Recently I was appreciating some films starring Jeanne Crain, an alluring actress who was at the height of her popularity during the ’40s and ’50s. Although she was rarely touted as a preeminent actress, I wanted to highlight two films of hers that more than highlight her appeal.

Both Apartment for Peggy and Please Take Care of My Little Girl are set in the context of college in the post-war years. One has Craine as a newlywed wife tracking down student housing and in the latter film she plays a naive college freshman with sorority aspirations.

Read my thoughts on the two films below:

Apartment for Peggy (1948)

Apartment for Peggy is one of those Classic Hollywood films packed with pleasant surprises. The first of them is Edmund Gwenn. He’s best remembered as Kris Kringle in Miracle on 34th Street. Here he’s directed once more by George Seaton this time playing a listless university professor.

He lives off his pension in his crusty old abode spending his evenings with the same colleagues playing the same music they have for years. However, one evening he quite matter-of-factly announces his aspirations to commit suicide. He’s very rational about it. Still, his doctor won’t give him more than two sleeping pills at a time so he dutifully stores them up for a rainy day.

Then, something else far more momentous happens. He meets a young woman (Jeanne Crain) on a bench. Peggy Taylor motors about 1,000 miles per minute — her mind and conversations leapfrogging all over the place — so her new acquaintance can barely get a word in edgewise. He’s bowled over by her irrepressible zest for life. She’s precisely the person to prickle the professor’s curmudgeonly sensibilities. But she’s also the best equipped to turn Mr. Hypothetical’s life upside down for the better.

Because she tackles just about anything she sets her mind to with this same infectious verve. This is not just the age of the GI Bill (her husband is currently a student), but they are also dealing with a housing crisis. She puts her ear to the ground and manages to scrounge up a space in Pop’s decrepit attic. He’s quite against the imposition and still, Peggy keeps ping-ponging off the walls leaving no room for a rebuttal.

It’s one of many miracles how she spruces up the space and puts it through an astounding transformation. This is just the beginning. With Pop’s begrudging help, she conceives a daytime course for wives and mothers so they can learn about the great philosophers of the modern age (Spinozi included). They want to receive intellectual stimulation on par with their husbands so they can communicate with them.

Pops soon learns his new students are intrinsically driven to learn, and the professor is delighted to serve as their instructor because they seem to intuitively understand his teaching as his most receptive pupils. Their discussions are life-giving. You see already how Peggy single-handedly resurrects the old man so he’s able to see the world with new vim and vigor. Now it’s his turn to return the favor.

William Holden is just about the most innocuous thing about the picture, and that’s not to say he’s bad. Still, this is a picture made by the chemistry of Crain and Gwenn. It acknowledges the generation gap chafing between most any generations with varying perspectives on life with a comic touch. However, any conflict on the part of the elders ultimately engenders mutual affection.

Best of all, it’s a film about ideals and worthwhile pragmatism where the merits of both are made evident. But then again, film is not so much a science as it is a philosophy, an art — concerned with humanities — and the film works in this manner.

It gives off the appearance of a light, inoffensive comedy as we conceive would exist in post-war America. There are many. Certainly, this is true. However, it also sheens with warmth and goodness. Seeing the movie multiple times, the appeal of its brand of geniality just continues to bloom.

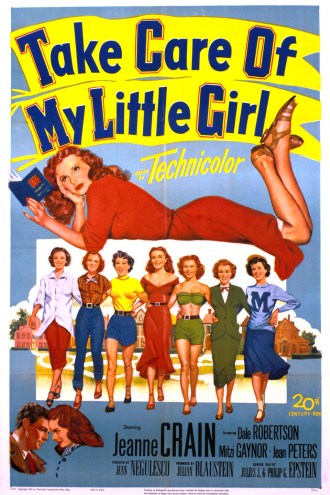

Take Care of My Little Girl (1951)

Sorority movies certainly feel like they’re solely made to meet an audience demand as a convenient cash grab. Take Care of My Little Girl wasn’t the first picture in this genre as I can think of at least a couple predecessors like Sorority House and These Glamour Girls (1939).

However, this movie actually had its origins in the master’s thesis of Peggy Goodin, who eventually turned her research into a novel. She was particularly concerned with how racial and religious discrimination played out in the highly moderated spaces of college sororities. To be clear, 20th Century Fox’s adaptation excises all of this commentary by casting their stable of homogenous Hollywood starlets (Jeanne Crain, Jean Peters, Mitzi Gaynor, Betty Lynn et al.) and a couple of male heartthrobs.

And yet that doesn’t mean the film doesn’t come with any teeth. For its day, it was actually rather controversial if only for its forthright portrayal of the social politics and hazing rituals that have continued to go under scrutiny generations later. The film looks different and yet at its core, it speaks to the very same issues we see today.

Jeanne Crain has such a radiant poise, it’s so easy to like her and not only like her but admire her for how she cares about others. Because she’s a shoo-in as a legacy at Tri-U sorority. Just as importantly, she’s probably the prettiest girl on campus. Not even the resident mean girl Dallas (Peters) can blackball her.

Liz cares deeply for her friends and isn’t totally swayed by the popularity contests even as she strives to make a good impression. She strikes up a rapport with a slightly cynical G.I.-turned-student (Dale Robertson), who helps advise her on classes and thrumbs his nose at the establishment after everything he’s been through. He recognizes something different in her that he likes.

Still, she’s not totally impregnable. Like any young person, she wants to be well-liked helping the class flirt (Jefferey Hunter) with the answers to his French exam. This in turn leads to being pinned. She’s the talk of the sorority house. And yet she’s not easy to categorize.

The picture is surprisingly poignant and perceptive. It’s not some hyperdramatic, superficial portrait of college life even if it’s playing to a specific audience. Also, thanks in part to Crain, there’s a genuine candor to the picture and a visible evolution to this young woman.

It may not be a lot, but it’s something. We do see her change as a human being. Surely college life looks so different now 70 years on from what we’re used to, and yet there are elements that have not changed. We still have fraternities and sororities and social hierarchies. I was aghast to realize even bluebooks have been around for well nigh a century!

This movie doesn’t necessarily suggest these institutions are inherently bad. However, sometimes we believe that tradition is good only because it’s the way things have always been done. But there should be better reasons. There need to be dissenters and people to challenge the status quo. There need to be brave folks who are willing to do what is right compared to what is easy. People who are loyal to their friends rather than simply playing the games for want of status and approval.

Even if the Epstein Brothers’ script forgoes some of the most intriguing aspects of the original story, I appreciate that they explore their topic with something a little bit more involved than superficial exploitation. It actually strives to be about something, however small.

3.5/5 Stars

Its title suggests that this film might be something like Lubitsch’s Heaven can Wait but The Devil and Miss Jones could easily hold the title as the original version of Undercover Boss. Although its main function is on the romantic and comic planes, it also has a bit of a social message behind it that signals for change.

Its title suggests that this film might be something like Lubitsch’s Heaven can Wait but The Devil and Miss Jones could easily hold the title as the original version of Undercover Boss. Although its main function is on the romantic and comic planes, it also has a bit of a social message behind it that signals for change. I despise you and I pity you. ~ Edmund Gwenn as Mr. Jordan

I despise you and I pity you. ~ Edmund Gwenn as Mr. Jordan Except at first what Harry does, does not seem like infidelity. In one integral scene Harry takes one of those bus tours to see the stars because, after all, Beverly Hills is that land of movie stars and their extravagant lifestyles. Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Oscar Levant, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jane Wyman are all given a nod. There are even a few playful in-jokes to the always genial Edmund Gwenn who turns up as the adoption agent. All of this is essentially fluff but it’s on that same ride where he meets someone — a woman named Phyllis Martin (Ida Lupino).

Except at first what Harry does, does not seem like infidelity. In one integral scene Harry takes one of those bus tours to see the stars because, after all, Beverly Hills is that land of movie stars and their extravagant lifestyles. Jimmy Stewart, Jack Benny, Oscar Levant, Barbara Stanwyck, and Jane Wyman are all given a nod. There are even a few playful in-jokes to the always genial Edmund Gwenn who turns up as the adoption agent. All of this is essentially fluff but it’s on that same ride where he meets someone — a woman named Phyllis Martin (Ida Lupino). It strikes me how it’s often the small, tiny, unassuming pictures that impact me the most and this film did wrench my heart over the course of only a very few minutes. The final court sequence sums up the reasons quite well because it ends the film on a moral note setting up a rather convicting paradigm.

It strikes me how it’s often the small, tiny, unassuming pictures that impact me the most and this film did wrench my heart over the course of only a very few minutes. The final court sequence sums up the reasons quite well because it ends the film on a moral note setting up a rather convicting paradigm. “Heathens are not always low just as Christians are not always high.” – Gregory Peck as Father Chilsum

“Heathens are not always low just as Christians are not always high.” – Gregory Peck as Father Chilsum