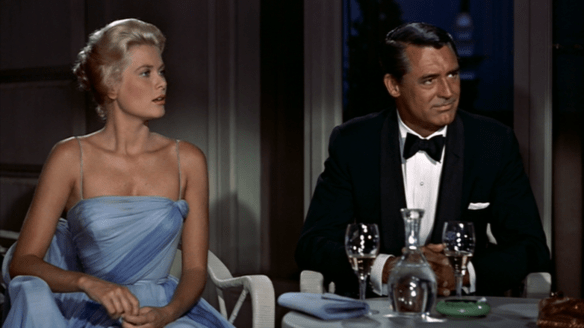

There are such a vast number of levels to appreciate Rear Window on and one of those is its impeccable use of sound as well as a score courtesy of Franz Waxman. In fact, it is quite easy to consider it as a film with a wholly diegetic soundtrack but it’s really a complicated weaving of sound orchestration playing against the images onscreen. For instance, against the credits, as the blinds come up, we’re met with the playfully cool jazzy beats of “Prelude and Radio” which proves to be in perfect juxtaposition with the deathly hot heatwave hitting Greenwich Village in the film’s opening moments.

We’re also inundated with all types of songs popular and otherwise which can be picked out of the story organically if you’re paying attention. Two of the most obvious additions are “That’s Amore” and then “Mona Lisa” which can be heard being sung by a group of party guests.

Whether or not it’s a slight nod to our heroine Lisa is up for debate but it’s also notable that she, in essence, receives her own theme song which is concurrently composed by the songwriter who lives in the courtyard that we come to know over the course of the film. It slowly involves from its nascent stages into a full-fledged tune that gains its wings once the romance between Lisa and our protagonist L.B. Jefferies has come into its own.

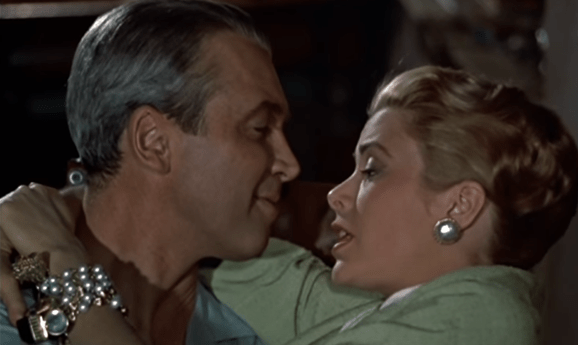

Obviously, beyond the elements of soundtrack Rear Window develops so immersive a world and Hitchcock expertly inserts us directly into the environment to the extent that we have no choice but to become involved in the whole ordeal. We are accomplices, if you will, in this viewing party of Jimmy Stewart’s.

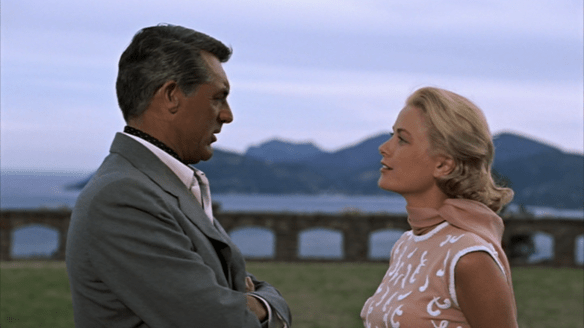

It truly is an exhibition in the moving image because the film works so brilliantly with them. Certainly, it begins with the staging and the complex setup Hitchcock had to work with at Paramount Studios but there’s simultaneously the use of color cinematography, the lighting of the stages which sets the scene given the time of day, and common street noise that lends an almost imperceptible authenticity that we take for granted.

Furthermore, working with his long trusted photographer Robert Burks you see Hitchcock moving so fluidly and with so much purpose through the playground provided him. The camera captures objects with clear intention and a crispness that far from simply giving us the illusion of being in the space, in many ways, makes us feel like we are actually right there with Stewart looking out into the courtyard.

You also get the true essence of what visual filmmaking is because his powers of suggestion and even persuasion of the audience are impressed upon us by what he deems important. Hitchcock lays out nearly all of Stewart’s backstory not with clunky expositional dialogue but by giving us a wordless parade of his apartment while our protagonist sleeps. And the whole picture is a constant rhythmic cadence of being fed images followed by Stewart’s reaction shots. It’s Film at its primacy. Where two images put together are blessed with so much more meaning and suggestion than they could ever have alone.

But far from simply marveling at what Hitch has accomplished it’s far more miraculous that we become so enveloped in this story. It’s an admirable mystery plot chock full of tension that’s built up over time and successive shifts in perception, time of day, and personnel moving in and out of the complex. Our one commonality is Stewart stuck in that wheelchair with only his broken leg, his camera, and the neighbors to keep him entertained. They do far more than that.

Rear Window’s A-Plot is a perplexing mystery thriller that we watch unfold with a systematic unraveling that’s unnerving in part because Hitchcock has orchestrated it all in a limited space. Furthermore, he has handicapped his protagonist and the outsiders coming in are constantly causing us to second guess or reevaluate our assumptions be they the insurance agency nurse Stella, Jefferies’ policeman pal, or his best girl Lisa. Each character is at one point in opposition to Jefferies while also providing a sounding board for his cockamamie theories which start to bear the grain of truth. We get to be a part of it all.

The utter irony is that once more not only is Hitchcock’s villain atypical — in nearly all areas a seemingly unspectacular man — he’s also quite overtly styled after David O. Selznick. If you know anything about the producer he shares some resemblance with Raymond Burr and there’s no denying that Hitchcock was never fond of the other’s meddling. As much as I love the Rebeccas (1940) and his earlier American works if Rear Window was a representation of the hands-off approach to his filmmaking than I would have to side with him.

At least by this point in his career, there’s no denying that he projected a singular vision that could hardly be quelled by any individual. This is “Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window,” after all, as the opening credits proclaim.

However, the beauty of this picture is that it truly does stand up to multiple viewings and every repeated viewing offers up new depths or at least minor revelations that add an even greater relish to the experience.

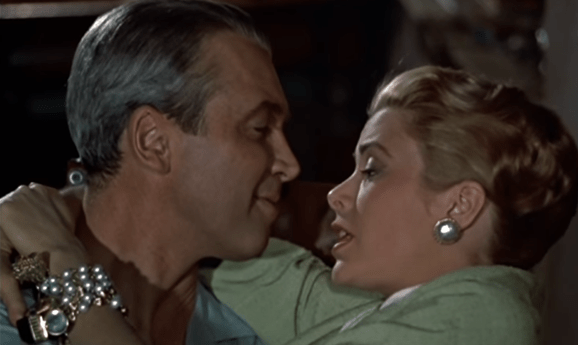

In particular, are the underlining themes of romance. Because this is a film about love in all its many facets with each character or couple reflecting a certain permutation of what romantic love looks like.

The love stories are playing out in each compartment of the apartment complex. Miss Torso, the queen bee with the pick of the drones. She’s very much eye candy but in the final frames, we realize there’s more to her as her love comes back home from the army. There’s Miss Lonelyhearts who is desperately seeking love and yet has enough respect not to stoop below her dignity. It’s a song that lifts her out of her despair. The Newlyweds are still in the honeymoon phase and we never see them.

Meanwhile, you have Stella providing her homespun philosophy that people shouldn’t overanalyze their situation. Jefferies is pushing back against any serious romance because in his estimation Lisa is far too perfect for him. Meanwhile, Lisa is left believing she can live in any world that Jeff is in. The list goes on and on.

But for the threads to be resolved that must become fully intertwined with the murder at its core because such an event calls for a response from our characters — at least our main ones. When Lisa sacrifices so much to show her love and devotion to him, he realizes how much he misjudged her character and perhaps more profoundly how dearly he loves her and never wants to lose her. He has made the transition from armchair philosopher and misanthrope to a man smitten with someone else. As long as he ditches the window watching he should be fine.

That leads us to another area of discussion. There’s a bit of a moral commentary present though Hitchcock doesn’t seem all that interested in those conclusions per se as much as he likes manipulating them for the sake of his drama. And yet like Vertigo four years later there is this unnerving sense that he is tapping into some of humanity’s darkest desires to watch and spy on others for pleasure without any consequence or any vulnerability on the part of the peeper.

That draws me to another aspect of the film that I’ve never really considered. Rear Window implicitly asks what it is to be a neighbor or at least what it is to live with neighbors. There’s very little in the realm of actual judgments except for the small condemnation that comes from the woman who lives just above the murderer after her yippy dog has been killed. What does she say?

You don’t know the meaning of the word ‘neighbors’! Neighbors like each other, speak to each other, care if somebody lives or dies! BUT NONE OF YOU DO.

What she provides is a heartfelt and searing indictment which is nevertheless lost in all the commotion whether it’s the big party going on across the way or the realization by our heroes that their theories about murder have been confirmed. It did make me consider even briefly if the so-called Great Commandment is to “Love Thy Neighbor,” what does that look like?

Far from peering in at other people and staying anonymous, it seems like it involves reaching out to others. In some ways, being vulnerable and candid — transparent even — so others feel comfortable entering into our lives. Like Stella says sometimes people need to go on the outside and look in for a change. If nothing else that breeds empathy.

Of course, if that was the case, there would probably have been no murder and that’s what we want right? Well, anyways, Rear Window still stands as my favorite Hitchcock picture and one of the most clinical and compelling thrillers of all time. But you probably already knew that. If you did not I implore you to break both your legs if need be and go lock yourself in a room and force yourself to watch it right this minute.

5/5 Stars

Sabotage: Willful destruction of buildings or machinery with the object of alarming a group of persons or inspiring public uneasiness.

Sabotage: Willful destruction of buildings or machinery with the object of alarming a group of persons or inspiring public uneasiness.