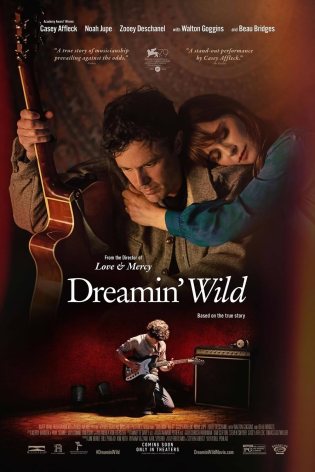

I’m a sucker for a good jukebox biopic and Dreamin’ Wild is one of the films that might fly under the radar just like its subjects. And yet when you actually come face to face with it you find something tender and sentimental in the most endearing of ways.

I’m a sucker for a good jukebox biopic and Dreamin’ Wild is one of the films that might fly under the radar just like its subjects. And yet when you actually come face to face with it you find something tender and sentimental in the most endearing of ways.

There’s something to be said of a contemporary movie that unabashedly focuses on a close-knit family that loves each other dearly and celebrates them. For whatever reason, contemporary cinematic culture almost feels averse to certain topics because they feel staid and formulaic. Subversion and cynicism win the day on most occasions.

Dreamin’ Wild almost feels radical because the film is buoyed by so much goodness and it’s part of what makes this adaptation of the Emerson brothers’ story worth felling. The fact that these teenagers made music, and it only made a dent 30 years after its release is astounding. In the same breath, it feels like something worth championing without a lot of fabricated drama — at least in the beginning.

The ascension and the celebration of the success in itself is the kind of underdog story that still can grip us as human beings. Dreamin’ Wild reminds us why. Matt Sullivan (Chris Messina) has been trying to find them because he wants to reissue their work on his record label. There’s a sincerity to him that’s disarming and genial. You can tell he’s genuinely glad to be brought into this family’s orbit and do this for them.

Donnie (Casey Affleck) and Joe (Walton Goggins) find out the internet is blowing up about their record. Pitchfork gives them a fantastic review and The New York Times comes out to do a profile on the family. Matt says there’s high demand for some concerts to get them out there in front of fans. The upward trajectory is rapid and yet so thrilling to watch unfold because we get to live vicariously through the brothers’ joy deferred after so many years.

In the face of this overnight stardom, Affleck does his trademark mopey, despondent role, but in all fairness, he does it quite well. We wonder what it is buried in his past that might conceivably get in the way, but it’s a story engaged with the artist and the creative genius coming up against familial obligation. And in this regard, it seems pertinent to highlight the movie’s writer and director.

Bill Pohlad’s other most prominent project as a director was Love & Mercy about Brian Wilson, and it’s easy enough to try and thread these stories together. They share similar architecture with two contrasting timelines. This one throws us back into Donnie and Joe’s boyhood with small swatches of time and interactions reverberating into the present.

You begin to see what might have drawn the writer-director to this pair of stories because they examine someone with such an uncompromising creative vision, but for whatever reason this single-mindedness can somehow derail the relationships you hold most dear. Things around you suffer for the sake of the art.

And whereas Brian was struggling against his own demons and the authoritarian presence of his father, Dreamin’ Wild almost has the answer to that. Donnie’s father as played so compassionately by Beau Bridges is the picture of generosity and unconditional love. So much so it almost crushes Donnie with his own guilt and shame — the inadequacies he feels with his failed music career thus far. He’s dealing with some issues analogous to Brian in some ways, but they develop in a very different kind of creative environment.

Joe (Goggins) is such a pleasant person and it becomes evident he’s always been a champion for Donnie, his creativity and his talent. They’re close-knit and always ready to support one another. And Joe knows he’s not going to be some great artist and he’s contented in that; Joe takes each new develop with a wonder and genuine appreciation. He’s pretty much happy to be along for the ride, but he’s present through it all. His younger brother struggles to do the same because he’s terrified about making the most of his opportunity and with it comes debilitating angst.

In a movie enveloped and incubated in so much goodness, it’s ultimately this that threatens to derail the whole uplifting narrative. One crucial scene involves the rehearsal process. Joe is just getting back into it. He’s rusty, and so to compensate Donnie brings in some back up musicians including his talented wife Nancy (Zooey Deschanel).

Donnie’s tormented perfectionism will not condone his brother’s mediocre playing and so he lashes out. It’s true maybe he’s not John Bonham, but something has been lost and the magic of the moment is in danger of evaporating amid this kind of creative tyranny.

Joe feels awkward; he can’t defend himself and so Nancy stands up for him and calls out her husband for his distorted expectations. What is this big triumphal success, this grand rediscovery if Donnie cannot enjoy it with his brother playing drums by his side? It would feel hollow any other way. Those of us who are not musical savants understand intuitively.

It’s about being present and appreciating the moment. Sometimes less than perfect is okay if it means getting the most out of what’s in front of you and being fully present with the people you love. Because what does perfection profit you? We always fall short. Still, if you have family in your corner who know and love you in spite of your faults, that is a supreme a gift.

The movie’s most fundamental themes are about brothers, fathers and sons, and so more that I resonate with. I won’t try to put words to them all so that you might be able to experience them of your own accord. Even a momentary prayer before a big show feels emblematic of a quiet revolution.

Ultimately the boys do reconcile and they have one final performance. It’s not a big triumphant show (like before), and although I enjoyed hearing the music again I questioned the necessity of the moment.

Then Pohlad did something I wasn’t expecting; it took my breath away. He shows his two actors. They’re on guitar, drums, and singing. The audience, including their parents, looks on, and then when he cuts back. Now staring back at us are the real Emerson brothers in the flesh.

I can’t quite articulate it, but there’s something so powerful about this subtle shift as the make-believe of the movies becomes reality, and we see those people there making music together and enjoying one another’s company with their real parents looking on. It’s a full-circle culmination of everything we could desire.

I think it’s the intimacy I appreciate it. You can tell the people making this movie — just like Chris Messina’s character — are doing it because they are captivated by this story. It moves them. I feel the same way, and for whatever the flaws or tropes of Dreamin’ Wild, I was immediately rooting for it. Of course, the first thing I did after the credits rolled was to search out this little record from 1979 by two rural teenagers. Pretty remarkable.

3.5/5 Stars

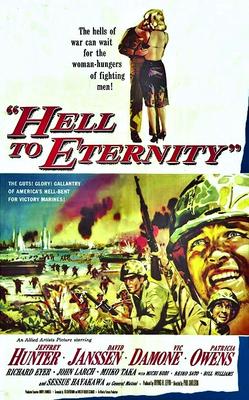

As someone of Japanese-American heritage, it’s become a personal preoccupation of mine to search out films that in some way represent the lives of my grandparents and their generation. This means the rich Issei and Nisei communities of Los Angeles, the subsequent internment camps, and even the famed 442nd Infantry Battalion.

As someone of Japanese-American heritage, it’s become a personal preoccupation of mine to search out films that in some way represent the lives of my grandparents and their generation. This means the rich Issei and Nisei communities of Los Angeles, the subsequent internment camps, and even the famed 442nd Infantry Battalion.

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.

I Want to Live! calls upon the words of two men of repute to make an ethos appeal to the audience. The first quotation is plucked from Albert Camus. I’m not sure what the context actually was but the excerpt reads, “What good are films if they do not make us face the realities of our time.” This is followed up by some very official-looking script signed by Edward S. Montgomery, Pulitzer Prize winner, who confirms this is a factual story based on his own journalism and the personal letters of one Barbara Graham.