Back to the Future is a film I have deep reservoirs of affection for, and I know it’s far from a landmark statement — I’m hardly in the minority. However, I will say that as I began to watch Peggy Sue Got Married, I slowly became attuned to its world and the unfolding premise. There seemed to be some very basic similarities.

Back to the Future is a film I have deep reservoirs of affection for, and I know it’s far from a landmark statement — I’m hardly in the minority. However, I will say that as I began to watch Peggy Sue Got Married, I slowly became attuned to its world and the unfolding premise. There seemed to be some very basic similarities.

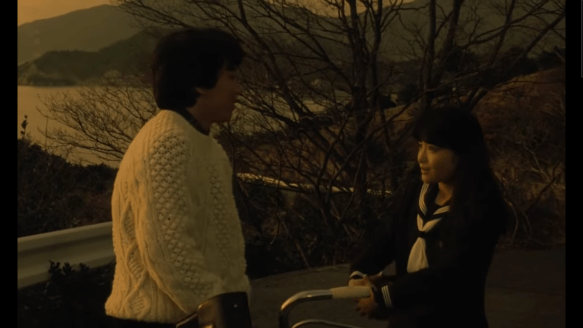

Peggy Sue (Kathleen Turner) attends her 25th high school reunion with her daughter (Helen Hunt), reconnecting with old friends even as she rues her relationship with her husband and high school sweetheart (Nicolas Cage). She’s christened the evening’s queen of the class and faints from the excitement. As she drifts away, she wakes up, and it’s 1960 again. No DeLorean or Libyan terrorist necessary. She opens her eyes, and she’s there.

Jerry Leichtling and Arlene Sarner’s screenplay utilizes some of the same time-tested tropes from Back to the Future, like uncanny knowledge that feels sentient to those living in the past, even as it’s common knowledge to those in the future, be it the Moon landing or pantyhose (or Calvin Klein for that matter). These breed rampant cultural miscommunications — the kind you get in these fish-out-of-water stories — engendered by messing with time. Peggy even bemoans the fact that she’s a walking anachronism.

The beauty of the picture is how it becomes something else entirely as it gets beyond these cursory elements to bring us something different — a far more pensive meditation. It’s not bombastic with Zemeckis’s flair for Sci-Fi or Christopher Lloyd’s out-of-this-world performance as Doc Brown. There aren’t the same ticking clocks or steadily increasing stakes that Marty must race against to save his parents (and his entire family’s existence). It’s not about that.

Kathleen Turner’s Peggy also has a poise and foresight Marty McFly was never supposed to have. Yes, they both go from the future into the past, but what a difference their life of experience makes.

Even the mechanisms of the time travel itself feel less important and mostly immaterial. We get beyond them quite quickly to focus on something more. Peggy marvels at seeing her parents as they used to be, as she remembers them when she was younger, and cherishes reconnecting with her baby sister (Sofia Coppola) as time has yet to sour their relationship.

At school, her whole outlook is different, too. Yes, she’s not prepared to redo her academics in the classroom, but her values are more intrinsic, and her social outlook is much more sincere. She’s cast off the insecurity we all have at that age to see the landscape with much greater lucidity.

She befriends the outcasts (one’s a nerd and a future billionaire); it’s not because she wants to capitalize on his future success, but because she knows he will believe her crazy reality. The other is a free spirit who scoffs at the literature they’re inculcated with in textbooks, instead nourishing himself on the self-expression of Jack Kerouac. It’s creative fodder for his own poetry as he seems to embody the dreams she never managed to pursue.

Also, she fosters an alternate relationship with her high school sweetheart: the man she married out of high school and ultimately divorced. She recognizes and even appreciates new contours to his character she was never prepared to notice before, just as she comes to forgive his flaws.

The casting as a whole might feel tighter than Back to the Future (which even famously included Michael J. Fox as an eleventh-hour replacement). There are so many faces who show up and give the right essence to the roles, whether it’s a young Jim Carrey, a very young Sofia Coppola, or Barbara Harris and Don Murray.

I will say, I’m not sure if Nic Cage’s characterization is to the benefit of the movie. His voice, his whining, almost petulant nature. He’s aged with makeup to near-comic proportions. And even this and his connection to the director (Coppola is his uncle) lend themselves to a kind of rapport. Because what is he supposed to be if not a mixed-up, angsty, regretful high schooler? Somehow, even this has less of the winking humor of Back to the Future. Miscast or not, it has an alternate level of sincerity.

And of course, there’s the instance when Peggy meets her grandparents. Leon Ames and Maureen O’Sullivan are impeccable. It’s such a pleasure to watch them because, being an Old Hollywood aficionado, they’ve been offered to me in so many films of yore. But the very rhythm of Peggy Sue visiting her grandparents is such a meaningful and cathartic one. It’s as if she’s somehow reclaiming these moments she always wished to have back, even as she willfully shares her out-of-body experience and gains a rapt and receptive audience in her elders.

In their eyes, she’s not crazy. It’s as if any skepticism has evaporated with time, and all that’s left over is a heavy dose of wonder and congeniality. True, I was a bit weirded out by her grandpa’s lodge, even as Bruce Dern’s secret society in Smile unnerved me. Here, it still manages to fit into the time travel narrative even as it lacks the level of import of Hill Valley’s clock tower. Again, that’s hardly the point.

When Peggy returns to her present, back to her daughter, her estranged husband, and everything else, whether through dreams or some other uncanny supernatural force, she has changed. This is what matters. It’s not butterfly effects or space-time continuums or quantum mechanics or anything like that. I can hardly speak to any of these. The movie speaks to what is universal: It’s the gift of getting to redirect your life, saying “I love you” to those you wish you had more time with, and reclaiming the mistakes gnawing at you. It feels like the most serendipitous type of science fiction.

When you have the likes of The Godfather, Apocalypse Now, or even The Conversation to your name, Peggy Sue Got Married is never going to enter into the conversation of Coppola’s best films. It’s mostly subdued and full of the joy and jubilation of a different time. But Coppola actually examines some fairly profound themes.

What’s more, although Kathleen Turner is mostly pigeonholed as a siren or a beauty, she’s quite good in a role that’s not flashy, and yet allows her to offer up a performance with subtle aplomb. It’s easy for these types of period movies (or movies from the ’80s in general) to feel like pastiche — mostly inane and made thoroughly for consumption. Even Back to the Future is ’80s Hollywood at its very best.

Here it feels like great care is being taken, and there’s a level of reflection and maturity that’s hard to discount. It’s saying something when we follow this woman through time and space, and we pretty much leave that device behind. What’s not lost is her emotional journey.

4/5 Stars