The production itself was fraught with some turbulence thanks to the contentious relationship between Miriam Hopkins and Edward G. Robinson. The latter actor was irritated how his costar was constantly trying to increase her part and keep him off balance with frequent dialogue changes. Regardless, the talent is too wonderful to resist outright.

How Howard Hawks ended up directing Barbary Coast is anyone’s guess, somehow getting involved as a favor to his screenwriting buddies Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur who spent numerous rewrites crafting something that the production codes might actually condone, overhauling the original novel’s plot points immensely.

Hawks has no major stake in the production and as such it hardly stands up with his most engaging works. Still, it does hold some merit demonstrating from the outset it’s a fast-moving, thick-on-atmosphere, period adventure set out in 49ers era California. That environment is enough to make a generally engaging yarn even if the narrative threads run fairly thin.

But the world is fully animated. Alive with honky-tonk pianos, crooked roulette wheels, and hazy city streets paved in mud. Just about what you envision gold country to be like, at least viewed through the inspired dream factory of old Hollywood. The blending of genre is a fine attribute as the picture is a mixture of historical drama, romance, comedy, adventure, and western themes sharing some relation to San Francisco (1936) and The Sea Wolf (1940), along with the lawless towns in Destry Rides Again (1939) or even The Far Country (1954).

A ship lands in the notorious San Francisco Bay, among its passengers a strangely out of place lady (Miriam Hopkins) and a gentlemanly journalist, Marcus Aurelius Cobb (Frank Craven). They are met with quite the reception committee of local undesirables.

Walter Brennan is a standout as the scrounging, toothless, eyepatch-wearing Old Atrocity preying on unsuspecting outsiders who happen to make their way to the streets of San Fransisco. Mary Rutledge is in town to join her fiancee who messaged her to come out and meet him as he’s struck it rich. She promptly finds out her man is dead, no doubt knocked off by the crooked Louis Chamalis (Edward G. Robinson).

With his restaurant the Bella Donna and adjoining gambling house, the ruthless businessman rakes in the profits by robbing prospectors of their hard-earned caches and getting tough when they object to his dirty practices.

Miriam Hopkins, both radiant and sharp, isn’t about to snivel about her lost prospects and heads straight away to the Bella Donna to see what business she can dig up for herself. There’s little question she causes quite the stir because everyone is taken with this newly arrived white woman — including Louis. As Robinson’s character puts it, she has a pretty way of holding her head, high falutin but smart. That’s her in a nutshell as she earns the moniker “Swan” and becomes the queenly attraction of the roulette wheels.

It’s there, an ornery and sloshed Irishman (Donald Meek in an uncharacteristic blustering role) gets robbed blind and causes a big stink. Louis snaps his figures and his ever-present saloon heavy Knuckles (Brian Donlevy) makes sure things settle down.

He’s sent off to do other jobs as well. In one such case, he shoots someone in the back but with a mere Chinaman as an eyewitness in a kangaroo court presided over by a drunk judge, there is little to no chance for legitimate justice. Then there’s the manhandling of free speech by forcibly intimating Mr. Cobb in his journalistic endeavors and nearly demolishing his printing press for publishing defamatory remarks about the local despot. Swan is able to intercede on his behalf as Cobb resigns himself to print droll rubbish and it seems Louis has won out yet again.

Joel McCrea has what feels like minuscule screentime and achieves third billing with a role casting him as the romantic alternative, a good guy and yakety prospector from back east who is as much of an outsider as Ms. Rutledge. He’s eloquent and strangely philosophical for such a grungy place. He’s also surprisingly congenial. It catches just about everyone off guard. First, striking up a serendipitous friendship with the woman and gaining some amount of rapport with Chamalis for his way of conversing.

Though the picture stalls in the latter half and loses a clear focus, the performances are nonetheless gratifying as Robinson begins to get undermined. Vigilantes finally get organized using the press to disseminate the word about Louis and simultaneously battle his own monopoly with an assault of their own.

One man must die for the right of freedom of speech to be exercised while another man is strung up like an animal. Our two lovebirds get over the lies they told each other looking to flee the ever-extending reach of a jealous lover. Chamalis is not about to let them see happiness together. The question remains if they can be rescued in time from his tyrannical clutches. The dramatic beats may well be familiar but Barbara Coast still manages to be diverting entertainment for the accommodating viewer.

3.5/5 Stars

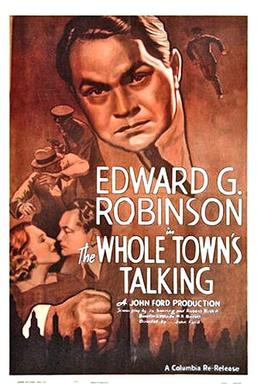

Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum.

Comic mayhem was always supercharged in the films of the 1930s because the buzz is palpable, the actors are always endowed with certain oddities, and the corkscrew plotlines run rampant with absurdities of their own. Penned by a pair of titans in Jo Swerling and Robert Riskin, The Whole Town’s Talking opens with an inciting incident that’s a true comedic conundrum.

e Falcon was the first great film-noir then this film has to be a refining and improvement of the genre.

e Falcon was the first great film-noir then this film has to be a refining and improvement of the genre.