Just a day ago a whole slew of individuals shared their 5 Favorite Films of the 1950s for National Classic Movie Day. Thank you again to The Film & TV Cafe for spearheading that quality endeavor!

In retrospect, I realized all my choices were really “A Pictures,” which were difficult and yet at the same time fairly easy to choose. They were all no-brainer picks because I love them a great deal. Many others also chose the likes of Singin’ in The Rain, Roman Holiday, and Rear Window (for good reason, I might add).

However, the decisions that left me the most intrigued were, of course, the dark horses and the underappreciated gems. Certainly, you have to start somewhere when it comes to embarking on the classic movie journey, but half of the fun is unearthing treasures along the way. For instance, I was left charmed by the following picks, all wonderful films in their own right, that I would have never thought to choose:

People Will Talk, The Narrow Margin, The Earrings of Madame De…, It’s Always Fair Weather, The Burmese Harp, and Night of the Demon, just to name a handful.

All of this to say, I was inspired by these folks to take on “Round 2” for my own edification. I’m going to leave my highly subjective list of “A Sides” behind for what I’ll term the “B Sides.” The only rule I’m going to place on myself is that this fresh set of picks must be what I deem to be “underrated movies.” Again, it’s a very subjective term, I know.

Regardless, here they are with only minor deliberation!

Stars in My Crown (1950)

Jacques Tourneur is an unsung auteur and if all he had on his resume were Cat People (1942) and Out of The Past (1947), his would be quite the legacy. However, throughout the ’50s, he helmed a bevy of fabulous westerns and adventure pictures. I almost chose Wichita (1955), also starring Joel McCrea. In the end, this moving portrait of a frontier minister won out because it cultivates such a fine picture of how one is supposed to live in the midst of a bustling community of disparate individuals. This involves conflict, tension, tragedy, and ultimately, a great deal of human kindness.

The Breaking Point (1950)

Howard Hawks’s To Have and Have Not with Bogey and Bacall is probably more well-known but this version has merits of its own. Namely, a typically tenacious and compelling John Garfield playing a returning G.I. and family man trying to make a living in an unfeeling world. His wife portrayed by Phyllis Thaxter deserves a nod as well for her thoroughly honest effort. The movie gets bonus points for shooting in and around my old summer stomping grounds on Balboa Island.

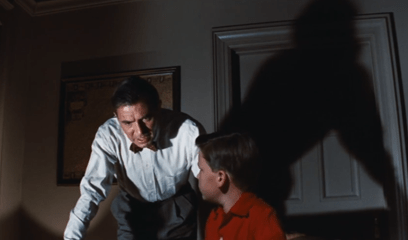

Bigger Than Life (1956)

It does feel a bit like Nicholas Ray was the king of the 1950s. Rebel Without a Cause is the landmark thanks, in part, to James Dean. However, his best picture, on any given day, could be Johnny Guitar with Joan Crawford, On Dangerous Ground with Robert Ryan, or The Lusty Men with Robert Mitchum. Today I choose Bigger Than Life because James Mason gives, arguably, the performance of his career as a man turned maniacal by the effects of his new miracle drug, cortisone. It employs the same gorgeous Technicolor tones and Cinemascope Ray would become renowned for while also developing a truly terrifying portrait of 1950s suburbia.

Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

I skipped James Dean’s most famous film, but never fear because in his place is a film featuring an actor who channeled the American icon’s angsty cool. In Andrzej Wajda’s Polish drama, set at the end of WWII, Zbigniew Cybulski embodies much of the same electric energy. His defining performance is central to a gripping tale about a country absolutely decimated by war, between German occupation and the ensuing columns of Russian soldiers arriving on their doorstep.

Good Morning (1959)

This might be my personal favorite of the Yasujiro Ozu’s films for its pure levity. The images are meticulously staged as per usual with glorious coloring. Every frame could easily be a painting. However, against this backdrop is a domestic story about two brothers who hope to wage a pouting war against their parents who won’t cave and buy them a TV like they want. The conceit is simple but the results are absolutely delightful.

Well, that just about wraps up my 5 supplemental picks…

Except I would be remiss if I didn’t share at least a handful of other outliers. Let me know what you think of the films I chose!

Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble holds a meta quality that still somehow feels radically different than Godard or Truffaut’s turns in Contempt and Day for Night. It attempts to channel a younger point of view — that of an ambitious student — with an overtly political agenda. Agnieszka is an independent, fiery individual intent on making her thesis the way she sees fit. She’s prepared to go digging around in uncharted territory or at least in territory that has been off limits for a long time. That understandably unnerves her adviser and still, she forges on.

Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble holds a meta quality that still somehow feels radically different than Godard or Truffaut’s turns in Contempt and Day for Night. It attempts to channel a younger point of view — that of an ambitious student — with an overtly political agenda. Agnieszka is an independent, fiery individual intent on making her thesis the way she sees fit. She’s prepared to go digging around in uncharted territory or at least in territory that has been off limits for a long time. That understandably unnerves her adviser and still, she forges on. Everywhere she goes Agnieszka drags along her crew who utilize handheld cameras and wide-angle lenses, at her behest, just like American films. It becomes obvious that Birkut was hardly a political figure, instead contenting himself by using his hands to lay breaks and lay them well. He takes pleasure in his work with a big sloppy grin almost always plastered on his face. It was people like him who made Nowa Huta into the great city of industry that it was, and he became an emblem of that. The party monumentalized him and he became the man of marble to be lauded by all.

Everywhere she goes Agnieszka drags along her crew who utilize handheld cameras and wide-angle lenses, at her behest, just like American films. It becomes obvious that Birkut was hardly a political figure, instead contenting himself by using his hands to lay breaks and lay them well. He takes pleasure in his work with a big sloppy grin almost always plastered on his face. It was people like him who made Nowa Huta into the great city of industry that it was, and he became an emblem of that. The party monumentalized him and he became the man of marble to be lauded by all. We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response.

We’re used to getting our hands dirty in the thick of World War II, whether it is in the European theater or the Pacific, but very rarely do we consider the consequences that come in the wake of such an earth-shattering event. Things do not end just like that. There must be periods of rebuilding and rehabilitation. There is unrest and upheaval as the world continues to groan in response. There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.

There are love scenes that are quiet, subdued, and truly intimate. In fact, it feels rather like Hiroshima Mon Amour where the camera lingers so closely on two figures in such close proximity. There does not have to be great movement or dramatic interludes because having two people next to each other should be enough. The historical context in itself seems to be enough. For that film, it meant Japan post-1945. For this one, it’s Poland after the clouds of war have lifted.