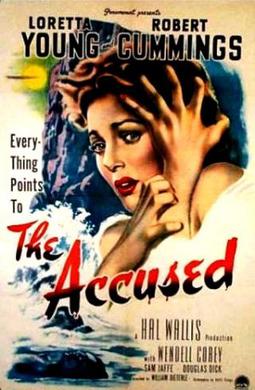

Loretta Young must own a pair of the most luminous eyes in the history of Hollywood, and in black and white, she’s incandescent. More important than that, she’s one of the great sympathetic heroines of Classic Hollywood. In The Accused, she plays both a woman in danger and a working professional. They don’t have to be mutually exclusive, and it makes for a far more nuanced character, especially for the post-war 40s.

Loretta Young must own a pair of the most luminous eyes in the history of Hollywood, and in black and white, she’s incandescent. More important than that, she’s one of the great sympathetic heroines of Classic Hollywood. In The Accused, she plays both a woman in danger and a working professional. They don’t have to be mutually exclusive, and it makes for a far more nuanced character, especially for the post-war 40s.

Like poor Ida Lupino in Woman in Hiding, we meet her in the dead of night on the road. It’s evident she’s frantic and on the run from something. She gets picked up by a truck driver, though she’s not much for conversation, and he lets her off without much consequence.

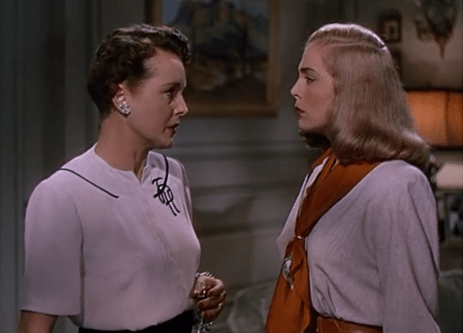

A flashback introduces her pre-existing life as Dr. Wilma Tuttle, a professor of psychology at an unnamed university in L.A. It’s finals week as students take their exams and classes wind down.

We get an inkling of drama as we watch the wordless interaction between the fidgety teacher with a leering male student, mirroring her every move and, no doubt, turning in a Bluebook analyzing her own personal psychoses from biting on pencils to tugging on her hair. It’s a queasy relationship because, although she’s in a position of authority, she also seems helpless to do anything.

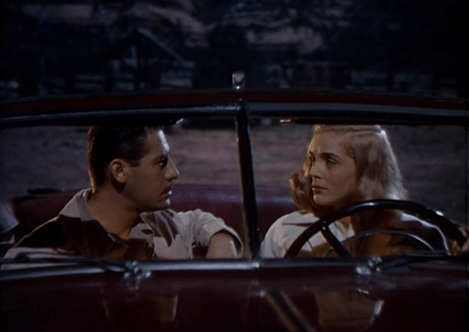

Douglas Dick does well as the slimy, if charismatic, co-ed who looks ready to entrap his teacher; he’s a kind of skeevy-eyed homme fatale playing teacher’s pet and coaxing his favorite instructor along — first offering her a ride home and then stopping by the seaside in Malibu.

Without using too much equivocation, it becomes a movie about assault and trauma, with the feminine victim becoming the accused, much like Anne Baxter in Blue Gardenia. There needn’t be a movie, but in the 1940s, she operates out of a position of fear in a predominantly male world.

Wilma’s internal monologue gets a bit oppressive, becoming a monotonous crutch, but the cavalcade of performers who come alongside Young are a worthwhile reason to stay the course. Robert Cummings and Wendell Corey aren’t showstoppers necessarily, and still, they have the prerequisite appeal to see them through the career of a reliable actor in Hollywood.

We meet lawyer Warren Ford (Cummings) and Lt. Ted Dorgan (Corey) together at Malibu police headquarters. The former was the boy’s guardian, and the policeman is investigating the case. After the boy’s body washed up on the beach, it was deemed an accident and no foul play.

No fingerprints were found in the car. Immediately, as an audience, we’re doing our mental calculations. Could this be, or is it merely a glaring plot hole? I’ll save you the trouble. Young was wearing gloves as a true lady does in the 1940s. Or else she wiped them…

The film’s asset comes with how it ties all of its primary relationships into twisted knots, all in the name of interpersonal tension. Warren has some personal connection with the deceased, but he quickly becomes enamored with the lady professor, and why wouldn’t he be? They effectively mix work and play, with Cummings being the smooth silk to Corey’s abrasive sandpaper approach.

In its latter half, The Accused becomes a Columbo episode from the inside out. We have our Hollywood star. There’s an opening prologue before the police get involved, and she falls in love. She also begins to feel trapped by what otherwise would be everyday occurrences as she tries to protect herself and cover her tracks.

One of her pupils is a primary suspect. She’s also requested to drop off the dead boy’s Bluebook, which might incriminate her. The truck driver who picked her up in the dead of night is called in as an eyewitness. Then, there’s the business of a missing note that she left for the dead boy and then misplaced. She must find and incinerate it.

Corey’s character is difficult to read. There’s something horrid about him, far worse than his incarnation in Rear Window, and yet he tries to play it off as an act or all part of the game he’s embroiled in on the daily as he does his job. It’s a bit of a curious surprise to see both Henry Travers and Sam Jaffe taking up positions in the police lab. There’s a rational inevitability about the work they do.

Wilma feels the heat, and a date at a boxing match brings out all her latent traumas to the surface again as she transposes the boxer in the ring with the boy she killed. In one sense, there needn’t be a movie because she is a victim, though she digs a bigger hole for herself.

Ultimately, the movie’s denouement is open-ended. The courtroom proceedings are just beginning, and her fate is far from settled, but as we stare into the dazzling eyes of Loretta Young, it’s easy enough to know she will beat the rap with a hedge of innocence around her.

If you dwell a little too much on the implications, the optics that Dorgan also observes might be a flaw in the justice system — if sympathetic appearances are taken as everything. However, in a movie about a woman who is assaulted and then plays the culprit out of fear, it’s at least par for the course.

There’s also a couple of oddities: Corey flirts with her in the courtroom, and Cummings is effectively defending her for killing his “nephew,” though they weren’t close. And still, Corey’s impish sense of humor and Cummings’s passionate orations for his beloved don’t change the bottom line.

This is Loretta Young’s movie, and even as she plays an intelligent woman often hassled and infantilized by the world around her, there’s something so winsome and generous about her performance. The noir elements burn off to make it a story of reclamation and vindication of a life. If you go digging, it does feel like a movie moderately ahead of its time, courtesy of screenwriter Ketti Fring and Young, respectively.

3.5/5 Stars

The interesting part is that as an audience we are fully involved in this story. We see much of the picture from Jefferies’ apartment, because there is no place to go, and so we stay inside the confines of the complex. In this way, Hitchcock creates a lot of Rear Window‘s plot out of actions occurring and then the reactions that follow. We are constantly being fed a scene and then immediately being shown the gaze of Jefferies. It effectively pulls us into this position of a peeping tom too. Danger keeps on creeping closer and closer as he discovers more and more. The narrative continues to progress methodically from day to night to the next day and the next evening.

The interesting part is that as an audience we are fully involved in this story. We see much of the picture from Jefferies’ apartment, because there is no place to go, and so we stay inside the confines of the complex. In this way, Hitchcock creates a lot of Rear Window‘s plot out of actions occurring and then the reactions that follow. We are constantly being fed a scene and then immediately being shown the gaze of Jefferies. It effectively pulls us into this position of a peeping tom too. Danger keeps on creeping closer and closer as he discovers more and more. The narrative continues to progress methodically from day to night to the next day and the next evening.