The film opens with newsreel footage delivered to us in an undoctored format effectively presenting us a view into the past. It is the momentous (some would say fateful) day Adolf Hitler made his triumphant visit to see Benito Mussolini in Italy.

The film opens with newsreel footage delivered to us in an undoctored format effectively presenting us a view into the past. It is the momentous (some would say fateful) day Adolf Hitler made his triumphant visit to see Benito Mussolini in Italy.

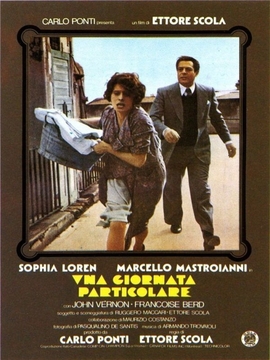

The year is 1938. And it has all the pomp, circumstance, military exhibitions, and blind nationalism one comes to expect with such historical depictions. Director-screenwriter Ettore Scola elects to give us the past instead of totally constructing a version of it. Because that is not what his film is about.

Even to consider Fellini’s farcical take on fascism in Amarcord, complete with swooning beauties and talking Mussolini faces in flowers, A Special Day couldn’t be more divergent. It works and operates in a much smaller more confined space, serving its purposes just fine. As the movie itself opens, we are immediately met with the most confounding of palettes — an ugly clay-colored hue — hardly the best for drawing on fond memories. In fact, it’s utterly unappealing.

This is not a criticism, mind you, because the pervading drabness is another calculated creative decision. What it provides is a very concrete articulation of the world. Furthermore, without committing to the broader context, Scola is able to focus his attentions on one building.

So yes, there is this huge cultural event with a gravitational pull dragging everyone out of the house in droves to celebrate with patriotic fervor. Everyone wants to see the Fuhrer and Il Duce for themselves. But this is all pretense, again, serving the smaller, more intimate scale of the film. It’s for the best.

Not totally unlike Hitchcock’s Rear Window, the housing complex becomes a limiting factor, but also a creative asset. The architecture and space evolve into something worth examining in itself. Within its confines, our two protagonists are thrown together thanks to an escaped myna bird. One is a long-suffering housewife (Sophia Loren) forced to stay at home while her family enjoys the festivities. She’s a middle-aged Cinderella with all the youthful beauty sucked out of her.

Her husband (an oddly cast and dubbed John Vernon) is an arrogant party supporter and all her six children are either brats or too young to know any better. Her station as a mother and wife feels totally underappreciated, even dismissed.

The other forgotten person she happens to meet is a radio broadcaster (Marcello Mastroianni), unwittingly diverting him from an attempt at suicide. Because the current regime has no place for subversive naysayers like him on the national airwaves.

There’s a questioning of whether or not there’s enough for a film to develop. Can it hold on and keep us on board for over an hour? Given everything so far, it’s a no-frills scenario. There’s not much to work with, and success in itself seems like a tall order. Thank goodness we have the likes of Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni. The promise of having them together is a worthy proposition and in this case, it hardly disappoints.

If you’ve only seen them in their star-studded, glamorized roles, prepare to be astounded. Loren could never look completely dowdy, but there’s definitely something forlorn about her. She carries it off quite well. Likewise, Marcello, normally a suave fellow, still has his prevailing moments of charm, but he too is equally subtle.

At least in the case of Loren, it seems like Hollywood only ever saw her as a screen goddess with an accent, and thus cast her in roles catering to that predetermined persona. And yet in her native Italy, in a movie like Two Women (1961) or here in A Special Day, it’s as if they gave her the freedom and the trust to stretch herself and really prove who she was as a bona fide actress.

The little doses of magic they drum up together carry scenes and if you’ve ever seen any of their movies, the intuitive chemistry coursing between them is, by now, almost second nature. Dancing steps of the rhumba to the cutouts on the floor. For one single moment, a saucy tune drowns out the choruses of a fascist regime.

Later she tries to quickly style her hair in the bathroom as he bungles grinding the coffee and sweeps it under the rug like a sheepish schoolboy. Or he makes his valiant attempt at fixing the lamp over the kitchen table that always leaves Antonietta bumping her head. These are the lighter notes.

But if these are the distinct instances of near frivolity, then A Special Day is about so much more on a broader scale. It casts an eye on a society that deems women as totally auxiliary in both intelligence and importance.

Likewise, one is reminded about the institutionalized hatred including vitriolic prejudice against homosexuals. Where people have lost their image and are merely cogs in a political, faux-religion of the state. Not everyone fits in. Gabriele even exhibits a touch of mild insurrection to the state by not abstaining from using the banned “lei” instead of “voi” when addressing others, as the former was seen as too effeminate by Italy’s fearless leader.

If not totally radical, the relationship at the core of this movie feels countercultural, even as it probably taps into the basic longings of many. In some strange, miraculous way they understand one another, unlike anyone they ever have before.

It’s how the film is able to be an empathetic portrait of humanity. Never has it been more evident that understanding can exist anywhere and between anyone in the most unusual of circumstances. So by the time the day’s festivities are winding down and the crowds rumble back in, the two kindred souls part ways to their separate ends of the courtyard, and yet there’s no way not to think about one another.

Gabriele starts packing up to be shipped off and deported because Mussolini’s regime is no place for a man like him. Antonietta puts together dinner for her family — all the normal duties required of her — existing once more as the silent life force behind the entire household. Her mind can’t help but wander to the only person who seems to know her, just as one’s eyes can help but glance at the light he helped fix only hours before.

He takes one final survey of his apartment, his room goes dark, and he’s escorted out of the courtyard, quietly, without any fanfare. The wide void between their apartments has never felt greater. It is the antithesis of a Rear Window ending.

After a few moments of leafing through The Three Musketeers — the book he gifted her — she wanders off to bed and follows suit by turning out the light. Darkness overtaking the day in the never-ending rhythms of life.

If it wasn’t apparent already “a special day” is meant to elicit two connotations. The state would have you believe the sights of Hitler, Mussolini, and grand feats of military might are the type of memories you won’t soon forget. Perhaps they’re even worthy of telling your children about someday.

However, for others, “a special day” means something far more. It has to do with empathy and truly knowing someone and being known like you’ve never been known before. For isolated people in a callous and lonely world of monotone, it’s so much more than all the bells and whistles at a parade. In its own unassuming way, A Special Day is a heart-wrenching love story to the nth degree.

4/5 Stars

Ever since the days of his

Ever since the days of his

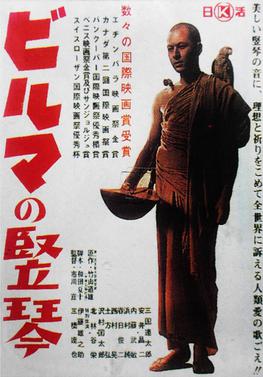

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.

Put in juxtaposition with Kon Ichikawa’s later rumination on WWII, The Burmese Harp is a romanticized even simplistic account of the Japanese perspective of the war. However, this is not to discount the mesmerizing nature of the story that is woven nor the overarching truth that seems to linger over its frames.