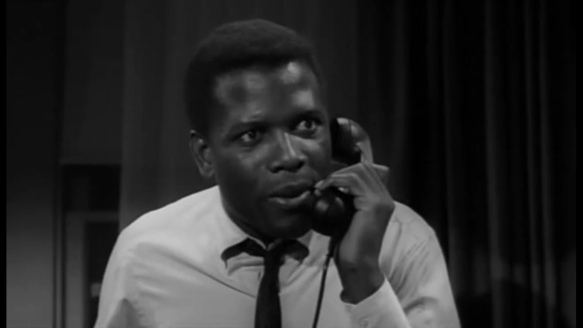

In honor of the inimitable Sidney Poitier, I spent some time revisiting a bevy of his finest films and also some underrated ones that were new to me. Because he was a prominent archetype for a black movie star, when he was often the only one, it’s fascinating to see the roles he chose at different junctures in his career and how they evolved and played with his well-remembered screen image.

He will be dearly missed, but he left a sterling career behind well worth our consideration. Here are three films you may not have seen before:

For Love of Ivy (1968)

As best as I can describe it, For Love of Ivy, features Poitier and Abbey Lincoln in their version of a Doris Day and Rock Hudson rom-com. It starts out a bit cringy. Lincoln is the maid of the most hopelessly oblivious white family. Mom and Dad are completely blindsided when she says she wants to quit so she can actually have a life with prospects.

Instead of listening to her, the two teen kids ( a hippy Bea Bridges and bodacious Lauri Peters) scheme to set her up with an eligible black man. They know so few, but Tim Austin (Bridges) settles on Jack Parks, a trucking executive because he conveniently has some leverage to get Jack to give Ivy a night on the town. Some awkward matchmaking (and blackmail) ensues to bring our couple together.

Hence how Lincoln and Poitier become an item. But even this dynamic has some unprecedented delights. They eat Japanese food together and visit a club that positively scintillates with ’60s vibes as seen through Hollywood’s eyes. It’s the age-old ploy where the transactional relationship morphs into real love until the truth threatens to ruin the romance. Again, it’s not exactly new hat from Robert Alan Arthur.

Still, with a happy ending and equilibrium restored, Poitier, who helped develop the story, is trusting his audience can read between the lines of all the dorky craziness. For what it is, the movie plays as a great showcase for Poitier and Lincoln. Since there are so very few movies like this with black leads, it feels like a cultural curio. If the mood strikes you, some might even find a great deal more agreeable than Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner because it doesn’t take its own social importance too seriously. It’s mostly wacky fun.

3.5/5 Stars

The Lost Man (1969)

The Lost Man features an edgier more militant Poitier because there’s no doubt the world around him had changed since he first got to Hollywood in the ’50s. He’s cool, hidden behind his shades, and observing the very same world with tacit interest. It’s a world ruled by social unrest as his black brothers and sisters picket and protest the racial injustices around them only to be forcibly removed by the authorities.

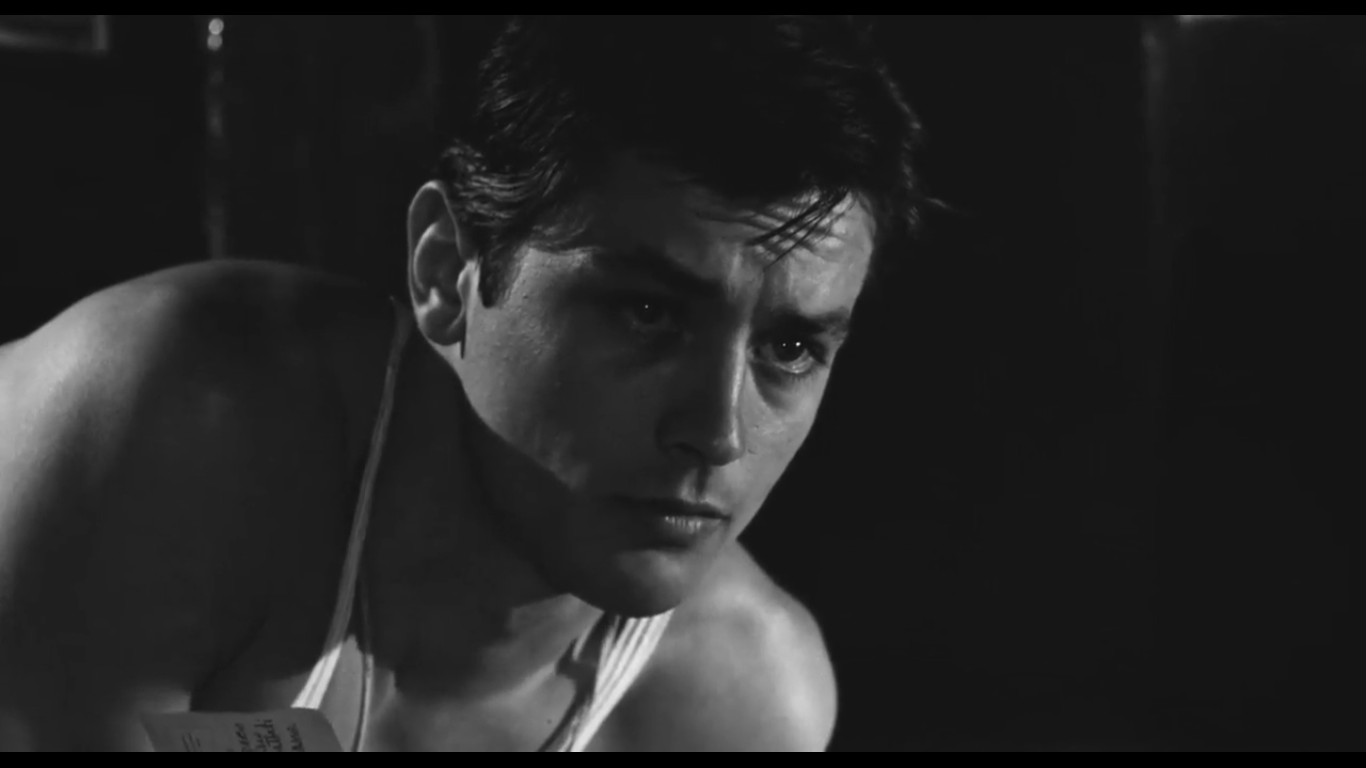

Robert Alan Arthur’s film shows a brief focused snapshot of the social anxieties of the age. It becomes more convoluted when Jason and some other members of the organization rob a local bank. Their motives are in some ways philanthropic as they hope to use the funds to get some of their friends out of prison and support their families on the outside. But it’s also an overt act of insurrection in their battle against a broken system.

It also puts lives in jeopardy, culminating in a frantic murder as the police hunt for the perpetrators in the botched aftermath. Jason flinches in a crucial moment and must spend the rest of the movie as a fugitive nursing a bullet wound. These all feel like typical consequences in a crime picture circa 1969.

However, one of the most crucial and fascinating relationships in the movie is between Joanna Shimkus, who is a social worker, and Poitier. We don’t get too much context with them, but it’s an onscreen romance that would predate their marriage in real-life. Their rapport complicates the story because she is a white woman who is so invested in this community like few people are, and she effectively brings out a gentler more intimate side of him.

Although it’s not necessarily pushed on us, their interracial romance puts them both in jeopardy because it’s not the way the world normally operates. The ending somehow gave me brief flashbacks to Odd Man Out, but Poitier’s marriage with Shimkus would last well over 40 years! It’s the best denouement this movie could ever hope to have.

3/5 Stars

Brother John (1971)

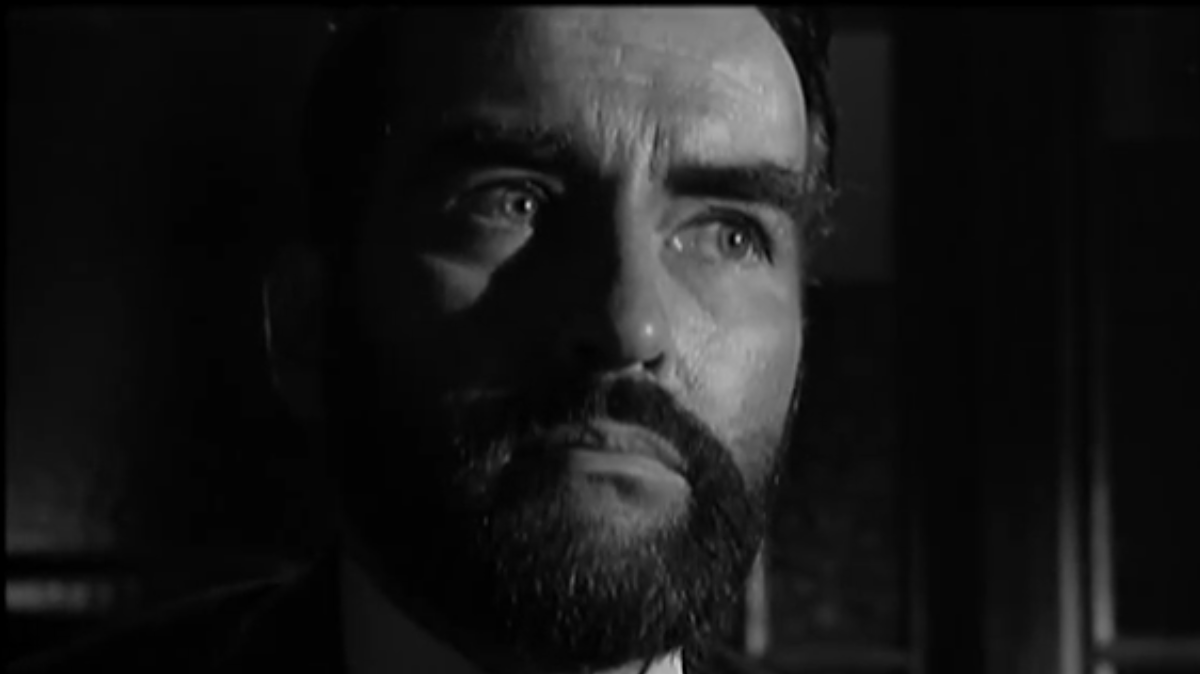

Brother John feels like one of those characters who is a cinematic creation. He joins James Stewart’s Elwood P. Dowd and anyone else who was ever sprinkled with something special that enchants the world around them, whether they’re angelic or extra-terrestrial. But Brother John is a different version for a different generation, and he’s played by none other than Sidney Poitier.

He provides a quiet catharsis for a black audience as a cipher of a man that no one can get a read on. The film itself has a no-frills TV movie aesthetic that somehow still gels with its ambitions.

John comes back to town when he gets news of his sister’s death. The last time he came back was when there was another death in the family. The local doctor (Will Geer), who brought John into the world, is curious about where he comes from and where he goes, but no one takes the old man too seriously.

Still, the police manage to hound him because they’re suspicious of someone they cannot easily intimidate and put in a box. The doctor’s self-promoting son (Bradford Dillman) also needles him in his attempt to gain local prominence. The town’s leaders are looking to quell a factory from unionizing. All of this feels rather mundane in detail. John seems to have nothing to do with any of it.

They remain uncomfortable with him because he’s so inscrutable, well-traveled, knows a myriad of languages, and finds no need to divulge all the shades of his character. He’s contented this way, spending time with family and even calling on a pretty schoolteacher (Beverly Todd) who asks for his company. He won’t play by their preordained script.

There’s one painfully excruciating scene where some cops pay a house call on a black family. The man of the house is left so powerless as he’s subjugated and persecuted in his own home in front of his kids. John is at the table too. Quiet at first. Almost emotionless. Is he just going to sit there or spur himself into action?

In this uncanny moment, he goes down to the basement with one of the officers and proceeds to whoop the tyrant wordlessly with a bevy of skills the backwater lawmen could never dream of. It’s the kind of power exerted over malevolent authority that one could only imagine in your wildest dreams.

As such, Brother John fits in somewhere analogous to the Blaxploitation space but as only Poitier could do it. He wasn’t the same bombastic militant cool dude a generation craved for and received in Shaft or Superfly. He still has his measured exterior, and yet he equally makes quick work of any antagonists: racists, malcontents, white, black, or otherwise. It’s a bit of a boyish fantasy watching a hero vanquish all evildoers quite spectacularly. But, after all, this is what movies are for.

3/5 Stars