We are inserted, presumably, into a war picture courtesy of William A. Wellman, situated in WWI trenches. The downpour is compounded by the constant hail of bullets as a group of men conduct a near suicide mission. One of the soldiers, Tom Holmes (Richard Barthelmess) proves his heroics on the battlefield while his friend Roger dissolves in fear. But the battle leaves Tom, now a prisoner, with debilitating pain from some splinters of shrapnel lodged near his spine. He’s given morphine to keep it manageable.

He comes back from the war addicted. He gets the shakes at his bank job where he works under his war buddy Roger and the other man’s father. Tom is constantly in need of his fix and it just keeps on getting worse and worse.

Early on, the picture begs the question, how are heroes made? We turn them into near mythological beings and even if it’s well-vested that doesn’t mean that they consider what they did to be anything extraordinary. Imagine if it’s not deserved. Tom and Roger understand exactly what this is like. In the wake of a scandal and his ousting from the bank, Tom gets interned at a drug clinic only to come out a year later a new man ready for a fresh start.

It struck me that in a matter of minutes the film drastically shifts in tone, suggesting at first the dark shadows overtaking a picture like All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) only to come out unscathed and don the coat and tails of an industrial comedy-drama. I must say that while the former feels more akin to Wellman’s usual strengths, I do rather prefer the latter, though the picture doesn’t dare end there.

Wellman introduces us to our latest locale with a dash of humor delivered through an array of pithy signs adorning the walls of an old diner. But it’s the people under its roof that make it what it is. Pa Dennis (Charley Grapewin) is the most genial man you ever did meet and he would give you the shirt off his back if you needed it. His daughter Mary (Aline MacMahon) is little different though she chides her father for his loose finances.

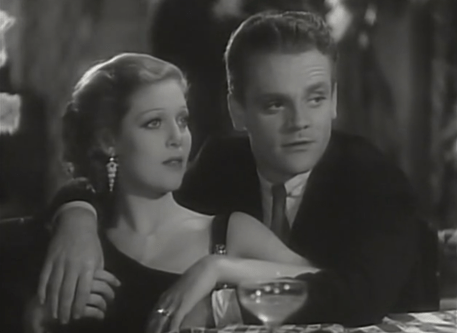

Still, her jovial hospitality charms Tom into striking up a conversation and considering renting a room from them. Meeting the disarmingly attractive Ms. Ruth Loring (Loretta Young) from across the hall all but seals the deal. Cue the music as Young enters stage right and let’s disregard it and just say she more than deserves the fanfare.

You would think the inventor with overt “Red” tendencies, adamant criticisms of capitalism, and a chattering habit like a squirrel would be a turnoff for prospective boarders. Not so. Soon Tom joins the ranks of the local laundry where Ruth also works forging a happy life for themselves.

The mobility of Heroes for Sale is another thing that struck me. It results from a different era but this is also very much a Depression picture in the sense that we are seeing what a man can still do even if times are tough as long as he has a strong head on his shoulders. Machinery is implemented not to steal work away from eager employees but to cut down on long working hours and increase output. All in all, it sounds like a thoughtful and humane objective.

But a heart attack leaves the company in different hands that are looking to work only in dollars and cents, not in humanity. Thus, it looks like Tom’s idealistic enterprising has been turned on its head, now completely sabotaged. All the folks who put their trust in him are bitter with the prospect of losing their jobs. Put out of business with their own funds. This same unrest runs through the pages of Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (1940) too as modernity begins to put out all outmoded methods standing in the way of so-called efficiency.

What we have here is a populist picture daring to show the plight of the people. Richard Barthelmess is an affecting lead because he seems almost unextraordinary. His voice is steady and calm. He’s not unkind. But there’s an honesty to him that asserts itself. The fact that he gets a bum steer and takes it without so much as a complaint speaks volumes so he doesn’t have to.

Heroes for Sale feels like a micro-epic if we can coin the term. It’s ambitions somehow manage to be grandiose as it sweeps over cultural moments like WWI and The Depression which underline further social issues including heroism, drug abuse, communism, and worker’s rights. All done up in a measly 71 minutes. Look no further than the standoff between an angry mob and the riot squad for squalid drama. This is no minor spectacle. Nothing can quite express the anguish watching Young frantically run through the violent frenzy in search of her husband.

There is no excuse if this is the standard we put longer films up against. Not a moment seems wasted. Yes, it goes in different directions. Yes, it feels like a couple different films and yet what connects it all is this abiding sense of Americana. Themes that resonate with folks who know this country and its rich history made up of victories and dark blots as well. Most brazenly it still manages to come out of the muck and the mire with a sliver of optimism left over. Heroes For Sale is no small feat.

4/5 Stars