There’s no other way to put it. The West Point imagery of The Long Gray Line is smart from the outset, and if nothing else, it instills this sense of admiration in the military sharpness of this storied institution. However, although this is a hagiography from John Ford, it feels more full-bodied than a typically blasé biopic.

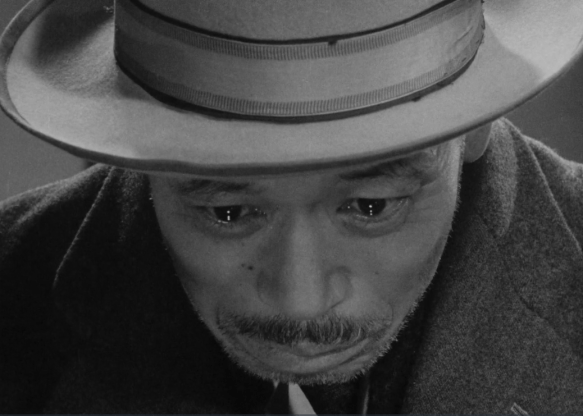

For one thing Tyrone Power, more so than an Errol Flynn or some of the other earlier idols, proved his candor for meatier roles that might showcase what he could do. And between the likes of Nightmare Alley and Witness to the Prosecution is a picture that probably gets less fanfare written about it. His portrayal of Martin Maher, a lifelong West Point man, is both endearing and surprisingly comic even as his brogue is quick to take over the picture.

Because it is a biography as only John Ford could manage it. He employs broad humor from fisticuffs to falling plates to brawls in the manure pile while assembling all his surrogate screen family together — paying his usual homage to his Irish roots in the process. If none of this particularly piques your interest, it’s probably not for you. Because if we can say anything about The Long Gray Line, there’s no doubt about it. This is another quintessential John Ford picture.

West Point is fit for Ford because you have this underlying sense of tradition, honor, and camaraderie. The drills, men dressed in their uniforms, and the very architecture produces wonderful elements for Ford to exercise his glorious stationary wide shots. However, it’s not merely about composition but motion and people being galvanized together through shared experience, be it song, dance, or the rigors of military drills.

Moreover, it covers such an expansive time frame and yet it feels free from a lot of the typical narrative pitfalls. There’s a general sense it’s more content with the details and observations of life than stringing together a story of dramatic event after dramatic event each comprised of their own life-altering meaning.

Instead, what we see is totally fluid without needing to explain itself, and as we’re not dealing in huge historical events, but one man’s extraordinary life, this lassitude works quite well.

It considers time, acknowledges how life is ordered by time but is never a slave to it. The guiding light is a meditation on tradition more than a pure devotion to realism. Mind you, there are a few winks with the camera to Pershing, Knute Rockne out on the football field, even Harry Carey Jr. portraying a young version of incumbent president Dwight D. Eisenhower.

We also methodically follow the train of Marty’s life from a “fresh of the boat” Irish immigrant to a bumbling waiter, an up-and-coming athletic coach, and then a corporal training up the youthful cadets and helping instill in them the pride and responsibility of their station.

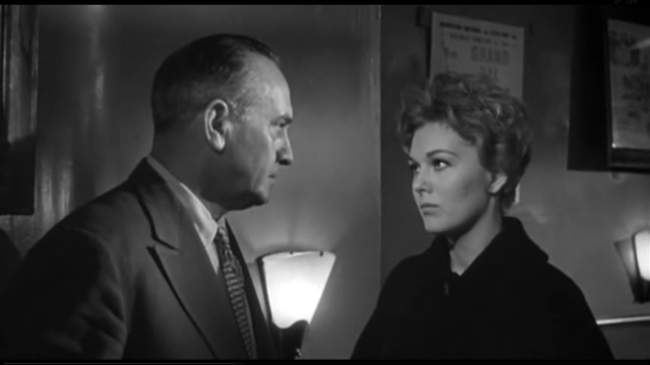

Soon after Marty’s arrival, Mary O’Donnell (Maureen O’Hara) arrives from the old country to serve as a cook for a local family. Ford delivers their so-called meet-cute in such a curious manner it could be out of a silent movie. For someone known for talking so passionately, O’Hara nary utters a word, instead, punting one of Marty’s boxing gloves while he trains up the lads in the art. Of course, he can’t help but keep sneaking glances back at her. It’s the beginning of a lifelong love story.

With John Wayne not attached to the picture (Ford wanted him), some of Ford’s other usual suspects get their due chance to shine. Ward Bond is a fitting embodiment of the gruff but effectual Master of the Sword, Captain Koehler, who invests in Marty. The classes of cadets are sprinkled with the likes of Harry Carey Jr. and Patrick Wayne. While Old Man Martin (Donald Crisp) arrives from Tipperary soon thereafter.

Although not a Ford regular, the cast includes Robert Francis, who was Harry Cohn’s answer to the new rebellious class of actors, the antithesis of James Dean and his ilk. Sadly Francis’s career was no less tragic. The rising actor only appeared in 4 movies before dying in a plane crash in 1955. This would prove to be his last project.

The last impression of The Long Gray Line suggests how Martin is as much an institution as the institution itself. In this regard, one’s memories are quickly drawn to Mr. Chips because Marty Maher feels like an analogous figure for the halls of West Point. Ford shows his knack for visual articulation in how he instills similar themes.

Instead of a deathbed pronouncement of a life well-lived, we see it all in action. Marty is older now, white-haired, and coming up on 50 years with the school. He has old friends doting over him, and new ones helping set up the Christmas tree. They put up the decorations and busy themselves in the kitchen

Again, it’s this constant motion and movement leading us toward greater communal well-being. Where we are reminded how much stronger we are together and how much comfort can be gleaned in time spent with others doing all manner of things.

Surely Ford could not have meant any of this and yet that’s the beauty of it because it all feels very organic in nature — organic to how we live as human beings — and bearing the truth of real life. It’s not just the momentary yuletide cheer that draws me back to It’s a Wonderful Life, it’s the community and Ford gives Marty a hero’s send-off full of poignancy (and “Auld Lang Syne”).

Although he’s come a long way from Tipperary, the verdant greens of the landscape feel like an immigrant’s reminiscence of The Quiet Man now on opposite shores, but no less resplendent. His roots and the aspects of his character and the family he holds dear are never far away.

Watching the ending, as a grand exhibition is put on in Marty’s honor, is spectacular unto itself. There is this gravitas similar to The Quiet Man or even the final parasol twirls of Rio Grande where we feel like we have taken part in something substantial just in studying the faces of our leads from their regal posts. They feel like giants on the screen.

After all, we’ve been privy to an entire lifetime and The Long Gray Line keeps on going. True, there’s a temptation to see this as a monotonous even a depressing thing — how time marches on and how there will always be new recruits to replace the old. People leave. Even Marty Martin was buried on the grounds after his 50 years of service.

However, in the hands of Ford, these genuine realities of life somehow have a definitive meaning that feels worthwhile and grand. It’s by no means naïve in its perspective, and yet it seems to grasp the meaning, even the goodness, and the dignity, in such a place. It’s made up of the people as much as any kind of ideals.

What makes the film stick for me is how it is not a true cradle-to-grave epic nor is it a war picture. Ford had been in combat and had seen the Battle of Midway for goodness sakes. He wasn’t some wide-eyed idealist high on the glories of war. And yet his penchant is to still memorialize them in some manner through a lens he can understand, namely, the man, the myth, the legend: Marty Maher.

4/5 Stars