpressed Nathan. The year is 1933 and we’re in Lousiana in the midst of the Depression. With society sectioned off as it is, as a black family, the Lee’s have been forced to scuttle through by sharecropping for a white farmer. It’s the fate faced many African-American families of the day.

They’re perpetually in debt, have trouble keeping food on the table, and live with the most meager means possible. All in all, with two parents, Nathan and his wife Rebecca (Cicely Tyson in a fiercely unvarnished performance), there are also three kids, and of course, Sounder. Writer Lonne Elder III takes this atmosphere, the environment, and the family living within it and builds the framework of a story with great care and concern for their everyday reality. The plights and the joy that they still manage to have.

Taj Mahal, while also providing the film’s music, does a fair number in front of the camera as well as the energetic neighbor named Ike who drifts in and out of the story as he pleases. There are baseball games where Nathan Lee comes out the hero striking out his last opponent with runners in scoring position. From the local church, you can hear Gospel spirituals like “Old Time Religion” ringing out with fervor.

But in the same community, there’s a segregated schoolhouse and Nathan gets jailed and sent away for a year of hard labor for what seems like a trivial infraction. White men, including the local sheriff and the shopkeeper, will hardly budge an inch for a black man. That’s what seems so pernicious. Sometimes it’s not even outright violence but it’s this inability to change or have any amount of grace or understanding. There is no clemency to be had based on this rigid narrowmindedness.

When you begin watching more movies sometimes you fail to acknowledge those that are unpretentious and good-natured — the kind of stories that are meant for the whole family and wholly uplifting to the soul. Sounder is one of those movies. Surely there was a social hierarchy in place of oppression and de facto segregation. And yet around the nucleus of the family, there is a decency that pervades the picture and ultimately lifts it up. While it doesn’t completely eradicate ill-will, it does push it to the fringes of the frame.

Family reunions have never been so poignant — considering the moment where Nathan finally comes home after innumerable trials and his family has toiled and sweated day after day to hold onto their land. What they have in that instant is a small slice of heaven. It’s written over every face as the space between them rapidly fades away and they meet in an embrace that brings their world back together as it was meant to be.

But Sounder also manages to be a tale of empowerment for one lad in particular, young Henry Lee. The movie places people in his life who are willing to give him a leg up. There’s old Mrs. Boatright who is one of the few whites who will take any kind of stand — even a slight one — and she blesses him with things like The Three Musketeers.

It’s these people and books and knowledge that give a glimpse to a world of greater freedom and opportunity. An avenue to a life where people cannot keep you down no matter how hard they try because with ideas comes a power to think and to be your own person, set on improving yourself and the world as you go forward.

Yet another woman, a schoolteacher, takes an interest in Henry Lees improvement since she perceives the quiet wisdom that can be cultivated into something fully-realized. Her gift to him comes through education and elucidating him about figures like Harriet Tubman, Crispus Attucks, and W.E.B. Dubois — people who were shapers of history big and small — just as he has the opportunity to be.

Granted, it does feel as if the family’s pet is pushed to the periphery for much of the film, but in a way, it feels like a realistic depiction. He doesn’t need to be front and center. By their nature, if dogs are really man’s best friend, what makes them so meaningful has to do with their loyalty — they are always there — consistently reliable.

Because the life of an impoverished family like the Lees is the epitome of hardship. They need all the stability they can get. You will come to realize it is not really about a dog at all and certainly not one of those family-friendly films marketed as such because they feature some extraordinary, nearly superhuman animal.

No, Sounder is for the family because it takes care in documenting the realities of this particular family in a way that is thoroughly candid. It might still stand as faulty advertising but for the plethora of folks who are moved by the movie, they probably won’t be complaining when the credits roll. What we get is far better than a run-of-the-mill boy and his dog narrative. What I am reminded of is one subtle parallel. Sounder is winged by a shotgun when Nathan is taken away. He doesn’t come back for a long time. But when his wounds are healed, he returns good as new. There’s a startling resilience present in both the canine and the family.

4/5 Stars

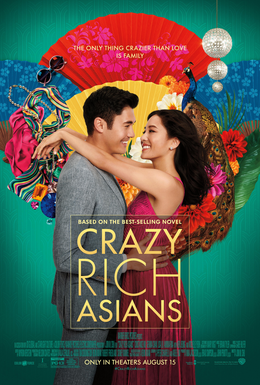

The opening gambit of Crazy Rich Asians feels like the scene some Asian moviegoers have been waiting for all their lives. We’re in a stuffy hotel lobby with the snooty staff looking to deny service to Eleanor Sung-Young (Michelle Yeoh) and by the end of the conversation she winds up mopping the floor with them. It’s satisfying to get some sweet revenge but short of being malicious, it’s rewarding, setting the tone for the rest of the experience to come.

The opening gambit of Crazy Rich Asians feels like the scene some Asian moviegoers have been waiting for all their lives. We’re in a stuffy hotel lobby with the snooty staff looking to deny service to Eleanor Sung-Young (Michelle Yeoh) and by the end of the conversation she winds up mopping the floor with them. It’s satisfying to get some sweet revenge but short of being malicious, it’s rewarding, setting the tone for the rest of the experience to come. Tom Cruise is the closest thing we have to a modern marvel on the current cinema landscape. Despite being over 50 years old, it seems like he continues to redefine what it means to be an action hero in the 21st century. A lot of his brilliance stems from taking a page out of the playbook from generations gone by.

Tom Cruise is the closest thing we have to a modern marvel on the current cinema landscape. Despite being over 50 years old, it seems like he continues to redefine what it means to be an action hero in the 21st century. A lot of his brilliance stems from taking a page out of the playbook from generations gone by.