The film version of Kiss Me Kate, helmed by MGM’s perennial musical director George Sidney, is a translation of Cole Porter’s rousing Broadway success. We must play a game of two degrees of separation because the stage smash was itself a comical backstage adaptation of Shakespeare’s Taming of The Shrew. I cannot necessarily attest to where one begins and the other ends, between stage, film, and original play, since my own knowledge is shoddy at best. So I will contain my thoughts to the story at hand.

At its core are the strained relations of a formerly married couple composed of two prima donna stage performers: the devilishly handsome, barrel-chested baritone Fred Graham (Howard Keel) and his equally strong-willed, alluring, and talented ex Lilli Vanessi (Kathryn Grayson). In all regards, a match made it heaven. They undoubtedly deserve each other.

The undisputed peppiness of Ann Miller, as she bursts in on them and Cole Porter (Ron Randell), is an immediate jovial assault on their relationship as she flaunts her attributes in “Too Darn Hot” and gets a little lovey-dovey with the self-absorbed leading man. I’m not sure if any audience member is shocked when she’s seen playfully prancing about with her other boyfriend (the always impressive Tommy Rall) in “Why Can’t You Behave?”

To needlessly mix metaphors, the production is nearly sunk before it gets off the ground. And yet a mixture of persuasion, jealousy, and the quality of the material coaxes Grayson’s character into the fragile reunion. Wunderbar!

Lilli’s rendition of “I Hate Men” proves a blatantly pointed number where on stage sentiments are mirrored in her life; she doesn’t mince words raging through the set, flinging props to her obvious satisfaction.

In fact, she’s far more suited for the flaming red wig she wears on stage than her actual modest cut. The 3-D qualities come to bear thanks to the tossing of beer steins and flower bouquets. It’s one of visual cues to suggest this very purposeful sense of the off-stage and on-stage lives merging and colliding with one another.

We have the backroom interludes and then the continuous sequences of the performance photographed straight on until little discrepancies come into play to make everything run afoul.

Breaks in characters. Personal vendettas playing out on stage with each minor slap and smack in the stage directions supplied with ample fury from years of pent-up rage. Deviations in the actual production also come to pass. Namely, a cringe-worthy spanking as the midway curtain drops.

It’s in the intermittent period where Kate utters that immortal Shakespearian retort, “Thou Jerk.” In fact, there’s great fun to be had with this conscious collision of Old English prose and the contemporary vernacular. The number “Brush Up On Your Shakespeare” suggests as much.

Keenan Wynn and James Whitemore are brought on to thoroughly liven up the second act as a pair of neighborly enforcers sent to visit Fred in his dressing room. They go so far as becoming a part of the production as it continues to go off script and off-the-rails. Because Kate is intent on running off with her rich boyfriend Tex (a Ralph Bellamy-type), and Graham connives to keep her around, pulling the heavies into his plan.

It feels strikingly like a His Girl Friday (1940) deal as we see our leads gravitating toward others while never finding it within themselves to completely forsake their former spouses, in spite of the mutual distaste. It’s indisputable, but it also suggest the fire still kindling between them.

Hermes Pan adds to his illustrious body of work while Bob Fosse’s choreography is almost a blip on the radar. Even then, it’s strangely singular and expressive, charting his course toward The Pajama Game and many, many more projects to come.

Meanwhile, Ann Miller’s dancing reminds us that she’s the purest performer on taps within this picture and when given free-range, she follows up her first routine with continued verve. She does feel all over the place, but that can mostly be attributed to her character. In fact, one could affirm that she rightfully earns some of the most memorable screen time based on the uninhibited vivacity she showcases.

In its waning moments, it looks like the fictional production has finally met its inevitable end: a crash-and-burn finale, as the understudy has to rush on to take the place of the departing Catherine. In an off-the-cuff moment, playing opposite his future father-in-law’s question of where his daughter might possibly be, Fred mutters, “Right now she should be flying over Newark.”

Thus, Kiss Me Kate, at its most inventive, is hyper-aware of its meta qualities; this story-within-a-story tracing the line between the artificial and the reality projected up on the screen that is itself a fabrication of light and images. It reaches out further than most films of this type because its original release in 3-D, while admittedly a gimmick to snag the TV generation, also accentuates this razor-thin dividing line between the cinematic space and the space that the viewer occupies.

However, ultimately the production though laced with humor and vengeful lovers, quality choreography, and flamboyant set design and costuming, comes off strangely hollow in its landing. Because the ending feels false and inherently wrong.

Here is a man who is conceited and has no sense of self-sacrifice or concern for others, as farcical as he might be. Again, we could argue that Kiss Me Kate is solely entertainment, only occupying cinematic space. And yet we brushed up against everything thus far. How are we to make distinctions? In the real world, even in the 1950s and especially now, there is no excuse for Graham.

Surely, like any person, he deserves a second chance and the grace that comes from a person willing to forgive. However, one might question the way in which Lilli flies back to him. There seems to be no regard for his past indiscretions just as there’s no conversation to be had about the flings they’ve both been having on the sides. Because Kate is herself a bit of an entitled snob. And there you have this falseness most fully realized.

Life is a lot more complicated than film reality. Kiss Me Kate cannot quite pull it off because it inserts the uncluttered, picture-perfect Hollywood framing on the storyline.

Ironically, it’s actually the performance that gets continually disrupted while so-called real-life falls into place nearly seamlessly. So in the end, it matters whether you care about making a distinction between the stage and what happens backstage in the purported reality.

Because at least we can all agree that none of it is actually before us in the flesh where real lives are at stake. We can keep it at an arm’s length and laugh along with it without allowing it to influence our perceptions of this world.

Taken as such, Kiss Me Kate is a coruscating delight bursting forth, rather agreeably, with comedy and song. It can be absorbed merely as diverting Technicolor entertainment for sure. However, when we allow it to reach out and influence our worldview in other ways that’s where we might falter.

3.5/5 Stars

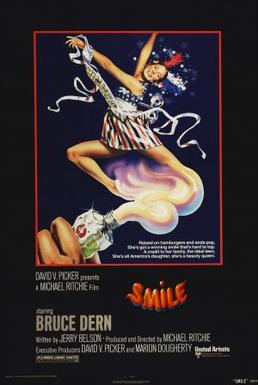

“Smile” is a timeless hit among a plethora of classic Nat King Cole tracks. The innate warmth and the soothing nature of his vocals shine through every note. It took me many years to realize the tune was actually a Charlie Chaplin composition from

“Smile” is a timeless hit among a plethora of classic Nat King Cole tracks. The innate warmth and the soothing nature of his vocals shine through every note. It took me many years to realize the tune was actually a Charlie Chaplin composition from

I never thought I’d be saying this about a Woody Allen film, but it feels more like a technical marvel than purely a testament to story or dialogue. Although

I never thought I’d be saying this about a Woody Allen film, but it feels more like a technical marvel than purely a testament to story or dialogue. Although