Leave No Trace instantly reminded me of two distinct reference points. The first relates to a man named Richard Proenneke who lived in the Alaskan wilderness for 30 years building his own cabin and raising his own food in a life of tranquil solitude.

Leave No Trace instantly reminded me of two distinct reference points. The first relates to a man named Richard Proenneke who lived in the Alaskan wilderness for 30 years building his own cabin and raising his own food in a life of tranquil solitude.

Then, the other comes from a book I read when I was a kid called My Side of a Mountain, written by Jean Craighead George, following a young man who literally goes out into a forest, builds himself a home hewn out of a tree, and subsists off the land. The common themes running through these narratives are already quite obvious.

If you’re like me, especially in this technology-saturated world of ours, sometimes it seems like we’re pretty helpless and ever plugged into our devices. But some of us look at such stories and see a sense of romanticism. It seems like a nice idea — like a picnic or going camping — out communing with nature. Except it only goes so far. We love to read about it and live vicariously through others but we stop short of getting involved ourselves.

The pair existing in Leave No Trace is actually up to the challenge of living this life on the move, out in an Oregon nature reserve, surviving off the land, and in so many ways remaining self-sufficient. They are far closer than many of us can probably ever comprehend. Because everything they do has near life and death consequences. You don’t live as they do without getting close and forming a bond. There is no other way to exist aside from constant symbiosis.

The father, Will (Ben Foster), a former member of the military, has passed down so many practical skills to his daughter, training her up to survive out in the wild. It’s like an extreme version of homeschooling. Tom’s (Thomasin Mackenzie) social skills are lacking but if you stacked her up against anyone her age she’s probably more resourceful and capable than any of them. Because her brain has not been programmed by technology nor is it awash in a world of a vacuous glut of constant stimuli. Their total immersion in nature is refreshing as is their independence and very stripped down lifestyle.

But this journey is particularly worthwhile because it is still set in our world and so these two very unique individuals are forced to brush up against society and the norms in place. Technically, they are trespassing and so in a way they take on the mantle of fugitives constantly on the run as nomads dodging the authorities. You can only hide and break camp and get away so long. Even for people as attuned and regimented as them, there’s always a slip-up.

Now there are good folks in the world — social workers and then common, ordinary people who try and give them a leg up. There are ways to get Tom and her dad back into society without completing severing their ties with the naturalism that is most comfortable for them.

It is a story about a relationship, a very close-knit relationship between a father and daughter. But it becomes a story of maturation as well. Tom realizes her dad is hardwired a certain way. Whether it is restless feet, the demons of post-traumatic stress, or some unnamed specter, he’s constantly dodging, or simply discontent with modern society. He is never capable of settling down.

Meanwhile, she is willing to make allowances and sculpts each place they find together into a new home. Still, it never feels like she’s selling out completely. True, she’s enamored with a new bicycle and mentions in passing how having a phone would make it easier to communicate and yet the core aspects of her character do not waver. Tom still maintains her immense inquisitiveness and affection for all flora and fauna in the great outdoors. She loves dogs, makes friends over rabbits and honeybees. These are the places she is truly in her element.

However, she is also a willing participant, ready to enmesh herself in an ecosystem of people. She gets comfortable around the relationships she makes and yearns to set roots down somewhere. The great revelation comes when she realizes her father can never be that. Instead of always following his lead, she becomes more and more of her own person, making her own decisions. It has nothing to do with a split or not loving him anymore. This is about being mature enough to let other people go and being okay with the realization.

Read only as words on the page, Leave No Trace could be chock full of high drama but it wins its victories through the subtility of its leads and the more nuanced touches to fill in around the naturalism and bevy of sojourning survival tactics. Debra Granik directs the movie with an eye attuned to relationships and while generally unadorned, the movie is full of wonderment in the world’s natural beauty.

It exhibits the lush greenery quintessential to the rainy, fresh imagery that the Oregon coast conjures up. There is arguably no better film that I’ve seen to capture this environ in all its verdant glory. While a completely different sort of film, I could not but for a moment recall one of the greenest films to ever be on the silver screen, The Quiet Man. Because whether romantic or familial there’s no question the milieu of a film is so crucial in fashioning how we perceive a cinematic experience. Like its predecessor, Leave No Trace is a roaring success channeled through tranquil trails of its own creation. Sometimes those trails must break off and lead toward different destinations. Being content in moving on is key.

4/5 Stars

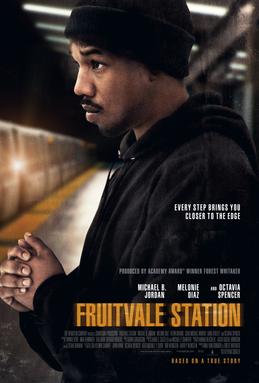

Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition.

Ryan Coogler is from Oakland, California. He was attending USC Film School in 2009 when Oscar Grant III was shot near the BART station. From those experiences were born his first project. He envisioned Michael B. Jordan in the lead role. Thankfully his vision and the casting came to fruition. Get Out seems like a simple enough premise. Ridiculously simple even. We’ve seen it millions of times in rom-coms or other fare. It’s the fateful day when the significant other is being taken to meet the parents. Whether they pass this test will have irreversible repercussions on the entire probability of the relationship’s success. Maybe that’s a tad over the top but anyways you get the idea as Rose (Allison Williams) drives her boyfriend Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) to meet her parents.

Get Out seems like a simple enough premise. Ridiculously simple even. We’ve seen it millions of times in rom-coms or other fare. It’s the fateful day when the significant other is being taken to meet the parents. Whether they pass this test will have irreversible repercussions on the entire probability of the relationship’s success. Maybe that’s a tad over the top but anyways you get the idea as Rose (Allison Williams) drives her boyfriend Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) to meet her parents. I wrote an

I wrote an  In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing.

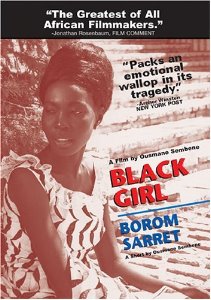

In Manchester by the Sea, you can distinctly see Kenneth Lonergan once more translating some of his skills as a playwright and stage director into his film. There’s a very inherent understanding of two-dimensional space and how images can be framed in a very linear way as they would be seen by an audience taking in a stage production. But even more noteworthy than that is his dialogue which functions in remarkably realistic ways. Some will easily write this film off as the sheer doldrums because it’s fairly fearless in its pacing. What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once.

What’s fascinating about this film is how it manages to give voice to those who are normally silenced and even in her subservience this narrative powerfully lends agency to a young Senegalese woman’s perspective. Because even when she is silent and words are not coming out of her mouth and her status ultimately makes her powerless, the very fact that her mind is constantly thinking, her eyes observing and so on mean something. Inherently there’s a great empowerment found there even if it’s only known by her and seen by the outside observer peering into her life. That’s part of her. We are given a view into what she sees. We can begin to understand her helplessness and isolation. Where she came from and the life she left behind. Giving up the master narrative of the entitled and shown the flip side of the world for once. There’s a moment in Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen where Nadine (Hailee Steinfeld) suffers the ultimate humiliation third wheeling with her older brother Darian (Blake Jenner) and her (former) best friend Krista (Haley Lu Richardson). Needless to say, the evening is less than stellar but it gets worse after Nadine feels like she’s been totally betrayed. She’s been hating her brother recently and her best friend is dead to her now. The fact that she sets up an ultimatum doesn’t make things any better.

There’s a moment in Kelly Fremon Craig’s The Edge of Seventeen where Nadine (Hailee Steinfeld) suffers the ultimate humiliation third wheeling with her older brother Darian (Blake Jenner) and her (former) best friend Krista (Haley Lu Richardson). Needless to say, the evening is less than stellar but it gets worse after Nadine feels like she’s been totally betrayed. She’s been hating her brother recently and her best friend is dead to her now. The fact that she sets up an ultimatum doesn’t make things any better.