The introduction of the main character Jerry Mitchell (Casey Siemaszko ) feels fairly standard and in line with Ferris Bueller, Say Anything, or any of its brethren from the ’80s. Late for school. Dirty shirts strewn about. Simultaneously zapping pop tarts and wet clothes in the microwave. Flat tires and your kid sister hands you a diet Coke to gargle the toothpaste you just finished brushing with. It’s quirky enough to give us some sense of who we’ll be following for the next hour and a half without straying too far from genre convention.

The introduction of the main character Jerry Mitchell (Casey Siemaszko ) feels fairly standard and in line with Ferris Bueller, Say Anything, or any of its brethren from the ’80s. Late for school. Dirty shirts strewn about. Simultaneously zapping pop tarts and wet clothes in the microwave. Flat tires and your kid sister hands you a diet Coke to gargle the toothpaste you just finished brushing with. It’s quirky enough to give us some sense of who we’ll be following for the next hour and a half without straying too far from genre convention.

Still, all of this handy exposition feels a bit like a misdirect or at least suggests up-and-coming director Phil Joanou started out with one movie in mind and came up with something else along the way. More on that momentarily.

Jerry is a likable, if innocuous, dweeb we can probably imprint ourselves on and his high school, located in Odgen, Utah definitely doesn’t have the Hollywood glam. It lends itself to a different kind of visual milieu we can appreciate. All the adults in the movie for the most part are only totems to hang necessary impressions and sentiments on.

Jefferey Tambor is the closest to an actual character as a teacher who entrusts Jerry to run the student store and marvels at what a profitable business he’s managed. Otherwise, most of the authority figures and even government agents (how they always have time for teenagers is beyond me) feel like caricatures without too much premeditation.

Despite some promising introductions, most of the friends and female characters feel fairly empty no fault of their own. Jerry’s sister Brei has a chatty wit about her but essentially disappears from the movie popping up only when required.

There’s his thoughtful if slightly ethereal girlfriend (Annie Ryan) whose eyes grow luminous as she speaks candidly about spirit animals and her spirit “guide” Ethan. Don’t ask me to explain. And because Franny’s the brunette (yes, her name’s Franny), there’s also the untouchable blonde goddess Karen (Liza Morrow) who exists as a figment rather than a full-bodied character. She’s always ready to induce traffic accidents and seismic heart palpitations in our fearless hero.

Although it is Jerry’s story, it almost feels like it’s too much about Jerry and his inner psychology. He’s not the most intriguing part of the picture though we do need him as a conduit. Perhaps more could have been built out of his relationship and even his alienation from others. But it’s also necessary to take a moment to consider the movie’s tone and inspiration.

I’m not sure how to parse the fact from the fiction (this oral history is the best resource available) but supposedly this is one of the films Steven Spielberg requested to have his name taken off as an executive producer. It probably comes down to how dark it becomes though even this might lack the ring of truth.

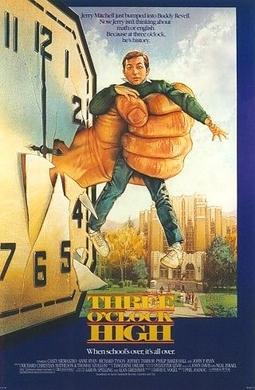

Although it’s easy to label Three O’Clock High as a high school rendition of High Noon, it actually stands more in line with Martin Scorsese’s After Hours from a couple years prior. Given this comparison, Spielberg’s purported surprise would make more sense because this premise has all the potential hallmarks of a traditional ’80s teen movie.

Like its predecessor, I find it drags in the middle using time a bit like After Hours to give in to its most absurd and surrealist tendencies as Jerry’s world dissolves and slowly closes in around him.

One could easily say Soho in the prior film has been distilled down to the school corridors and classrooms Jerry is tied to as he sweats the hours ’til his inevitable annihilation. It does make it feel like Gary Cooper’s Will Kane when evoking the limiting factor of ticking clocks.

However, a venture to the principal’s office features the décor and camera angles fit for The Bates Motel. Later Jerry’s chased down by a security guard in the parking lot. Wasn’t the man in After Hours pursued by an angry ice cream truck? Otherwise, there’s a ghoulish school assembly accentuated by Tangerine Dream’s quintessential ’80s synths and any number of preliminary bouts laying the groundwork for his dreaded showdown.

We have yet to mention the movie’s primary villain whose psychotic reputation more than proceeds him, whispered throughout the halls and steps of the school as it is. The only reason there’s even a movie stems from Jerry’s position at the school newspaper. He’s given the unenviable assignment to profile Buddy Reveill (Richard Tyson) and one urinal encounter makes them mortal enemies for life. Nothing he can do can put off the unavoidable.

The ending does deliver on some of its payoffs by casting off any sense of moralism for a good old-fashioned bloody smackdown between good and evil without a ton of didactic consequences. Law and order are thrust aside as the adolescent masses cheer and rage sensing the brass-knuckled fury in the air. I did begin to wonder if in 80s-era America this hulking villain was a stand-in for fascist or authoritarian regimes. It’s of little importance.

Because this is only an afterthought as Jerry faces Goliath and is subsequently saved by the student body in a deus ex machina a la It’s a Wonderful Life. The lesson: It pays to stand up against tyranny and oppression in the school parking lot. More important still, boyish fantasy is kindled and nothing else exists beyond this singular moment in time. It is a kind of wish fulfillment for young males of a certain age.

Whether it was Joanou’s inspiration, screenwriters Richard Christian Matheson & Thomas Szollosi, or more likely a confluence of everything, Three O’Clock High feels more like a cult curio than an unadulterated classic. That’s not meant to be a slight, nor a total dismissal. It’s not Scorsese (it’s not even Speilberg). But it shouldn’t have to be. It deserves to be taken or left on its own terms as another addendum to the ’80s teen movie canon.

3/5 Stars

Get Out seems like a simple enough premise. Ridiculously simple even. We’ve seen it millions of times in rom-coms or other fare. It’s the fateful day when the significant other is being taken to meet the parents. Whether they pass this test will have irreversible repercussions on the entire probability of the relationship’s success. Maybe that’s a tad over the top but anyways you get the idea as Rose (Allison Williams) drives her boyfriend Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) to meet her parents.

Get Out seems like a simple enough premise. Ridiculously simple even. We’ve seen it millions of times in rom-coms or other fare. It’s the fateful day when the significant other is being taken to meet the parents. Whether they pass this test will have irreversible repercussions on the entire probability of the relationship’s success. Maybe that’s a tad over the top but anyways you get the idea as Rose (Allison Williams) drives her boyfriend Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) to meet her parents. From the haunting opening notes of a lullaby to the otherworldly aerial shot floating over New York, Rosemary’s Baby is undeniably a stunning Hollywood debut for Roman Polanski.

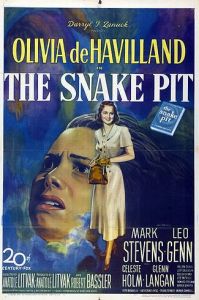

From the haunting opening notes of a lullaby to the otherworldly aerial shot floating over New York, Rosemary’s Baby is undeniably a stunning Hollywood debut for Roman Polanski. There is a lineage of psychological dramas most notably including the likes of Shock Corridor and One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest. But one of their primary predecessors was The Snake Pit which is a haunting, inscrutable and thought-provoking film in its own right.

There is a lineage of psychological dramas most notably including the likes of Shock Corridor and One Flew Over the Cuckoos Nest. But one of their primary predecessors was The Snake Pit which is a haunting, inscrutable and thought-provoking film in its own right.