Classic Hollywood musicals usually have a very common framework that they rarely seem to deviate from. There’s almost an accepted unwritten rule that they will function like so. Typically, there is an overarching story being told and yet the narrative is conveniently broken up by song and dance routines that not only provide immeasurable entertainment value and give an excuse for talented performers to strut their stuff but also serve to move our movie forward comedically, romantically, dramatically, whatever it may be.

Classic Hollywood musicals usually have a very common framework that they rarely seem to deviate from. There’s almost an accepted unwritten rule that they will function like so. Typically, there is an overarching story being told and yet the narrative is conveniently broken up by song and dance routines that not only provide immeasurable entertainment value and give an excuse for talented performers to strut their stuff but also serve to move our movie forward comedically, romantically, dramatically, whatever it may be.

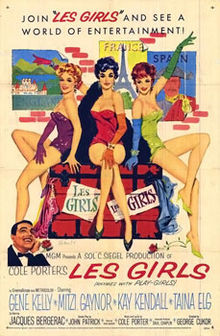

Thus, Les Girls is a generally absorbing musical simply in terms of its mechanics. They stray slightly from the set formula. It’s a bit of a Rashomon (1950) plotting device. If you will recall, Akira Kurosawa’s film famously told the same turn of events three times over from three differing perspectives. That’s what happens here, in a sense, with the action being set partially in a courtroom (a first for a musical) and then the rest on the road with theater performers.

It all comes into being because of a libel suit that has broken out between two former colleagues who used to be a part of Barry Nichols’ Les Girls act that was a smashing success in its day. But following the publishing of a tell-all memoir and suggestion of a supposed suicide attempt, blood is boiling between Frenchwoman Angele Ducros (Taina Elg) and British-born Sybil Wren (Kay Kendall) who had the gall to publish such a story.

Of course, there are actually three ladies in question, the third being the peppy American Joy Henderson (Mitzi Gaynor) who rounds out the act and, of course, Barry finds himself romantically linked to each one though he specifically makes a habit of never falling in love with his fellow dancers. It proves a hard rule for him to keep but for the audience, it gives us a good excuse to see Gene Kelly share at least one moment on the dance floor with each of his talented costars individually.

This proved to be the final film score of America’s beloved songsmith Cole Porter and he provides a few moderately memorable numbers including the title track. Kay Kendall is thoroughly convivial to watch as a comedienne and performer throughout with her number “You’re Just Too, Too” being one of the most playful in the picture.

Meanwhile, the final number with Kelly and Gaynor is a blast full of romance around table and chairs. But the real kicker is feisty Mitzi Gaynor letting Kelly have it over the head with a picture frame, deservedly so, I might add. But in the end it all comes to naught, the court case is dropped and we are left with an open ending that’s winking at us. At least everyone’s happy.

Though he is not often remembered as a musical director, in some sense, George Cukor seems well within his element with the material at hand always adept at bringing together stories of behind the scenes antics and goings on between women and their men. That’s precisely what we have here.

This would prove to be Gene Kelly’s final film with MGM after an illustrious run. You also get the sense that perhaps this character is closer to the real Gene Kelly — the man who was constantly called a perfectionist and recounted later by Esther Williams to be a terror to work with. And here he still has a dose of his winning charm but there are also signs of that dancing slave driver working his girls to the bone and unwittingly romancing them at the same time. Still, there’s no doubting his inspired screen presence that underlines nearly every picture he was ever in.

It’s true that a previous iteration of the film was to have included Cyd Charisse, Leslie Caron, and Jean Simmons. That would have been an interesting combination to be sure but what we got here instead is still a stunning and at times thoroughly unconventional musical.

3.5/5 Stars

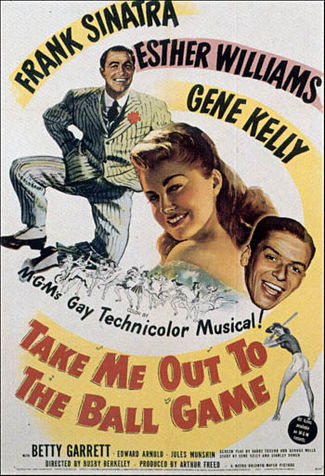

There’s something perfectly in sync between Gene Kelly and Donald O’Connor so I could never choose another duo over them but Kelly and Frank Sinatra are such wonderful entertainers that they help make this period baseball number a real musical classic even if it has to fall in line behind a row of other quality contenders.

There’s something perfectly in sync between Gene Kelly and Donald O’Connor so I could never choose another duo over them but Kelly and Frank Sinatra are such wonderful entertainers that they help make this period baseball number a real musical classic even if it has to fall in line behind a row of other quality contenders.

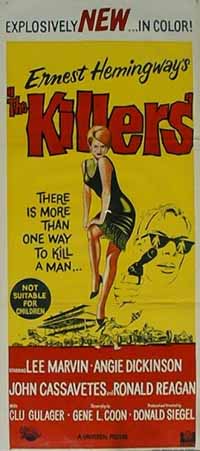

After an opening to rival the original film noir The Killers (1946), though nowhere near as atmospheric, Don Siegel’s The Killers asserts itself as a real rough and tumble operation with surprisingly frank violence. However, it might be expected from such a veteran action director on his way to making Dirty Harry (1971) with Clint Eastwood.

After an opening to rival the original film noir The Killers (1946), though nowhere near as atmospheric, Don Siegel’s The Killers asserts itself as a real rough and tumble operation with surprisingly frank violence. However, it might be expected from such a veteran action director on his way to making Dirty Harry (1971) with Clint Eastwood. We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams

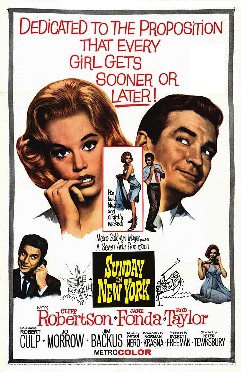

We’re all part monsters in our subconscious. ~ Leslie Nielsen as Commander Adams It would appear that a film like Sunday in New York would never exist today. First, it’s obviously rooted in a stage play and it functions with the kind of moments you might expect out of some of Neil Simon’s works around New York though this particular story was crafted from a play by longtime screenwriter Norman Krasna who wrote many a screwball comedy back in the day.

It would appear that a film like Sunday in New York would never exist today. First, it’s obviously rooted in a stage play and it functions with the kind of moments you might expect out of some of Neil Simon’s works around New York though this particular story was crafted from a play by longtime screenwriter Norman Krasna who wrote many a screwball comedy back in the day. Anime is very much a Japanese art form denoted by its style, the visuals, and even the depiction of its characters with wide eyes all the better to convey emotions. Oftentimes the images onscreen are a great deal more stagnant than the real-time action that American animators try and replicate with a greater frame rate.

Anime is very much a Japanese art form denoted by its style, the visuals, and even the depiction of its characters with wide eyes all the better to convey emotions. Oftentimes the images onscreen are a great deal more stagnant than the real-time action that American animators try and replicate with a greater frame rate. Juzo Itami’s so-called ramen western Tampopo is unequivocably original in its hilarity, opening with what could best be called a public service announcement. A suave gangster is getting ready for the movie screening only to be disrupted by a noisy bag of curry potato chips. He threatens the foodie and sits back down to enjoy the entertainment, concluding the film within a film.

Juzo Itami’s so-called ramen western Tampopo is unequivocably original in its hilarity, opening with what could best be called a public service announcement. A suave gangster is getting ready for the movie screening only to be disrupted by a noisy bag of curry potato chips. He threatens the foodie and sits back down to enjoy the entertainment, concluding the film within a film. Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) were two films that took a fairly extensive look at what a chain gang actually was in cinematic terms. Meanwhile, Sam Cooke’s eponymous song made almost in jest has added another layer to the tradition.

Sullivan’s Travels (1941) and Cool Hand Luke (1967) were two films that took a fairly extensive look at what a chain gang actually was in cinematic terms. Meanwhile, Sam Cooke’s eponymous song made almost in jest has added another layer to the tradition.