“Times had changed. It was the age of James Bond and Vietnam.”

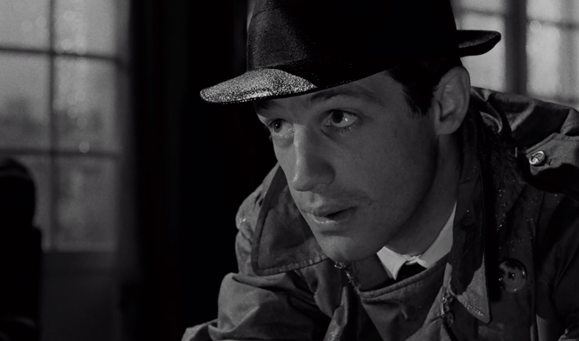

The film opens with a casual conversation between two young people: the young man, Paul (Jean-Pierre Leaud), bugs the girl, Madeleine (Chantal Goya), sitting across the way. Then, this conversation between young people in a cafe gets rudely interrupted by a marital spat that ends in a gunshot. Surely these are Godard’s proclivities at work.

One could say form follows function. Masculin Feminin is another reminder of how literary his cinema is. We often think of his films for their visual aesthetic thanks to the likes of Raoul Coutard (or Willy Kurant here). There’s no denying this, but they are always so pregnant with ideas and thoughts, some fully formed others feel like they were scribbled out on a notepad (because they were). It’s a task to be inundated with it all as he willfully challenges any level of perspicuity.

However, whether you venerate or loathe Godard, his cinema is a tapestry woven together from all his influences. It feels like dialectical cinema where everything is a symposium of love, arts, and politics as young people converse with explosive intertitles blasting away between scenes. But that doesn’t mean everything is a logical progression. Godard gives himself license to follow every passing whim.

Other times it’s uncomfortably direct. Leaud as his avatar starts interrogating Madeleine as she powders her face, but he gets away with it, since he’s always idealistic and a bit of a romantic. He asks her, “What’s the center of the world?” When pressed, he thinks it’s “Love” and she would have said “Me.”

Eventually, he spends more time with her and gets to know her roommates too, and he finds a new job polling the public. Leaud “polls” Ms. 19 giving her a line of probing, deeply personal questions. Later, he has a whole conversation about mashed potatoes and a father discovering how the earth orbits around the sun.

Godard is always in conversation with the films that inform him, but with Masculin Feminin we see a much broader acknowledgment and exploration of the contemporary culture. Madeleine’s meteoric rise as a Ye-Ye singer finds her on the charts in Japan only surpassed by The Beatles, Frances Gall, and Bob Dylan. Not bad!

That’s also not to say Godard gives up being in dialogue with films as well, including his own, which had become part of the cultural conversation in their own right. Bridgitte Bardot (from Contempt) shows up receiving notes from her director. Madeleine playfully chastises her beau, “You’re not Pierro Le Fou. He stole cars for his woman!”

Later, they sit in a darkened theater together watching a perturbing arthouse movie:

“We went to the movies often. The screen would light up, and we’d feel a thrill. But Madeline and I were usually disappointed. But Madeline and I were usually disappointed. The images were dated and jumpy. Marilyn Monroe had aged badly. We felt sad. It wasn’t the movie of our dreams. It wasn’t the total film we carried inside ourselves. That film we would have liked to make, or more secretly, no doubt, the film we wanted to live.”

If this doesn’t sum up the aspirations of the youth in front of the camera staring up at the screen within the screen, it must hold true for the young batch of filmmakers who Godard himself came up with. It’s a perplexing bit of dialogue and one of the most apparently self-reflexive and personal annotations within the entire picture.

As is, all of Godard’s male heroes and stand-ins feel dense although Leaud is always miraculously able to pull off some boyish prank or a bit of mischief and still maintain some semblance of relatable humanity.

Otherwise, how could girls ever put up with these guys much less love them? All the young women are pestered to no end and rendered endearing for all they must endure. I think of Ms. 19 and Elisabeth (Marlene Joubert) in particular. We pity them.

What do we do with the totality of this picture? From experience, you usually run into issues when you try and find the narrative arc or a conventional form to follow. Because Godard’s films boast so much in ideas, asides, and digressions. There’s so much to be parsed through and digested.

It’s easier to follow impressions, a train of thought here, or a standalone scene there that left some sort of tangible impact. In the social tumult and the moral morass of the 1960s, it’s almost as if within the collage of the film, we’ll find some substantive meaning. Then, again maybe not.

Leaud walks down the street with a girl and pops into a cafe for a moment only to come back out. He continues to walk and says, “Kill a man and you’re a murderer. Kill thousands and you’re a conqueror. Kill everyone and you’re a God.”

She responds, “I don’t believe in God.” Frankly, I don’t blame her, and if that’s the world’s conception of who God is, I wouldn’t want that God either. Still, we all try and answer existential questions with something, be it politics, pop songs, or fleeting teenage romance.

I read Godard’s film was restricted to adult viewers, but he probably thought he was doing a public service announcement for the youth generations in his own individual attempt to put a voice to the times. Whatever your thoughts on Godard or Coca Cola and Marx, alongside British Swinging London time capsules, Masculin Feminin helps capture this particular moment of ’60s European culture in a bottle.

It feels increasingly difficult to reconcile all the warring forces fighting for primacy and as a young person just trying to find love and make sense of one’s life, it’s never easy. We have more questions than answers. However imperfectly, Masculin Feminin synthesizes some aspects of this universal phenomenon, one that’s not totally restricted by time. We can all relate to this idea as long as we were young once.

4/5 Stars

Note: This review was written before the passing of Jean-Luc Godard on September 13, 2022.

The Wild Child (L’Enfant Sauvage in French) is based on “authentic events,” as it says because Francois Truffaut became fascinated by a historical case from the 1700s. A feral boy was discovered out in the forests and then taken under the tutelage of a benevolent doctor.

The Wild Child (L’Enfant Sauvage in French) is based on “authentic events,” as it says because Francois Truffaut became fascinated by a historical case from the 1700s. A feral boy was discovered out in the forests and then taken under the tutelage of a benevolent doctor.

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette

“You can’t just do anything at all and then say ‘forgive me!’ You haven’t changed a bit.” ~ Colette Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively.

Antoine Doinel is a character who thinks only in the cinematic and it is true that he often functions in a bit of a faux-reality. He seems normal but never quite is. He seems charismatic but we are never won over by him completely. Still, we watch the unfoldings of his story rather attentively. One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.”

One of Jean-Luc Godard’s strengths is his capability of feigning pretentiousness, while still simultaneously articulating humor. His film opens with its first of many inter-titles, “A film adrift in the cosmos,” followed by the equally poignant “A film found in a dump.” Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity.

Conflagrations engulf cars and human bodies while above the din comes the piercing screams of a woman bemoaning the loss of her Hermes handbag. We cannot take this anyway but humorous because it once again is yet another moment of utter insanity. But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns.

But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns. Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum.

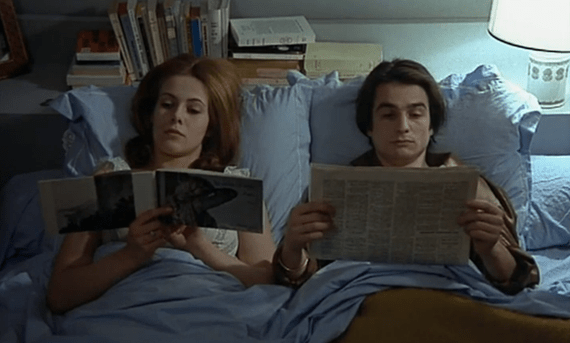

Charles Trenet’s airy melody “I Wish You Love” is our romantic introduction into this comedy-drama. However, amid the constant humorous touches of Truffaut’s film, he makes light of youthful visions of romance, while simultaneously reveling in them. Because there is something about being young that is truly extraordinary. The continued saga of Truffaut’s Antoine Doinel is a perfect place to examine this beautiful conundrum. In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on.

In fact, all in all, if we look at Doinel he doesn’t seem like much. He’s out of the army, obsessed with sex, can’t do anything, and really is a jerk sometimes. Still, he manages to maintain an amicable relationship with the parents of the innocent, wide-eyed beauty Christine (Claude Jade in her spectacular debut). Theirs is an interesting relationship full of turbulence. We don’t know the whole story, but they’ve had a past, and it’s ambiguous whether or not they really are a couple. They’re in the “friend zone” most of the film and really never spend any significant scenes together. Doinel is either busy tailing some arbitrary individual or fleeing pell-mell from the bosses wife who he has a crush on. By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.

By the time he’s given up the shoe trade and taken up tv repair he’s already visited another hooker, but Christine isn’t done with him yet. She sets up the perfect meet-cute and the two young lovers finally have the type of connection that we have been expecting. When we look at them in this light, sitting at breakfast, or on a bench, or walking in the park they really do seem made for each other. Their height perfectly suited. Her face glowing with joy, his innately serious. Their steps in pleasant cadence with each other. The hesitant gazes of puppy love.