I was thinking about how although Joaquin Phoenix has steadily become one of the most admired actors at work in film today, I don’t necessarily enjoy him or closer still I’ve never felt a kinship for him when he’s onscreen. Ethan Hawke, Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver, even Leonardo DiCaprio have offered performances where I sense their humanity and empathize with them.

I was thinking about how although Joaquin Phoenix has steadily become one of the most admired actors at work in film today, I don’t necessarily enjoy him or closer still I’ve never felt a kinship for him when he’s onscreen. Ethan Hawke, Andrew Garfield, Adam Driver, even Leonardo DiCaprio have offered performances where I sense their humanity and empathize with them.

I forget Phoenix’s capable of the kind of mundane naturalism that also defines a certain mode of acting. C’mon, C’mon is a reminder he can be a rudimentary person, a normal human being, and when he’s playing Joker or Napoleon, it’s not better just different (Why does everyone have to be eccentric? It’s okay to be normal too).

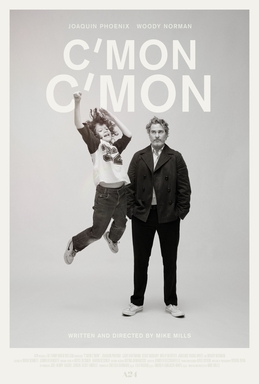

Mike Mills’ stylized black and white movie follows a radio journalist named Johnny (Phoenix) who is enlisted by his sister (Gaby Hoffman) to watch over her 9-year-old son Jesse (Woody Norman) as she attends to a family emergency. He’s an unattached working professional who’s hardly equipped to be a caregiver, but who is?

It’s a learning experience for both uncle and nephew as they get used to each other in Los Angeles. The movie takes them all across the country as Johnny conducts interview with youth across the country. Jesse becomes his boom man learning what it is to do sound.

Those of a certain generation will know about Art Linkletter and “Kids Say the Darndest Things.” Johnny and his team seem to give us an update on this; sometimes adolescents have a wisdom we would all do well to tap into for simple, clear-sighted lucidity about the future. From time to time, sans the coarser language from the adults, it’s a Mr. Rogers movie. There’s a mild sense of wonderment and an appreciation of what the younger generations can teach us.

They have ways of asking the most searching and honest questions. Jesse questions why his mom is away. Johnny explains she had to check in on his father (he’s a composer going through a nervous breakdown). Why does his dad need help? It’s not an easy answer that’s cut and dry. And suddenly you appreciate the tightrope walk it is to be a parent and also the unprepossessing honesty kids maintain.

Adults are fractured and imperfect often hurting the ones we love. Divorce, the problem of evil, why bad things happen to good people, adults struggle with these issues for most of their lives. Kids are not immune to any of this and are affected by it all.

C’mon C’mon is not so much a road movie as it is about impressions and impressions in particular about familial relationships. Brother and sister hold a two-way conversation for most of the picture from different states keeping a dialogue going. It provides a very loose framework.

With The Velvet Underground acting as an auditory transition the story shifts to New York. It’s more Noah Baumbach than Woody Allen but the West Coast, East Coast juxtaposition is real, and it plays well in the movies. Meanwhile, New Orleans offers up its own unprecedented aesthetic to the patchwork.

Otherwise, the film takes an observational approach as uncle and nephew experience life together. It’s not a raw-raw, grab-life-by-the-horns pump-up piece; it’s smaller, from the ground up about moments and the kind of trifles you catch if you stop long enough to appreciate them.

I’m still trying to decipher if there is enough here for a conventional movie, but of course, I answered my own question because this is not a movie you get every day. It just needs to find the right audience and Mike Mills no doubt has a tribe of followers ready and waiting.

In a particular interview, a young man is asked what happens to us when we die. He offers up that he and his mother are Baptist so he believes in heaven. Pressed further he says he imagines it as a meadow with one big tree where you lay on the grass with the flowers and stare up at the sun relaxing; it wouldn’t be too hot.

The interviewer marvels that it sounds beautiful. Yes, it does. There’s no agenda or politics or vanity. The response feels so genuine. Does anyone remember what Keanu Reeves said in response to the question of what happens when we die? After a pause, he answered, The people who love us will miss us very much…I feel like we’re all searching for those shards of wisdom.

One of my favorite bands actually has a deep cut that’s called “C’mon, C’mon” and the lyrics go like this:

So c’mon, c’mon, c’monLets not be our parentsOh, c’mon, c’mon, c’monLets follow this throughOh, c’mon, c’mon, c’monEverything’s waitingWe will rise with the wings of the dawnWhen everything’s new

These words don’t speak to Mike Mills’ movie precisely, but in an impressionistic way, I can tie them together in my mind. There’s something generational about it — this youthful sense of wonder and optimism — and the desire to spur others on.

When I hear the phrase C’mon, C’mon, there’s a playfulness welcoming someone else in, whether it be into a kind of life or an uncertain future, even a game of tag or a bit of make-believe. C’mon, C’mon is an open hand. I want this kind of posture.

Because there is a not-so-subtle difference between childish and childlike. I want the latter for my life. Actors, directors, writers, creatives, I feel like they never quite lose this spirit at their very best, and it’s something worth fighting to hold onto. Sometimes our youngest members can give us so much if we have the humility to learn from their example.

3.5/5 Stars

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes.

It’s not something you think about often but stoners and film noir fit together fairly well. Why more people haven’t capitalized on this niche is rather surprising. Think about it for a moment. Film noir in the classic sense is known for its private eyes, femme fatales, chiaroscuro cinematography, and perhaps most importantly a jaded worldview straight out of Ecclesiastes.