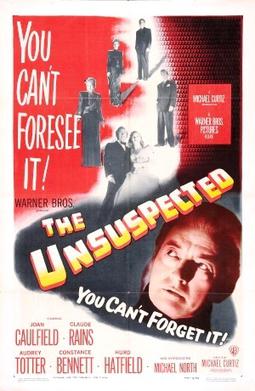

The Unsuspected has a delicious opening dripping with a foreboding chiaroscuro atmosphere. It’s the dead of night. There’s a woman on the telephone tucked away in a back room. The familiar face of Audrey Totter picks up on the other end of the line. She’s out enjoying herself at a club with some male company.

The Unsuspected has a delicious opening dripping with a foreboding chiaroscuro atmosphere. It’s the dead of night. There’s a woman on the telephone tucked away in a back room. The familiar face of Audrey Totter picks up on the other end of the line. She’s out enjoying herself at a club with some male company.

Someone emerges and descends on the flustered secretary. Moments later, she winds up hung from the ceiling — a grisly murder framed as suicide. For ’40s Hollywood, it doesn’t pull punches.

Since Totter is a consummate femme fatale, it’s easy to question what angle she could possibly have in this whole affair. We don’t have the answers, and so we must follow the rest of the film to find out; it’s a genuine pleasure to be afforded the opportunity.

If it’s not apparent already, we are in the hands of professionals with Warner Bros. stalwart Michael Curtiz directing a screenplay by Ranald MacDougall and the director’s wife, Bess Meredyth.

The film is dressed up nicely for a bit of noirish drama with the added benefit of the shadowy, gothic interiors when the story moves to the abode of one Victor Grandison (Claude Rain), a revered radio mystery performer who is reeling after the death of his secretary and the loss of his beloved niece who perished recently at sea.

Rains is an actor with such poise and regality, but building off his turn in Notorious, he plays another complicated figure. It’s a role worthy of his talents, and he anchors a packed menagerie of the usual suspects.

Totter as the sultry Althea always seems to take vindictive pleasure in playing the venomous harlot, and she’s just about one of the best from the era. With her arched eyebrows and intense eyes, she reflects the perfect epitome of an opportunistic, venomous vamp. Though it’s possible she only looks the part. Other people are willing to stoop to murder.

Her inebriated wet noodle of a husband (Hurd Hatfield) feels like a non-entity in comparison, and that’s precisely the point. Fred Clark always has a shifty authority about him, and he’s a close associate of Grandison. Over time, we realize he’s actually the local police detective, a handy man to have as a friend…

The ubiquitous Classic Hollywood heavy Jack Lambert is introduced in one lingering shot, looking out the window of some dive hotel window. What could he have to do with all of this? It’s difficult to implicate him immediately, but we know he’s waiting there for something.

Constance Bennett might just be the finest addition to the cast. She was the wit and experience like Eve Arden a la Mildred Pierce, both beautiful and able to trade banter and wisecracks with just about anyone. She lends a sense of levity to a movie that might otherwise feel oppressively dour. In some ways, she lives above the fray of everyone else, providing a kind of narrative escape valve for the audience.

If you think you already have a line on The Unsuspected, it’s a joy to mention it’s a movie full of perplexing wrinkles. A mysterious stranger (Michael North) shows up on their doorstep unannounced like a specter, and he asks to see Grandison. His next claim is even more outlandish: This young man, Steven Howard, was secretly married to Grandison’s niece Matilda.

Then, a dead person is resurrected like an apparition. Joan Caulfield’s character suffers from a cruel lapse in memory. What happened to her? I should have noted it sooner, but she has the aura like Gene Tierney in Laura, down to the portrait.

Like that picture, it’s a movie spent deciphering people’s motives; it feels like everyone is keeping secrets and no one wants to tell. Is it a case of elaborate gaslighting? It’s not unthinkable in the noir worlds of the 1940s, and Caufield is a ready victim, so sweet and innocent.

What are we to think? Who can we trust? In taxicabs, we find conspirators of a different kind — those trying to ascertain the truth behind a suicide. Because they know there is more than meets the eye.

Matilda returns to her home, lighting it up with the glow of her virginal white countenance in the dark recesses of the family mansion. It feels like oil and water. She does not belong there, but the story is still unresolved. There are several skin-crawling moments as Matilda is subjected to danger with a touch of Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941). Something’s not quite right, but perhaps her mind is playing tricks…We know she’s not crazy.

It might be low-hanging fruit, but the crucial nature of the antagonist makes the film feel like an early precursor to the Columbo series. Although we don’t know everything right away, eventually the audience is given the keys to the murder, and we must sit back in earnest to watch how they play out, from botched murders to car chases with the police toward the city dump.

I’m also intrigued by the trappings offered by murder mystery radio programs, and though they are used in other films like Abbott and Costello’s Who Done It?, to my knowledge, they aren’t as prevalent in Classical Hollywood as one might imagine.

There’s a delightful meta-quality with Grandison narrating plotlines that played out in the story around him, adding another perturbing layer for the filmmakers to play with. It feels especially fitting here, thanks to Rains’s mellifluous voice and the continued prevalence of mystery and true crime stories to this day. It seems like we still can’t get enough of them over 75 years later. The Unsuspected represents the best of Warner Bros. and the mystery genre, wrapped up in a movie that rarely gets talked about.

4/5 Stars

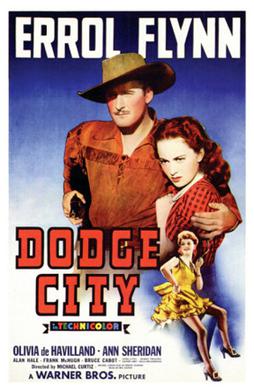

The year is 1866. The Civil War is over and anyone with vision is moving west. One such outpost is Kansas where the railway is replacing the stagecoach. It’s a world of iron men and iron horses. Because a place like the notorious Dodge City is a “town that knew no ethics but cash and killing.”

The year is 1866. The Civil War is over and anyone with vision is moving west. One such outpost is Kansas where the railway is replacing the stagecoach. It’s a world of iron men and iron horses. Because a place like the notorious Dodge City is a “town that knew no ethics but cash and killing.”

“My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan

“My father thanks you, My Mother Thanks you, My Sister Thanks you, and I Thank you.” – James Cagney as George M. Cohan