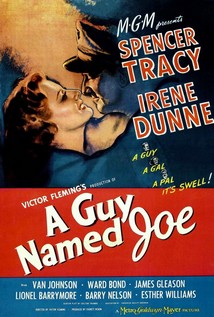

Although I would probably choose 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, a movie also penned by Dalton Trumbo and featuring Spencer Tracy and Van Johnson, there are numerous reasons to search out A Guy Named Joe.

Although I would probably choose 30 Seconds Over Tokyo, a movie also penned by Dalton Trumbo and featuring Spencer Tracy and Van Johnson, there are numerous reasons to search out A Guy Named Joe.

This was Van Johnson’s first starring role, allowing him to craft a stage presence that would only become more self-assured with time. It nearly got derailed by a gruesome car accident that purportedly left him with a plate in his forehead. And yet out of this came one of the most popular young stars of his day.

Also, Irene Dunne, one of the often unsung comediennes and finest dramatic actresses of the 30s and 40s, gets the opportunity to show her stuff opposite Tracy. I will never miss an opportunity to see her because she’s easy to rate next to other luminaries like Katharine Hepburn and Barbara Stanwyck.

Some well-informed viewers might also be aware that Steven Spielberg transposed the action to the 1980s with his light remake, Always, starring Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, and a cameo by Audrey Hepburn. It’s easy to surmise the later film misses out on the historical context, making A Guy Named Joe about something immediate.

Pete Sandidge (Tracy) is your stereotypical loose cannon, hotshot who’s always receiving the ire of his superior (James Gleason). Nevertheless, the two of them maintain a playful game of cat and mouse because deep down, they both know they’re invested in the same cause.

Pete’s also reunited with his effervescent girlfriend, the alliterative Dorinda Durston (Dunne). She also flies planes, albeit not in combat. All the lovey-dovey grousing and such isn’t new, but between Tracy and Dunne with Ward Bond as the third wheel, it’s inherently watchable. They channel a love-hate relationship: getting sore at each other and making up in a passionate reverie.

Tracy and Dunne aren’t normally associated, and yet watching them together is an immeasurable pleasure because they have a grand capacity for bits of sly humor and shared humanity, elevating the material above mediocre fare.

The movie also boasts some impressive and truly immersive aerial sequences as Pete leads his men on one of their perilous bombing raids against the enemy. This latest mission also signals a shift in the story; a fatal crash occurs, and Pete’s last gasp of heroism means he’s good and dead.

He’ll spend the rest of the movie as a guardian angel, though he’s more like a ghost. So A Guy Named Joe quickly shifts from a purely WWII picture to another film in the cinematic angel canon (It should come as no surprise that producer Everett Riskin also worked on Here Comes Mr. Jordan).

Pete walks through the clouds of the afterlife not with a harp but a decidedly more militaristic objective. There’s a pointed weightiness in casting by making Lionel Barrymore the CO of the heavenly realms. He passes down to the newly deceased his marching orders: He will be serving as an unseen co-pilot to some new recruits.

Again, the movie shifts to focus on Don DeFore and Van Johnson as two problem flyers still wet behind the ears. Johnson plays a wealthy, if diffident, young man named Ted Randall who can barely keep his plane airborne. Tracy shudders at the future of the war in the hands of such callow talent, but he tries to get them up to speed anyway, albeit subconsciously.

These sequences are rather mundane because, unlike other stories in the angel canon, Tracy’s connection to the real world is very thin compared to Claude Rains, Cary Grant, or even Henry Travers in It’s a Wonderful Life.

The movie picks up again when Van Johnson is on the ground and progressing in confidence. We see an early pairing of Johnson and a nearly unrecognizable Esther Williams, perhaps because she’s not robed in Technicolor and a swimsuit. They share a dance, and he extends an act of kindness to a homesick soldier.

Tracy is forced into being an observer in the physical sense, and somehow, the passivity doesn’t suit him. It’s good for a few gags and dress downs of former friends and colleagues who can’t hear him, but it becomes a bit of a gimmick.

And after waving a movie about Tracy and Dunne in front of us, it tries its best to stitch together something between Dunne and Johnson that just feels a bit disjointed and forced.

Still, A Guy Named Joe has these compartmentalized moments of human connection, laughter, and tears, making it more than worthwhile. You get the sense of the war years, the transience that these young men and women felt on so many accounts. Be it the death of friends and comrades, or even the distance of loved ones so far away. Everything spells heightened emotions.

To its credit, I never thought I would see a movie with Irene Dunne breaking ranks to fly a bombing raid solo and drop a payload on a Japanese target. There’s something both ludicrous and oddly progressive about it, never mind how it seems to muddle the collectivist themes the movie seems to be aiming for.

However, the fact that there can be no catharsis for Tracy and his lost love might be a final lesson about the war years. It is a dream and a desire that cannot be fulfilled. In its wake, Johnson and Dunne must chase after each other instead in a swelling romantic ending without any earthly consequences as Spence disappears into the distance. It’s a pale imitation, but it will have to do.

3/5 Stars

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France.

WWII is always a fascinating touchstone of history because it has some many intricate facets extending from the Pacific to the European Theater to the American Home Front and so on, each bringing with it unique stories of everyday individuals doing extraordinary things. One of the best-kept secrets is the 442nd Infantry Division later joined with the 100th and effectively making the first all Japanese-American fighting unit which served over in Italy and France.