You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams.

You couldn’t hope to come up with a better story than this. Pure movie fodder if there ever was and the most astounding thing is that it was essentially fact — spawned from a William Goldman script tirelessly culled from testimonials and the eponymous source material. All the President’s Men opens at the Watergate Hotel, where the most cataclysmic scandal of all time begins to split at the seams.

And Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) joined by Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) were right there ready to pursue the story when nobody else wanted to touch it. The Washington Post went out on a limb when no other paper would. Because if we look at the historical climate, such an event seemed absolutely ludicrous. Richard M. Nixon was the incumbent president. Detente had led to cooled tensions with the Soviets. And Democratic nominee George McGovern looked to be on a self-destructive path.

But the facts remained that these “burglars” had ties to the Republican Party and potentially the White House. It was tasked to Woodward and Bernstein to figure out how far up the trail led. And to their credit the old vets took stock in them — men made compelling by a trio of indelible character actors Martin Balsam, Jack Warden, and Jason Robards.

Woodward begins hitting the phones covering his notepad with shorthand and chicken scratch, a web of names and numbers. With every phone call, it feels like they’re stabbing in the dark, but the facts just don’t line up and their systematic gathering of leads churns up some interesting discoveries. Names like Howard Hunt, Charles Colson, Dardis, Kenneth H. Dahlberg all become pieces in this patchwork quilt of conspiracy. The credo of the film becoming the enigmatic Deep Throat’s advice to “Follow the money” and so they begin canvassing the streets encountering a lot of closed doors, in both the literal and metaphorical sense.

But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces.

But it only takes a few breakthroughs to make the story stick. The first comes from a reticent bookkeeper (Jane Alexander) and like so many others she’s conflicted, but she’s finally willing to divulge a few valuable pieces of information. And as cryptic as everything is, Woodward and Bernstein use their investigative chops to pick up the pieces.

Treasurer Hugh Sloan (Stephen Collins) stepped down from his post in the committee to re-elect the president based on his conscience, and his disclosures help the pair connect hundreds of thousands of dollars to the second most powerful man in the nation, John Mitchell. That’s the kicker.

It’s hard to forget the political intrigue the first time you see the film. What I didn’t remember was just how open-ended the story feels even with the final epilogue transcribed on the typewriter. The resolution that we expect is not given to us and there’s something innately powerful in that choice.

Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact.

Gordon Willis’s work behind the camera adds a great amount of depth to crucial scenes most notably when Woodward enters his fateful phone conversation with Kenneth H. Dahlberg. All he’s doing is talking on the telephone, but in a shot rather like an inverse of his famed Godfather opening, Willis uses one long zoom shot — slow and methodical — to highlight the build-up of the sequence. It’s hardly noticeable, but it only helps to heighten the impact.

Furthermore, some dizzying aerial shots floating over the D.C. skyline are paired with Redford and Hoffman’s voice-over as they are canvassing the streets to convey the type of paranoia that we would expect from a Pakula film. Because, much like the Parallax View before it, All the President’s Men holds a wariness towards government, and rightfully so. However, there is a subtext to this story that can easily go unnoticed.

The name Charles Colson is thrown around several times as a special counselor to the president, and Colson like many of his compatriots served a prison sentence. That’s not altogether extraordinary. It’s the fact that Chuck Colson would become a true champion of prison reform in his subsequent years as a born-again Christian, who was completely transformed by his experience in incarceration. And he did something about it starting Prison Fellowship, now present in over 120 countries worldwide.

It reflects something about our nation. When the most corrupt and power-hungry from the highest echelons of society are brought low, there’s still hope for redemption. Yes, our country was forever scarred by the memory of Watergate, but one of the president’s men turned that dark blot into something worth rooting for. It’s exactly the type of ending we want.

4.5/5 Stars

Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people.

Two hallmarks of the political film genre are Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and All the President’s Men. The latter starred The Candidate’s lead, Robert Redford. However, in this case, the candidate, Billy McKay, is perhaps a more tempered version of Jefferson Smith. He’s a young lawyer, good looking and passionate about justice and doing right by the people. It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on.

It’s the bane of my literary existence, but I must admit that I have never read Joseph Heller’s seminal novel Catch-22. Please refrain from berating me right now, perhaps deservedly so, because at least I have acknowledged my ignorance. True, I can only take Mike Nichol’s adaptation at face value, but given this film, that still seems worthwhile. I’m not condoning my own failures, but this satirical anti-war film does have two feet to stand on. The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat.

The Chaplain (Anthony Perkins) doesn’t feel like a man of the cloth at all, but a nervously subservient trying to carry out his duties. An agitated laundry officer (Bob Newhart) gets arbitrarily promoted to Squadron Commander, and he ducks out whenever duty calls. Finally, the Chief Surgeon (Jack Gilford) has no power to get Yossarian sent home because as he explains, Yossarian “would be crazy to fly more missions and sane if he didn’t, but if he was sane he’d have to fly them. If he flew them he was crazy and didn’t have to; but if he didn’t, he was sane and had to.” This is the mind-bending logic at the core of Catch-22, and it continues to manifest itself over and over again until it is simply too much. It’s a vicious cycle you can never beat. But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale.

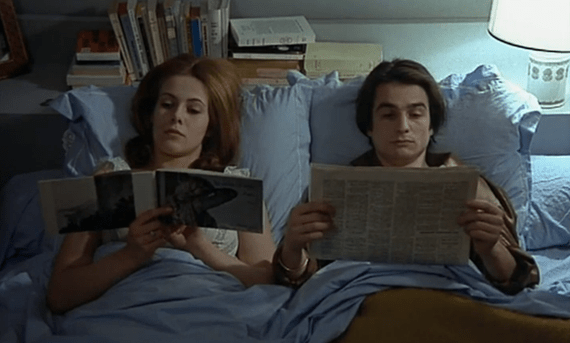

But the tonal shift of Catch-22 is important to note because while it can remain absurdly funny for some time, there is a point of no return. Yossarian constantly relives the moments he watched his young comrade die, and Nately (Art Garfunkel) ends up being killed by his own side. It’s a haunting turn and by the second half, the film is almost hollow. But we are left with one giant aerial shot that quickly pulls away from a flailing Yossarian as he tries to feebly escape this insanity in a flimsy lifeboat headed for Sweden. It’s the final exclamation point in this farcical tale. Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain.

Arguably the greatest French comic was Jacques Tati and like Chaplin or Keaton he seemed to have an impeccable handle on physical comedy, combining the human body with the visual landscape to develop truly wonderful bits of humor. Bed and Board is a hardly a comparable film, but it pays some homage to the likes of Mon Oncle and Playtime. There’s a Hulot doppelganger at the train station, while Antoine also ends up getting hired by an American Hydraulics company led by a loud-mouthed American (Billy Kearns) who closely resembles one of Hulot’s pals from Playtime. Furthermore, there are supporting cast members with a plethora of comic quirks. The man who won’t leave his second story apartment until Petain is dead and buried at Verdun. No one seems to have told him that the old warhorse has been dead nearly 20 years. The couple next door that is constantly running late, the husband pacing in the hallway as his wife rushes to make it to his opera in time. There’s the local strangler who is kept at arm’s length until the locals learn something about him. The rest is a smattering of characters who pop up here and there at no particular moment. Their purpose is anyone’s guess, and yet they certainly do entertain. But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns.

But as Truffaut usually does, he digs into his character’s flaws that suspiciously look like they might be his own. Antoine easily gets swayed by the demure attractiveness of a Japanese beauty (Hiroko Berghauer), and he begins spending more time with her. Thus the marital turbulence sets in thanks in part to Antoine’s needless infidelity –revealed to Christine through a troubling bouquet of flowers. It’s hard to keep up pretenses when the parent’s come over again and Doinel even ends up calling on a prostitute one more. It’s as if he always reverts back to the same self-destructive habits. He never quite learns. The Marriage of Maria Braun opens with a bang and a thud, literally, as bombs rain down on Germany in the waning hours of WWII. It’s perhaps the most chaotic wedding ceremony ever put to celluloid. And the story ends in an equally theatrical fashion.

The Marriage of Maria Braun opens with a bang and a thud, literally, as bombs rain down on Germany in the waning hours of WWII. It’s perhaps the most chaotic wedding ceremony ever put to celluloid. And the story ends in an equally theatrical fashion. It’s hardly Charles Dickens, but still, Hard Times is a real tooth and claw street brawler. We have Charles Bronson as our token taciturn drifter, tough and down on his luck during the Depression. James Coburn is Speed, a fast-talking promoter looking for a quick buck. Walter Hill’s film may not be pretty to look at, but boy is it a lot of fun! Everyone’s favorite supporting scene stealer Strother Martin makes an appearance as a sometime doctor who dropped out of med school. These three men are at the center of an evolving partnership that comes into being on the streets of New Orleans, that hopping town of jazz, juke joints, and bare-knuckle boxing. The latter is the most important for the men aforementioned because, with Speed as his manager and Poe as his ringside doc, Chaney looks to rule the ocean front with his grit and tenacity.

It’s hardly Charles Dickens, but still, Hard Times is a real tooth and claw street brawler. We have Charles Bronson as our token taciturn drifter, tough and down on his luck during the Depression. James Coburn is Speed, a fast-talking promoter looking for a quick buck. Walter Hill’s film may not be pretty to look at, but boy is it a lot of fun! Everyone’s favorite supporting scene stealer Strother Martin makes an appearance as a sometime doctor who dropped out of med school. These three men are at the center of an evolving partnership that comes into being on the streets of New Orleans, that hopping town of jazz, juke joints, and bare-knuckle boxing. The latter is the most important for the men aforementioned because, with Speed as his manager and Poe as his ringside doc, Chaney looks to rule the ocean front with his grit and tenacity. Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble holds a meta quality that still somehow feels radically different than Godard or Truffaut’s turns in Contempt and Day for Night. It attempts to channel a younger point of view — that of an ambitious student — with an overtly political agenda. Agnieszka is an independent, fiery individual intent on making her thesis the way she sees fit. She’s prepared to go digging around in uncharted territory or at least in territory that has been off limits for a long time. That understandably unnerves her adviser and still, she forges on.

Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble holds a meta quality that still somehow feels radically different than Godard or Truffaut’s turns in Contempt and Day for Night. It attempts to channel a younger point of view — that of an ambitious student — with an overtly political agenda. Agnieszka is an independent, fiery individual intent on making her thesis the way she sees fit. She’s prepared to go digging around in uncharted territory or at least in territory that has been off limits for a long time. That understandably unnerves her adviser and still, she forges on. Everywhere she goes Agnieszka drags along her crew who utilize handheld cameras and wide-angle lenses, at her behest, just like American films. It becomes obvious that Birkut was hardly a political figure, instead contenting himself by using his hands to lay breaks and lay them well. He takes pleasure in his work with a big sloppy grin almost always plastered on his face. It was people like him who made Nowa Huta into the great city of industry that it was, and he became an emblem of that. The party monumentalized him and he became the man of marble to be lauded by all.

Everywhere she goes Agnieszka drags along her crew who utilize handheld cameras and wide-angle lenses, at her behest, just like American films. It becomes obvious that Birkut was hardly a political figure, instead contenting himself by using his hands to lay breaks and lay them well. He takes pleasure in his work with a big sloppy grin almost always plastered on his face. It was people like him who made Nowa Huta into the great city of industry that it was, and he became an emblem of that. The party monumentalized him and he became the man of marble to be lauded by all. You can take Animal House one of two ways. Either it glorifies fraternity life to chaotic proportions or it’s a satirical mockery of the collegiate institutions. Either way, the film works, because the bottom line is that it has laughs. Sure, some of them take hold of nostalgia while simultaneous instigating the trend towards crude, gross-out humor, but Animal House has some generally uproarious moments of mayhem to match some quality pieces of irony. When you actually think about it a lot of these characters are great fun too.

You can take Animal House one of two ways. Either it glorifies fraternity life to chaotic proportions or it’s a satirical mockery of the collegiate institutions. Either way, the film works, because the bottom line is that it has laughs. Sure, some of them take hold of nostalgia while simultaneous instigating the trend towards crude, gross-out humor, but Animal House has some generally uproarious moments of mayhem to match some quality pieces of irony. When you actually think about it a lot of these characters are great fun too.