“The love of a man for a woman waxes and wanes like the moon…but the love of brother for brother is steadfast as the stars, and endures like the word of the prophet.” ~ Arabian Proverb

No matter what Joseph Von Sternberg thought of such a proclamation, we can concede his Morrocco was a film concerned with the former. Von Sternberg’s dalliances with Marlene Dietrich behind the scenes and then Dietrich and Cooper in front of the camera are a living testament.

Beau Geste stakes its claim early to being a film of undying brotherly love. It brings to mind the words of scholar and author C.S. Lewis when talking about philia as a “side by side, shoulder to shoulder” appreciative love. It comes not by looking at each other but having a vision of something in front of us.

“Every step of the common journey tests his metal; and the tests are tests we fully understand because we are undergoing them ourselves. Hence, as rings true time after time, our reliance, our respect and our admiration blossom into an Appreciative love of a singularly robust and well-informed kind.”

I think this is a perfect illustration to begin to understand why Beau Geste is an initially compelling hero’s journey because it relies on a joint adventure to bring out expressions of deep-rooted love.

Admittedly, William A Wellman’s film is a close remake of the 1926 silent Ronald Colman vehicle. One element this film borrows from its predecessor are intertitles, and they’re too many of them for a talking picture.

But soon enough a cold open places us within the ranks of some French Legionnaires who come upon a fortress only to find the stronghold littered with the bodies of their comrades propped up against the walls. Something dreadful must have happened to them. For now, we get no more explanation as the story quickly fades back into the past, 15 years prior.

There we meet five children, three of them named Geste, one of them named Isobel, and the fifth a bespectacled killjoy named Augustus. You see, the others are still enraptured with adolescent imaginations that find them gallivanting around on the most glorious adventures as soldiers or possibly members of King Arthur’s court.

Their exploits are to be remembered with a Viking’s funeral with a dog lying at their feet. The beauty of their temperaments is the fact they hold on to a bit of their youthful exuberance when they grow into young men.

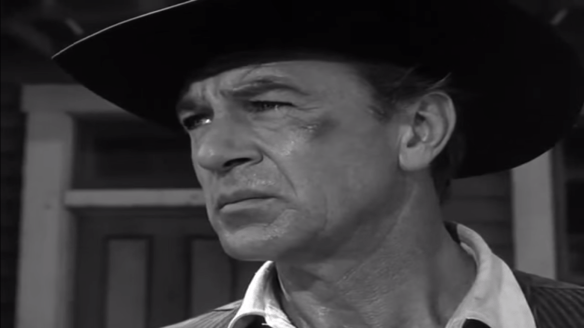

It always is a bit of a start when you jump from child actors to their corresponding adult selves. In the picture, I couldn’t quite make the jump seamlessly but no matter. All I know is I do have an appreciation for our leads — that is the three Geste brothers. They really are rather like the three Musketeers with Gary Cooper, Ray Milland, and Robert Preston making a jocund company.

Also, on a side note, this is too perturbing for me not to mention. I double-checked records multiple times and our three stars were born in 1901, 1907, and 1918 respectively. I’m still trying to figure out why Robert Preston hardly looks any younger than his costars or at least Milland. Maybe it’s his mustache. At any rate, age differences aside, the chemistry is present.

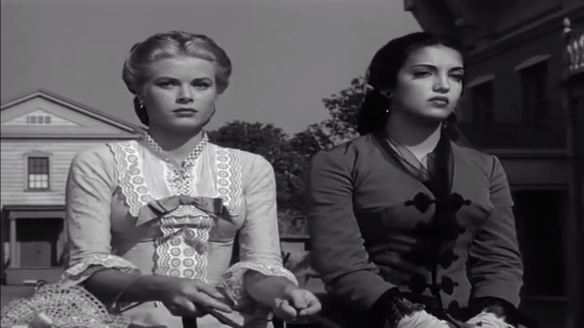

What is not present is the priceless jewel “The Blue Water” that was stolen one evening from the home of their adopted aunt Lady Patricia. The same evening Beau runs off to the Foreign Legion followed soon thereafter by Digby (Preston) and finally John (Milland) who gives one parting embrace to Isobel (Susan Hayward) before leaving on the grand adventure. Hayward is exquisitely beautiful and though her ingenue role is in no way groundbreaking, we have the solace of many meaty performances to come.

The film’s true standout is Brian Donlevy as an unscrupulous tyrant in charge of new recruits. He eventually finds himself commanding the entire outpost with the whole outfit threatening insubordination. His hunger for power verges on the deranged.

My expectations were more of the rip-roaring adventure variety but as the previous commander’s remarks on his deathbed, “Soldiers die as much from fevers as they do battles.” Meanwhile, Digby is unceremoniously pulled away from his brothers on a work detail and subsequently, misses out on most of the final act.

I would say wholeheartedly the film is salvaged in its last push as we are granted the spectacle we have been waiting for as the remaining men hold down the fort against incoming marauders. It makes one nearly cry out “Remember The Alamo!” The sentiment is there anyway.

It seems a horrible thing to say, but Cooper affected me more when he was on the verge of death than when he was alive. The all but wordless finale plays particularly cryptically as Digby sneaks around the compound to carry out his oldest brother’s wishes.

I must admit to dismissing Beau Geste‘s storytelling prematurely as it evoked greater complexities than I would have expected. The mechanisms of the opening and overlapping moments are more intricate than I might have given them credit for. The mysterious words spoken once upon a time, while Beau was hiding in the suit of armor, come to fruition as do the opening moments, neatly folding back into the tale.

The reunion of John with Isobel and his Aunt arrives in the nick of time to satiate audience wish-fulfillment. It almost elevates the film wholeheartedly, but the pacing and where the story chooses to focus its efforts feel scattered. Had they come together more succinctly we might be hailing Beau Geste one of the great actioners.

While Gary Cooper in a foreign legion kepi is nonetheless iconic, I am apt to remember him more so for Morocco (even if that picture belonged to Dietrich). Although if one is sentimental enough to forgive the faults, it’s painless enough to say Beau Geste belongs to three devoted brothers. Coop, Milland, and Preston maintain a spirited solidarity throughout.

3.5/5 Stars

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to.

The proverbial stranger rides into town looking for a place to wash up and grab a bite to eat. We get the sense he might be sticking around. Except, soon enough, he turns right back around and buys a ticket on the first train out of town. Because he has business to attend to. Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show.

Though the image quality of the print I saw hardly stands the test of time, there’s something almost modern about The Virginian’s characterizations or at least what it deems interesting to show. Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination.

Again, I must confess that I have not read yet another revered American Classic. I have not read A Farewell to Arms…But from the admittedly minor things I know about Hemingway’s prose and general tone, this film adaptation is certainly not a perfectly faithful translation of its source material. Not by any stretch of the imagination. “He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett

“He could never fit in with our distorted viewpoint, because he’s honest, and sincere, and good. If that man’s crazy, Your Honor, the rest of us belong in straitjackets!” ~ Jean Arthur as Babe Bennett Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.

Before the exoticism of Casablanca, Algiers, or even Road to Morroco, there was Josef Von Sternberg’s just plain Morocco but it’s hardly a run-of-the-mill romance. Far from it.