The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.

The action begins with a chase of sorts, except with the men pursuing a buckboard, carrying a woman and a young boy, it’s more like a game of cat-and-mouse. As a Native American maiden and a pretty one at that, they look to have their way with her. A horrible incident follows, and it’s a fairly frank depiction for the 1950s.

Meanwhile, a local Marshall (Kirk Douglas) can be found regaling the kiddos with a story about the olden days, 10 years prior. It’s strangely light in contrast to the preceding scene. This is precisely the point because never again will we see the Marshall with such a jovial demeanor. We must wait only minutes to comprehend how our pieces fit together. Because this young boy, his son, races to call upon his father. It is his wife who has been brutally ravaged and left for dead.

There are only a couple of clues to go by. The first is a deep scar on the cheek of one of the perpetrators. His wife did not give up without a fight. The second is an abandoned horse with an ornate saddle. He knows it well. It belongs to an old friend: cattle baron Craig Belden.

Because the man who raped Catherine Morgan was Belden’s gutless son. The other man was one of his many hired hands. If not already clear, the dramatic dilemma becomes even more tenuous. The Marshall wants justice and resolves to pay his old buddy a fateful house call.

Under any other circumstances, these two men would be meeting for a drink to wax nostalgic about old times — the glory days — because it’s true things were different back then. As we have a habit of doing, we memorialize our youth, and the friends and experiences we gird around us as young men commonly follow us our entire lives.

But now they must factor in their current lives. Morgan’s wife is dead. Belden’s last kin is his boy Rick (Earl Holliman). Family is everything to the two of them, and it finds them at odds across most fragile lines.

Soon enough, this western finds its tracks along with the lumbering steam engine barreling through the local town. It’s the age-old format gleaned from High Noon and 3:10 to Yuma. A showdown is inevitable. The train is the method by which locals keep time. It’s is a destination, a symbol, and a way in which to move from here to there. It brings people in and takes them out. Sometimes to leave and find a new life. Sometimes to end someone else’s life.

And yet, as alluded to already, this western is far more personal. This is its strength because Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn, as old chums, are pitted against each other under very unpleasant circumstances. But the story also requires someone who can stand up to Kirk Douglas as far as acting chops and screen presence go.

If not exact equals, they keep the playing field level based on their enduring differences. Neither is looking to budge. One, a marshall with an unassailable will. The other, a cattle baron who owns the entire town. They represent justice in two divergent forms, as individuals enacting the law as they see fit, whether through dictatorship or vigilantism.

The Marshall tries to drum up some allies in town. The stand-in for sheriff is always about taking the long view. That is, whatever will let him keep his craven neck alive. Realizing the whole town’s on Belden’s side, he settles in for the long haul, taking the young upstart prisoner and holding up inside an upstairs hotel room — his captive manacled to the bedpost. The stakes are set firmly in place, milking the tension to the nth degree. We know what must go down if no one budges.

Earl Holliman’s not necessarily as adept at mind games as Robert Ryan in The Naked Spur or Glenn Ford in 3:10 to Yuma, but he proves he can play the jerk. He’s the detestable combination of an entitled rich kid and a spineless loser.

It’s a misnomer to say there are no sympathetic figures. Morgan makes the acquaintance of one on the train into Gun Hill. She too has a past with Belden. In a town and theatrical landscape literally dominated by men, Linda (Carolyn Jones) has to be strong and a bit of a pragmatist. For these very reasons, she wants to see the Marshall succeed in his foolhardy task.

So, in fact, he has one minor ally for the very reason she’s not completely against him, though she’s not looking to play hero. Nevertheless, she admires a man with manners and the moral compass to hold doggedly to his principles. In a passive way, she’s in his corner, if only because he has the gumption to stand up to her old beau. However, she comes to be more than just a mere observer. Linda gives him his lifeline for bringing his crazy plan to fruition.

With tension mounting, he leads his prisoner out of the hotel with the whole town watching, all the guns trained on him, and the 9 o’clock train arriving just as planned. He marches out with his shotgun square on his prisoner’s quivering jaw. He’ll get it if anyone moves and so we have a contentious stalemate. By some crazy circumstance, he might find a way to achieve justice yet. Because, again, the train is a symbol. It reflects what he might still be able to do if he can only get there.

In the end, it barely matters. It’s a partial spoiler yes, but this was always a story about relationships more than anything. The draw must blow up somehow before reverting to its most crucial point of conflict. It’s all over and yet we’ve reached the inevitable point of no return. A hesitant Marshall is called to draw on his best friend. He doesn’t want this.

But Belden is an equally proud man, and he lives by a certain creed of western masculinity. You must face a man for any personal affront to your being. There is no other way. Even if he has to die in an ensuing shootout, he’s done his paternal duty for his flesh and blood. One must question what the bloodshed accomplishes. In this film, it’s a fitting end of fatalism. Whether it could have been avoided is quite another matter.

3.5/5 Stars

Note: This review was written before the passing of Kirk Douglas on February 5th, 2020.

Julie London provides her airy voice to the title track and Elmer Bernstein gives his scoring talents for the rest of the picture. In these beginning moments, Saddle the Wind evokes the expanse of the majestic landscapes of the West like the best of its brethren. There is a sense we really are out on the frontier, not some manufactured piece of artifice. For the time being, the film maintains this sense of the wind-open spaces away from Hollywood soundstages.

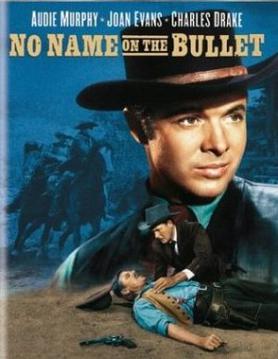

Julie London provides her airy voice to the title track and Elmer Bernstein gives his scoring talents for the rest of the picture. In these beginning moments, Saddle the Wind evokes the expanse of the majestic landscapes of the West like the best of its brethren. There is a sense we really are out on the frontier, not some manufactured piece of artifice. For the time being, the film maintains this sense of the wind-open spaces away from Hollywood soundstages. “We might be the only two honest men in town.” – Audie Murphy as John Gant

“We might be the only two honest men in town.” – Audie Murphy as John Gant There are few better ways to get yourself into the spirit of a western than the majestic gusto of Frankie Laine (self-parodied in hilarious fashion by Blazing Saddles). It’s the segue into a mythical world.

There are few better ways to get yourself into the spirit of a western than the majestic gusto of Frankie Laine (self-parodied in hilarious fashion by Blazing Saddles). It’s the segue into a mythical world.

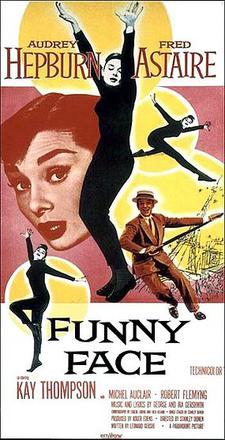

I’m not an expert on fashion photographers, but with only a passing interest in the industry, two of the most luminous names I know are probably Richard Avedon and Bob Willougby. Their names seem to crop up more than almost anyone when you consider film stills. It’s no coincidence that they both famously did shoots of Audrey Hepburn: one of the most widely photographed women of all time.

I’m not an expert on fashion photographers, but with only a passing interest in the industry, two of the most luminous names I know are probably Richard Avedon and Bob Willougby. Their names seem to crop up more than almost anyone when you consider film stills. It’s no coincidence that they both famously did shoots of Audrey Hepburn: one of the most widely photographed women of all time.