Mr. Arkadin (also known as Confidential Report) has the abundance of canted angles and striking visual flourishes one usually attributes to the films of Orson Welles. It also boasts his ever more disorienting sense of space and shot-reverse-shot even as the international cast, financing, and locales outside the prying eyes of Hollywood map his labyrinthian journey to continue making movies.

His entry into this particular story is a small-time smuggler, Guy Van Stratten. There’s something abrasive and unplaceable about Robert Arden. It’s rather like when non-English-speaking filmmakers will cast an American, and it sounds tone-deaf in a picture that otherwise feels normal. Regardless, he receives a tip-off from a dying man, and it sends him in search of something…

Arkadin, an aristocratic Russian, as played by Welles, is really another version of Harry Lime from The Third Man with everyone talking about him and wanting to meet him as he remains just out of reach and hidden behind a mask at a masquerade party.

Stratten has ambitions to get in with the daughter of the enigmatic Arkadin. Welles casts his wife Paola Mori to play his carefree young daughter (albeit dubbed). In the end, the gruff answer-seeker winds up globetrotting after Arkadin, hired by the man himself to see if he can dig up any dirt on him. It feels like the ultimate act of paranoia if in fact a double-cross isn’t in order.

While his accomplice Mily (Patricia Medina) is out on her own, he crosses paths with the likes of Michael Redgrave, an eccentric pawnbroker providing some leads, and then Akim Tamiroff who is also somehow implicated in a web of conspiracy.

Plot notwithstanding, Mr. Arkadin feels increasingly emblematic of what Welles’s cinema became after his earlier successes. He was scrounging around for funding, cobbling together films all across Europe with a cadre of international talent, and increasingly drastic creative choices.

It’s evident in a picture like The Other Side of the Wind generations later, which historically took years to be completed long after Welles’s death. It does feel like every subsequent picture after Kane continued to be a monumental struggle, and it’s some small marvel that each one got made for any number of reasons. Add Mr. Arkadin to the list.

It’s not explicitly Shakespearian, but it has a certain gravitas blended with the cheap smuttiness of noir street corners and pulp novels. We are treated to a Wellesian Christmas party. The focal point is a rather perturbing visual carousel full of jocund gaiety and lurking menace capped off by a band playing “Silent Night.”

Ask me to say exactly what we’ve watched with all the various plot details, and I don’t dare try. But it bears the markers of Welles, full of flourishes and at one time both mystifying and inexorable. It’s easy to criticize the flaws, but Orson Welles hardly makes mediocre pictures. There’s always a gloriously messy vision behind them. It’s the same with Mr. Arkadin.

3.5/5 Stars

Compulsion (1959)

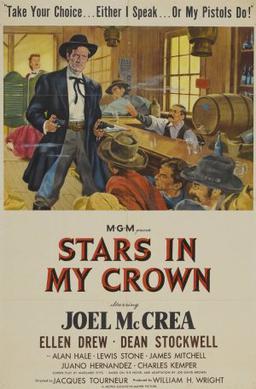

I never thought about it much until his passing but there’s something about Dean Stockwell in his young adult years and even his later roles that’s reminiscent of James Dean. He’s not emotive in the same way as the method actors; he’s a button-upped clean-cut version with his own neuroses.

They have some facial similarities, true, but it comes down to something more difficult to pin down when it comes to actors, whether eccentricities or the bits of business that draw in your gaze so you can’t help but watch them at work. With Stockwell, it’s something he was able to draw upon later in his career when he had a reemergence and a renaissance; acting seemed fun again.

In 1959, James Dean was gone for a few years already and Stockwell was still closer to the beginning of his career than the end. He plays one two young men who have read too much about Nietzsche’s superman believing themselves to be above the law.

Bradford Gilman is his counterpart a disingenuous sociopath who knows how to throw his charisma and influence around. Both Arthur and Judd are different than normal college students, but Arthur knows how to play the game. Then, when they’re alone in each other’s company he’s able to dominate the other boy as they play out their sick fantasies.

In one moment, stirred by his accomplice Judd takes a girl to observe some birds — it happens to be near where a boy was killed — the bird calls in the distance play against the increasingly uncomfortable conversation. He plans to force himself on her, and though he tries he cannot bring himself to go through with it. There’s a sliver of decency still left inside of him.

Soon enough he and Artie are brought in for questioning by E.G. Marshall, a calm and collected beacon of authority. I’ve never seen The Defenders, but I could see him carrying it off with a level of pragmatic stability. Artie’s the one who walks in the room and tries to flip all the power dynamics. He pointedly stays standing as Marshall questions him sitting down. He’s confident enough not to be thrown off his game though he implicates them soon enough. They must vie for their lives in the courtroom.

Jonathan Wilk shows up sooner or later. Orson Welles hardly needs a great deal of time to put his mark on the picture. His haggard magnetism holds its own against anyone as he takes in this most harrowing case defending two privileged boys who were unquestionably implicated in murder.

The ensuing case comes with a myriad of perplexing caveats. Judd was coerced into trying to attack the girl, Ruth Evans. She later takes the stand in his defense. Martin Milner is an up-and-coming newshound who at one time was classmates with the boys and soon desires to watch them hang. His feelings toward Ruth are very protective.

Wilk is a bit of a moral cypher: He’s atheist who has the KKK showing up on his lawn blazing a cross as an act of intimidation. He also flips the case on its head with a rather unorthodox and risky decision.

He looks to appeal to the so-called Christian community of the court reminding them that cruelty breeds cruelty, and charity and love are what they have devoted their lives to. When he admits to a lifetime of doubt and questioning, it doesn’t necessarily mean he’s reached any final conclusions. It makes me appreciate him more for his moral transparency

Given the fact Welles was probably playing his version of Williams Jennings Bryant, a man who was also featured in Inherit The Wind portrayed by Spencer Tracy, it’s hard not to connect the two pictures. Their subject matter is very different and yet they both dwell on these ideas of religious beliefs and how narrow-minded societies can use them to stubbornly maintain their agendas. However, they can also be exploited.

For this reason, Compulsion is a fairly perplexing courtroom drama for the 1950s; between the performances of Stockwell and others it offers up something persistently interesting.

3.5/5 Stars