A voice of God with a certain newsreel ethos sets the scene. California’s Imperial Valley. An area renowned for its robust agricultural industry. The Bracero Program, that brilliant reflection of U.S.-Mexican relations during the war years and beyond. However, if this scenario sounds too simplistic and squeaky clean, it soon gets slightly more intriguing in consideration of the border.

You have illegals jumping the fence to get into the U.S. and numerous egregious perpetrators of human suffering and injustice looking to take advantage of the situation by any means possible. Indigenous Bandidos are looking to murder and pillage a la The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948) and their savagery terrorizes the countryside. Then, there is the clandestine trafficking of labor, another real-world problem portrayed in cinematic terms.

Because Border Incident is pronounced a composite case of real life and hard facts. Like T-Men before it, the introduction leaves me rather skeptical. It does feel like reality is still being sculpted, not only for the movies but in a manner that the heroes and villains can become more easily definable.

Instead of a trail of counterfeit bills, it’s all about finding out the route of illegal transportation into the country. But regardless of my qualms, it’s extraordinary for Ricardo Montalban to get such a hefty and prominent part in a picture. There’s no question he’s the standout, at least as far as the heroes are concerned, playing a brave and charismatic Mexican agent, Pablo Rodriguez, who is tasked with uncovering the smuggling at its source. His American counterpart is American Jack Bearnes (George Murphy) who is brave but hardly as compelling.

There are, however, plenty of villains to fawn over as with any respectable noir. Charles McGraw is an ornery enforcer who takes no flack and pushes the impoverished Mexicans around like chattel. Being wary of the border patrol in Indio, he’s not above dumping their cargo in the Salton Sea if they have to. It’s a chilling illustration of his disreputable nature.

Jack Lambert is always game as a sneering heavy and Howard Da Silva also has a mug made for villainy. However, in this case, he’s actually a big deal — the untouchable mastermind of this entire operation — it’s the men below him who get their hands dirty.

While Rodriguez is embroiled right in the pit of the harrowing operation, befriending a sympathetic countryman named Juan Garcia (James Mitchell), it is the American agent who works from the top down; he gets an alias as a criminal on the lamb and makes contact with the big man. They look to set up a mutually beneficial business transaction, a load of visas for heaps of cash.

If the narrative structure leaves something to be desired, there’s nevertheless an impeccable framework for Mann to implement his unsentimental brand of filmmaking. In a textbook example, there’s a moment where Lamber’s fingers get crammed in a truck window — as the braceros try to flee — only to get pushed off the speeding vehicle and potentially hurtled to his death. The uncompromising imagery is only to be surpassed when a wounded border agent is squashed to smithereens by a tractor, literally dwarfing the frame. It’s this sense of suffocation even in wide open spaces.

The glorious tight angled close-ups are only one facet to the film, accentuating this sense of constraint just as the extraordinary tones of John Alton, in essence, cloak the space in a noose of supreme darkness. For a film about men trying to flee authorities crossing cultural borders, there’s hardly a better visual method of conveyance possible.

Raw Deal is still the gold standard of Anthony Mann film noir with T-Men and then Border Incident falling a rung below. Mostly because the mechanism created for the plot feel flat, and yet everything Mann and Alton touch really is dynamite, with the most gorgeous tones, equally stylistically dynamic. It’s a killer one-two punch and all business as usual for director and cinematographer.

On this front, as a merely technical and formalistic endeavor, Border Incident is superb and a darn good docu-noir. In the closing moments, Montalban gets swallowed up by quicksand, fighting for his life against adversaries, and fistfights and gunshots abound on all sides. These lightning rods of drama are appreciated.

Unfortunately, it keeps the same framework that now in present days looks more propagandistic and heavy-handed then authentic storytelling. We find ourselves with a certain rhetoric about living under the protection of two great republics and the bounty of God Almighty.

Of course, there’s no mention of the Zoot Suit Riots and the perpetration of racial violence, because that was too close to home and does not fit into a handy framework for a public service announcement storyline such as this. Instead of chalking all problems up to cold, capitalistic men in suits with greedy underlings, we must look at a social system that breeds bigotry as much as it does inequality. Admittedly, I am not one with the right answers but nonetheless, I am curious to know how we move forward from a film like this.

3.5/5 Stars

The Curse of the Cat People feels like entering a storybook only to find ourselves in Tarry Town near Sleepy Hollow. Fittingly, we are placed with a group of kindergarteners who have come with their teacher to frolic and enjoy a field trip to the place brought to life in the tall tales of Washington Irving.

The Curse of the Cat People feels like entering a storybook only to find ourselves in Tarry Town near Sleepy Hollow. Fittingly, we are placed with a group of kindergarteners who have come with their teacher to frolic and enjoy a field trip to the place brought to life in the tall tales of Washington Irving. “What a hobby to pick: authority.”

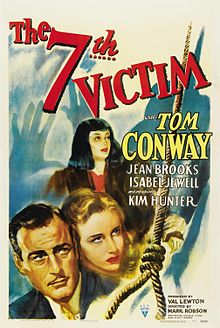

“What a hobby to pick: authority.”  What a picture for Kim Hunter to have come into her own (and Mark Robson for that matter). The 7th Victim is a chilling gem, and the motor to move the story forward is an audacious girl, Mary Gibson (Hunter), who makes a decision to leave her boarding school of stain glass and angelic choirs, to search after her missing big sister.

What a picture for Kim Hunter to have come into her own (and Mark Robson for that matter). The 7th Victim is a chilling gem, and the motor to move the story forward is an audacious girl, Mary Gibson (Hunter), who makes a decision to leave her boarding school of stain glass and angelic choirs, to search after her missing big sister.

The film commences brilliantly as Frances Dee can be heard in voiceover with almost fond recollection, matter-of-factly stating, “I Walked with a Zombie.” The way she expresses it immediately debunks anything we might think from an admittedly exploitative title. Producer Val Lewton does not settle for a straightforward slapped together horror flick.

The film commences brilliantly as Frances Dee can be heard in voiceover with almost fond recollection, matter-of-factly stating, “I Walked with a Zombie.” The way she expresses it immediately debunks anything we might think from an admittedly exploitative title. Producer Val Lewton does not settle for a straightforward slapped together horror flick.

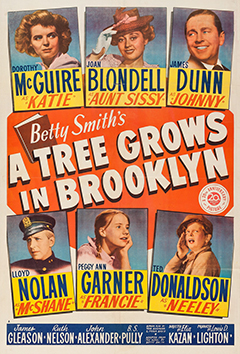

The reveries of a Saturday afternoon in childhood are where A Tree Grows in Brooklyn chooses to begin and it proves a fine entry point, giving us an instant feel for the world the Irish neighborhood of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Its contours are impoverished, even harsh, but also richly American.

The reveries of a Saturday afternoon in childhood are where A Tree Grows in Brooklyn chooses to begin and it proves a fine entry point, giving us an instant feel for the world the Irish neighborhood of Williamsburg in Brooklyn. Its contours are impoverished, even harsh, but also richly American.